Drawing Parallels from History: Suez and Russia-Ukraine Crisis

On October 31, 1956, when Israel and the Anglo-French forces invaded Egypt during what came to be known as the Suez crisis, Jawaharlal Nehru said to J.F. Dulles, the then US Secretary of State, “If this aggression continues and succeeds, all faith in international commitments and the United Nations will fade away, and the old spectre of colonialism will haunt us again. This is a reversal of history which none of us can tolerate” (Gopal 1979). Even though Nehru’s India chose the path of non-alignment, the invasion of Egypt was not a matter where Nehru could withhold from taking sides. Contrary to what may seem obvious, Nehru’s decision was not a result of moral compulsions, but a well-thought-out stand based on national interest.

Similarly, Nehru’s position on the Hungary crisis that erupted during the same period cannot be termed ‘moral’ as well. On October 23, 1956, a student demonstration in Hungary led to the overthrow of the communist government, post which Soviet Russia on November 1 sent its troops to suppress the uprising and dethrone the popular government. Nehru’s condemnation of Israel during the Suez crisis and silence over USSR’s invasion of Hungary that same year reveals as to why India abstained from voting in the United Nations over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Although the nature of global politics has changed drastically between the times of Nehru and PM Narendra Modi, the ties between India and Russia (erstwhile USSR) have remained steadfast. At the heart of this friendship is defence cooperation. Russia has also supported India on its claim over the permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council and membership in the Nuclear Suppliers Group. Russia has been a trusted partner unlike the USA. As its critics argue, the USA is infamous for leaving its allies when needed. Though India gave in to the USA’s sanctions on Iran and stopped importing Iranian oil in 2019 which was 10% of the total India’s oil needs, it could not do the same in Russia’s case. Talking of India’s relations with the US-led western world, Prof. Harsh Pant said, “They know that there is only this much they can expect from India; they cannot push beyond a point.” Moreover, India has a history of staying away from issues concerning big powers. Therefore, India’s abstention reflects it taking sides not for anyone but itself. No wonder the opposition extended support to the Centre over the Ukraine crisis, saying, ‘we are all united’.

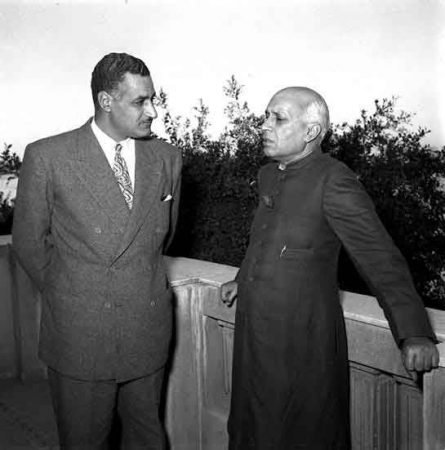

However, how India’s stance differs today, and where it can draw lessons from history, is that while both Nehru and Modi took sides, the former did not compromise on basic human rights. Even after the British tacitly accepted defeat in the Suez crisis and were ready to withdraw their forces, Gamal Abdel Nasser, the-then President of Egypt, did not stop there. He proposed deporting British, French, and nationals of Jewish origin from Egypt even though they did not conspire against Egypt during the war. It was revealed in the Indian chargé d’affaires’ interview with Nasser, dated December 5, 1956, that the reason behind said deportations had nothing to do with the war. Nasser believed that the British, French, and particularly the Jewish communities had dominated the Egyptian economy for decades, and now he found a reason to get rid of them.

Despite having sided with Egypt in the war for strategic reasons, Nehru raised his concern against deportation. “I would request you not to take steps which would compel a large number of persons to leave Egypt in penurious circumstances,” Nehru wrote to Nasser in a letter dated December 5, 1956, (Gopal 1979). In so doing, Nehru also fulfilled the promise he made to Albert Einstein, when he wrote to him, “As you know, national policies are unfortunately essentially selfish policies, but if we can help them [Jews] in any way, I hope and trust that India will not merely stand by and look on.”

The art of decision-making is often an exercise in drawing parallels from history and judging which parallel best suits a particular circumstance. As Nehru wrote in one of his letters to Indira Gandhi, “History never repeats itself exactly, and yet it is strange how near it comes to it sometimes” (Nehru 1934). Nehru’s India supported Egypt, the victim country, but also stood against human rights violations by the same country. On the other hand, Modi’s India neither lent diplomatic or militaristic support to Ukraine nor openly spoke about Russia’s use of violence against innocent civilians. Both the Prime Ministers took a call according to what seemed to them was in their nation’s best interest, and yet, their stances on interpreting laws of war are worlds apart.

Hence, the current regime can learn from the one under Nehru that one can remain resolute in evaluating national interests without compromising on the humanitarian principles that shape conduct of states parties to a war. Also given Modi’s strong personal relations with Vladimir Putin, India should try to leverage its ties with Russia to appeal for cessation of violence against civilians on humanitarian grounds. It is also critical to India’s global position as it may also help in not letting the western world get too offended by India’s stand on Russia-Ukraine crisis. Nehru’s vocalisation against the humanitarian crisis in Egypt won Winston Churchill’s praise, when he acknowledged Nehru’s assistance in appealing to Nasser in a telegram forwarded by British High Commissioner in Delhi on 1 July 1956. “Thank you so much for the help you gave us over Egypt and Israel,” the Telegram read (Gopal 1979). What makes Churchill’s gratitude to India significant is the fact that India opposed Britain throughout the Suez crisis, and yet united with them on a common humanitarian cause.

In a letter he wrote to the Indian ambassador in Cairo in 1956, Nehru said, “True wisdom consists in knowing how far we can go, to profit by the circumstances and to create a feeling of generosity which again results in a change in one’s own favour” (Gopal 1979). This perhaps best explains India’s strategic choices at the time and helps chart a trajectory for what kind of an approach the current regime can potentially deploy in the context of the Russia-Ukraine crisis.