Elephant ducking dragon

The rise of China, especially since 2013 when Xi Jinping assumed the rein of CCP, has rang alarm bells in policy corridors around the world and think tanks alike. Xi dumped Deng’s philosophy of “evading the limelight” and proclaimed the “arrival of China”. Since then, the world has witnessed an aggressive and a power-hungry China, hellbent on changing the post WWII world order. Xi’s China is heating to seek a new international order centred around Chinese power (1) As in thermodynamics, this heat has been “conducted” to China’s neighbors- India being at the forefront. India faces the burnt as China perceives it to be the only obstacle to its “hegemonic role in Eurasia”.

In a disordered world-where states are uncertain about their security, where partners are seen with cynicism and where balance of power is transforming rapidly, we must understand what China’s rise means for India? What are the challenges posed by Beijing and how Delhi has responded so far? How can India meet the challenges posed by China i.e elephant ducking dragon?

China’s accession, India’s recession

If we remove our hazy glasses, we see wherever China has entered a concomitant decline in India’s position is witnessed. The elephant has been too slow and weak in wake of the dragon’s offensive in its jungle.

South Asia, a region in which India enjoyed unquestioned hegemony after 1971, has shown signs of crack. Countries like Sri Lanka and Nepal have adopted an “antagonistic attitude” towards India. Bangladesh have made overtures and joined the BRI, strongly opposed by India. Bhutan is forced to negotiate border agreement with China by strategically embroiling India into a border conflict and thereby denying opportunity to India to come to Bhutan’s rescue, as in Doklam standoff. Taliban ruled Afghanistan, pampered by China and Pakistan, has squeezed the clout that India used to enjoy in Afghanistan. Along with South Asia, West Asia hasn’t also remained aloof from Chinese shadow.

