Miracle on the Han River — South Korea’s Economic Development

The Korean War from 1950 to 1953 had devastating effects on the population of both nations due to their hostile division. Families were torn apart with no form of communication and left South Korea in a state of poverty. While this impact in itself was colossal, South Korea had the added burden of not being left with any natural resources to revive their economy. This, therefore, led to South Korea being an underdeveloped economy, completely reliant on its agrarian produce and foreign aid from the US.

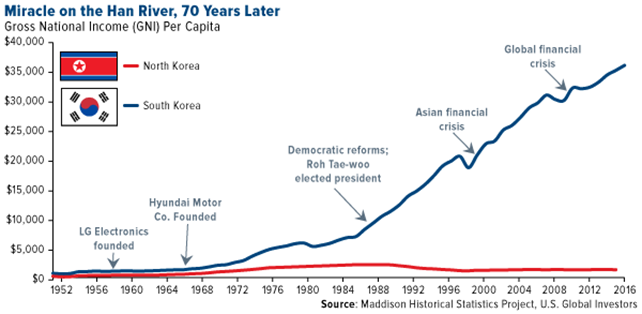

The South Korean economic model, also known as the Miracle of the Han River refers to the rapid economic growth in South Korea after the Korean War. In less than two decades South Korea saw a pragmatic shift in its economy and is currently the 12th largest economy in the world according to its GDP.

This heightening of South Korea’s economy can be factored by 3 principal factors:

- Investments in rebuilding an education system and innovations

- Eliminating an agrarian economy

- Withholding dynastical mega-corporations

Prior to the Second World War and the Korean War, South Korea had the foundation laid for a vocational training system. However, this was disrupted by the aftermath of the wars and completely shattered their system. Resultantly, the government started focussing on rebuilding their educational and vocational training system with the sole purpose of increasing employment which would have the dual benefits of eliminating poverty.

The implementation started with compulsory school attendance from ages 6 to 15 and in the 1970’s South Korea set an equalisation policy which aimed at reducing competition to get into prestigious secondary schools. In “equalisation zones” students were taken into consideration for a prestigious secondary education by a lottery system. Although many parents were opposed to this idea since these students were not admitted on the basis of merit, these policy-induced parents from equalisation zones, which were primarily regions that were less developed, to send their children to school and fulfil the minimum requirements to be eligible for this policy.

A significant chunk of South Korea’s economic restoration post the war is attributed to the willingness of citizens to enrol themselves into the educational system while also having the flexibility to opt for vocational training after secondary education. This was made possible by the government’s investment in human capital which promoted innovation and developed a good workforce for the nation.

This brings the model to its second aim of eliminating an agriculture and cultivation based economy. South Korea started focusing on industrialising its rural areas and bringing them out of the realm of subsistence farming. This happened as a result of increased literacy rates and investments in infant industries by the government which led to more job opportunities. Hence, bringing citizens out of villages.

In addition to investments in building human capital, South Korean ties with the US majorly helped the country in picking up its pace as far as investments in infant industries are concerned. During the Vietnam War, South Korea contributed by providing troops to the US military. In return America harboured trade ties with South Korea which increased the cash flow into the country, hence, increasing the government’s revenue.

After achieving the first two goals of its plan, the South Korean government was now in a position to carry out mass production, at a globalised level. However, Japan was already a regional supplier of electronics, automobiles and technological gadgets, all of which Korea had expertise in. This initially made it challenging for South Korea to gain an edge over the Japanese suppliers. Gradually, due to Japan’s spurge of development, the costs increased which therefore helped South Korea gain a comparative advantage in the aspect of supplying cheaper produce on a global scale.

With this plan resulting in the continued growth of the South Korean economy, the government now moved to its third aim of the economic model. This aim consisted of sustaining the progress and the firms involved in the growth of the country. The government started backing “Chaebols” which refers to family-run businesses that are passed on and run within the family. In the late ‘70s, the government realised the rate at which these companies were growing and assured support by ensuring a cash flow from the government’s side and urged the firms to focus on growing. Today these family dynasties have become mega-monopolistic corporations, run namely by Samsung, LG and Hyundai. These three companies alone are responsible for 2/3rd’s of the entire Korean economy and produce for the three main industries of the country- ship manufacturing, automobiles and electronics.

Whilst this strategy to make the economy reliant on just three major corporations has turned out to be extremely lucrative for South Korea but it has now become too big to fail. This essentially means that in case of an economic crash or an obstruction in the mechanism of any of these companies, thousands of people will lose their jobs, stocks will fall and the economy will most likely experience a recession.

With the COVID-19 pandemic gaining momentum globally, the South Korean economy, like many others, faced a recession and saw a fall in their GDP for the first time in 17 years. Nonetheless, the South Korean Finance Minister is optimistic that the nation will be back on track by the third quarter much like China. Since South Korea does not have a geographical terrain as large as China and the natural resources, the government will have to continue their already undertaken policies of fostering education and innovation to revive its economy once again.