Dealing with the Dragon: Does India Plan to Slay or Stay Away?

Since the onset of the pandemic, Indo-Chinese relations have been hit. It first started with the clash in the Galwan valley that embarrassed Beijing to the point of not letting even family members of the deceased be informed following the clash. After this flashpoint, while the world opened up to the new normal, China remains under strict restrictions due to the barbaric Zero Covid policy. As the average Chinese citizen took to the streets and braved the wrath of the Chinese Communist Party, the Indian Army thwarted another illegal advance by Chinese troops, this time in Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh, India.

These series of trials by fire now beg of New Delhi to answer the fundamental question: will it engage with China on the battlefield?

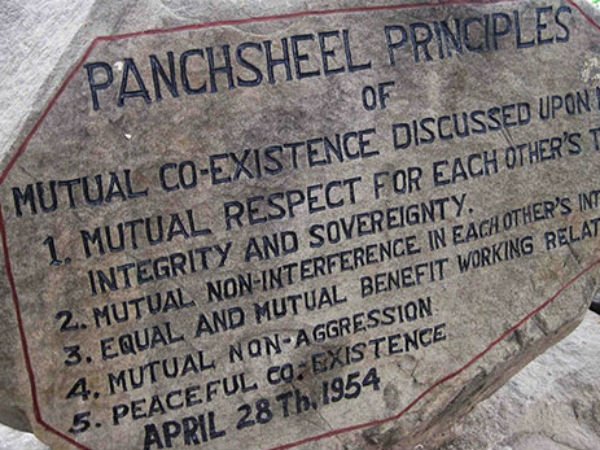

Panchsheel and the Killing of Doves

Jawaharlal Nehru created his initial visit to China in 1954 when he met the Chairman of the Communist Party of China, Mao Zedong, to cement the ties between the two countries and to hold on forward the five principles of peaceful co-existence, that is, Panchsheel. Then the “Hindi Chini Bhai Bhai” saying came into vogue. The Panchsheel was a set of five principles for peaceful coexistence and mutual non-aggression that Nehru and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai during the 1950s proposed. The five principles of Panchsheel are

- Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty.

- Mutual non-aggression.

- Mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs.

- Equality and mutual benefit.

- Peaceful coexistence.

The Panchsheel principles were incorporated into the 1954 Agreement on Trade and Intercourse between the Tibet Region of China and India, and they were also included in the Bandung Declaration of 1955, which was signed by 29 Asian and African countries and recognised the importance of peaceful coexistence and non-interference in the affairs of other countries. The Panchsheel principles have been an important part of India’s foreign policy and have shaped its relations with China and other countries.

However, China’s plans were altogether totally different. Nehru’s naïve trust in the Chinese embodied within the saying, “Hindi Chini Bhai Bhai,” was repaid with China’s invasion of India on October 20, 1962. China launched an offensive across the border, quickly routing the Indian forces. As India’s line of defence was broken, Nehru frantically pleaded for US help, but very little was forthcoming. The war on the roof of the world suddenly was over a month later, even as China appeared poised for a decisive strike. When teaching Nehru a lesson, the Chinese withdrew behind the factual border.

History Repeats Itself

In May 2020, many melees broke out between India and China, one of which was at the glacial lake Pangong Tso. As per reports, Indian troops were severely injured, there were around 20 casualties reported, and Indian soldiers were evacuated through helicopters. Indian analysts said Chinese troops were wounded as well.

The 2020 incident within the valley was a warning call to India’s military and civilian institutions regarding the danger of future, broader confrontation with China and its well-equipped defence force — and therefore, they must be compelled to counter it. India conjointly prohibited dozens of Chinese mobile apps, a part of a drive to bolster its defences in a group action Narendra Modi’s government believes is being fought on the technological front too.

After the valley clashes, India redeployed six army divisions from its northern front along the border with its traditional foe Pakistan to the north of Ladakh. Last year, Bipin Rawat, then India’s Chief of Staff, represented China as India’s biggest security threat. The Chinese were building villages, presumably for billeting and locating their civilians or for the military in the future right along the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

On December 9, hundreds of Chinese soldiers transgressed into India’s side of the boundary, causing melees between the two. It happened near the Tawang sector of Arunachal Pradesh state, the eastern tip of India. Some soldiers suffered minor injuries. Prior to this attack, Chinese drones had reportedly stirred quite sharply towards Indian positions on the LAC in Arunachal Pradesh, which forced the IAF to scramble its fighter aircraft deployed within the region. The army supply aforesaid that there had been accumulated activity in Ladakh by the Chinese military, still as a “possible” airspace violation by the Chinese air force within the same space.

This follows joint military exercises that irked Beijing last month between India and, therefore, the USA within the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand, which borders China. The Chinese troopers conjointly displayed a banner objecting to the Indo-US military exercises.

Triggering Tiger: India’s Counter

The clashes are still reverberating in New Delhi, and analysts say the future conflict between the world’s two most populous countries cannot be ruled out. Arunachal Pradesh has always been the centre of tension between the two nations, causing war outbreaks or melees between indo-china military troops. So, what is India doing to counter China?

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, additionally called the Quad, among Australia, India, Japan, and the United States appears to have flustered China a small amount. In Mauritius, too, India has accelerated infrastructure and development projects to counter China’s scramble for influence in the strategically crucial Indian Ocean Region (IOR).

There was a broader realisation that China’s military power couldn’t be managed by diplomatic agreements alone and would need India to require its military and economic steps. India’s defence spending had already increased by 50 per cent over a decade. New Delhi’s priorities have been to modernise the army and ensure it has sustainable military-industrial capacity.

It is not accurate to say that the government of India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi is reluctant to engage militarily with China. India and China are nuclear-armed countries with a history of border disputes and other tensions. Still, they have also been involved in diplomatic and economic relations and have worked to manage and resolve their differences peacefully.

Regarding military capabilities, India and China are major military powers in Asia and have extensive and technologically advanced armed forces. India has a strong military tradition and a well-trained and equipped military, with a large army, navy, and air force. China has the largest military in the world in terms of personnel, and it has made significant investments in modernising its military in recent years. It also has a large and growing navy and a powerful air force.

It is difficult to predict the future, and it is not appropriate to speculate on whether India and China will ever engage in a conventional war. Both countries have an interest in maintaining regional stability and avoiding conflict. It is in the interest of both sides to work towards resolving their differences peacefully through diplomatic means.

Simmering tensions between the two involve the danger of step-ups – which is often devastating given each side is established nuclear power. There would be economic fallout as China is India’s biggest commerce partner. The military stand-off is reflected by growing political tension that has strained ties between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping. Observers say talks are the sole approach because each country has much to lose.