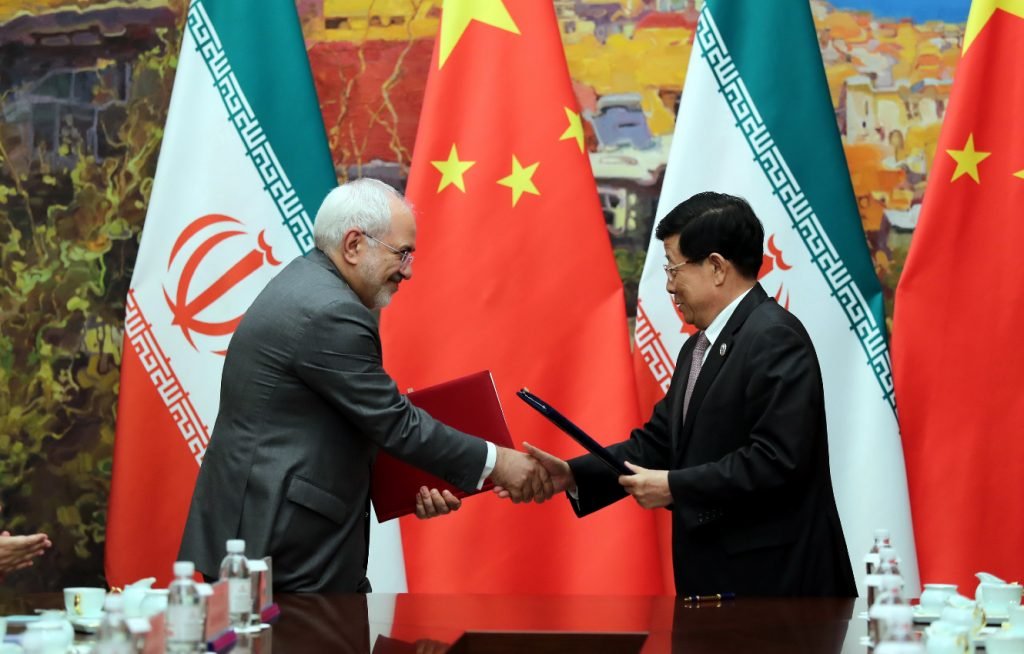

Chinese policy in Middle East is based on its 2016 “Arab Policy Paper” (4). Two proclaimed focus areas were- energy security and trade & investment. But alignment between theory and practice is not a character of Chinese foreign policy. China uses its economic clout for geopolitical motives and vice versa. India’s relations with two West Asian regional powers- Turkey and Iran, have taken a nosedive in recent years. India’s troubles in Middle East stem from growing Chinese influence in the region. Iran, an age-old ally of India, has shown inclination toward China. India didn’t receive any invitation to develop the rail link connecting Zeranj province of Afghanistan with Chabahar in which India has invested nearly $8bn rather China was chosen. Chinese economic clout has bought Turkey closer to China. Turkey allied with Pakistan, another China’s ally, to condemn India’s action to abrogate J&K. China’s prime interests are its energy needs and hence, it has tried not to involve in any regional issues. So, we see more of “passive China” rather than “active China” but the passiveness is firm enough to secure its vital interests, even at the cost of India.

Side-lining of India in Africa owes as much to China’s footsteps as to India’s indifference. India has long neglected the crucial geopolitical and geo-economic continent of Africa. Till last year, India had only 29 embassies with China already having more than 50. (2) Beijing’s deeper pockets had given it a greater strategic space in Africa. ONGC lost the bidding to Chinese in Angola’s major oil block is a case in point. (3) China, through its debt trap tactics, holds the strings in Africa which aptly explains why it has been able to secure its first military base outside mainland in Djibouti. Not only in western flank of Indian Ocean, India has moved down the ladder in eastern flank also.

ASEAN – the mouthpiece of South East Asia has not been immune from “growing wings of Dragon”. ASEAN instituted as a potential “US shield in East Asia against Communism” has been turned onto its heads. China follows the anachronistic “carrots and sticks approach” in ASEAN. Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and even Vietnam are cozying up to China while Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore fears the Big Borther (5) Philippines and Indonesia have island disputes with China and its boats are regularly rammed by PLA Navy. Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore are still under US’s shadow. Tatmadaw’s Myanmar is also strengthening its ties with China. Although, India’s economic relations are growing with ASEAN but a divided ASEAN on security front could limit India’s efforts at containing China’s growing military footprint in ASEAN

So, India’s decline vis-a-vis China in its periphery is evident. But India has not been sitting on its hands rather India has taken a pro-active stance in recent years. This was exacerbated after 2020 Galwan crisis when the illusion of “Hindi Chini Bhai Bhai 2.0” and the idealism of Asian century was shattered.

Elephant Trumpets

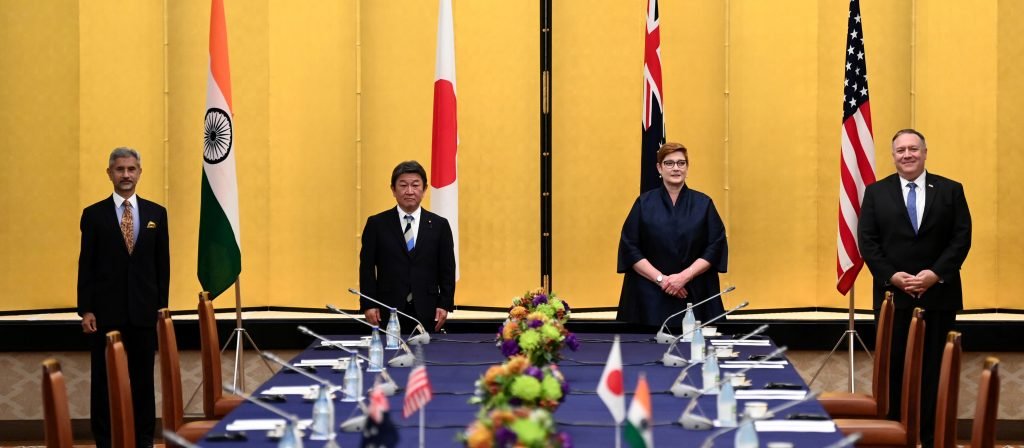

The consensus of functionalism i.e cooperating on issues of low politics(economic) while ignoring high politics(border) issues established after 1992 and 1996 agreements tore apart when EAM S Jaishankar said India “can’t have great relations with high friction border(5.) Galwan has bought an astounding change in foreign policy approach of India. India went on to “internationalise” the aggression, openly deviating from past precedents of keeping it within closed doors of diplomacy. Heated Himalayas has resulted in warmth elsewhere. India’s long affair with Quad has now culminated into a full-fledged marriage and constant Chinese brinksmanship is deepening this bond. Quad leaders met for the first time, for an in-person Summit in US. EAM S Jaishankar defined Quad as “not against something, but for something”. Tanvi Madan explained it as a “quest for a rule-based international order”. She mentions it is invariably anti-China- as being an authoritarian organisation, CCP and laws/rules are at loggerheads with each other. Along with global balancing, India has also worked for regional balancing.

Political and economic churnings in South Asia have helped India regain its lost sheen. Nepal saw return of Nepali Congress from a Communist coalition. Nepali Congress Party historically shared strong ties with India since 1950s. Maldives have Mohammad Saleh in power whose government openly adopt “India First Policy”. Sri Lankan economic crisis has bought the train back on path which was derailed after Colombo unilaterally reneged on India- Japan- Sri Lanka Tripartite agreement (6.) Even relations with Pakistan have seen signs of thaw. Pakistan PM praised India recently and even Army General Bajwa proposed talks for resolution of disputes. So, India is standing back to its feet after suffering losses. This comes after a sharp realisation that India needs more proactiveness rather than fence-sitting.

Indo- Pacific has emerged as a flashpoint of major geopolitical, geostrategic, geo economical churning. As PM Modi said during Shangri la Dialogue- Indo Pacific is going to define world politics for 21st century. Beijing’s growing overtures in Indo- Pacific have made India nervous which considers it as “its backyard, its swimming pool(7) The major source of influence is through its Belt and Road Initiative. Given India’s economic limitations, it adopted two-pronged approach regarding BRI. First, India highlights the inherent weakness in Chinese projects i.e debt laden, unsustainability, environmentally polluting, etc. In Munich Security Conference 2022, Jaishankar stated- “debt becomes equity, equity becomes something else”. Secondly, India has proposed grants and aid wherever possible and also collaborated with developed countries like Japan, EU, and US for providing alternatives. Several multilateral groupings have emerged to coordinate actions among Indo-Pacific countries including India such as IORA, IONS, BIMSTEC etc. Recently concluded Colombo Security Conclave has added a new page to India’s Indo-Pacific playbook

Dragon- Elephant Collision?

Dragon’s exponential leap and dwindling balance of power will ultimately fuel China’s aggression not only in India but elsewhere also. India’s foremost objective is to prevent or deter any Chinese aggression on borders. Given the huge capacity difference, India needs a “rainbow of approaches” rather than just a military approach. It has to include military, economic, political, and even cultural aspects. China’s confrontation with US in South China Sea constraints PLA to deploy significant assets toward Himalayan border. India needs to “match the maximum possible assets” that PLA could bring to Himalayan borders or Indo Pacific. Whatever is left can be taken care of by forging close partnership with Quad and coordinating response during crisis. India needs to convey Chinese side that any misadventure in Himalayas would be unfruitful for CCP. However, India should note that military measures alone are insufficient and unsustainable in long run.

India needs to shift its gear of economic growth for a sustainable military initiative. Since 2017 economy is under slowdown and Covid-19 has added salt to the injury. Without having economic power, it is almost impossible to take on China(8) Coupled with that India should seek to decouple its economy with China in a sustainable manner and work on its capacity building and infrastructure creation. Prevailing environment of deep mistrust and geopolitical competition that exists between the West and China and India’s growing economic prowess provides India a “once in a century” opportunity to gain most out of it and place India in the “league of $10 trillion economies”.

What makes India fares better than China is the positive perception that countries’ have for India. China’s wolf warrior diplomacy and arm-twisting tactics did more damage than benefitting it(9) India should capitalize on this front. India needs to show its inner “Samaritan” to the world exemplified in her vision of Vasudhaiv Kutumbakam. India can win “not only friends but allies” by doing so. Using this, India can create acceptance not only for its economic interests but also security as well as global interests.

A room-sharing deal between dragon and elephant seems a distant dream, so world will witness an increasing dragon’s fire as well as elephant’s trumpets. Whoever wins will shape not only Asian geopolitics but also the emerging new world order. India needs to play its cards meticulously and nimbly in order to “duck” dragon’s offensive and seek “rightful place in comity of nations”