Indonesia prefers Japan over China on its second rail mega-project

Indonesia intends to pick Japan as its partner in a multibillion-dollar rail link connecting Jakarta to Surabaya – crushing China’s bid to secure its second major infrastructure project on Java, Indonesia’s most populous island.

Luhut Panjaitan – Indonesia’s coordinating minister for maritime affairs, whom President Joko Widodo has put in charge of the country’s ties with Beijing – acknowledged Beijing had expressed interest in the project, with the chairman of state-owned China Railway Construction Corporation visiting him earlier this month.

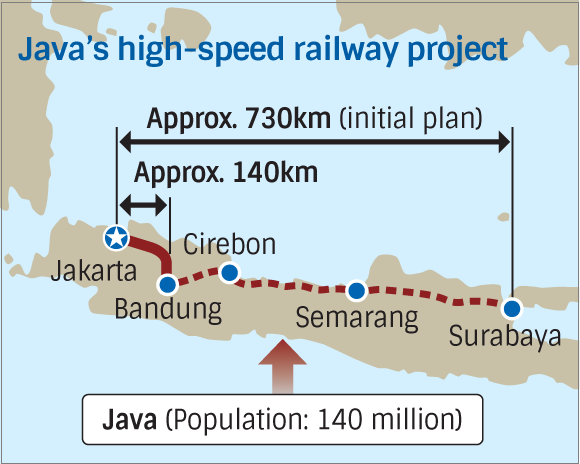

Still, he said Indonesia still preferred Tokyo as its partner in the 720km semi-high-speed rail link between the nation’s current capital and the second-biggest city in east Java. Indonesia is planning to relocate its political and administrative centre from Jakarta to a region on Borneo Island and expects to start moving some of its bureaucrats by 2024.

“It will be a little difficult [for China to get the project] because Japan wants it, and we also see Japan as an [long-time] investor in Indonesia,” the 71-year-old former generals told reporters this week. “I think we are progressing enough [with Japan].”

This isn’t the first time Jakarta has had to choose between Japan and China in major construction projects as Widodo seeks to drive economic growth by plugging infrastructure gaps across the archipelago of some 17,000 islands.

In 2015, KCIC – a consortium of Indonesian state-owned companies and China Railway Construction Corporation – beat the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) for the US$6 billion, 142km high-speed rail link connecting Jakarta to Bandung in West Java.

Back then, an official from Jakarta’s State Enterprises Ministry suggested it was because the Chinese did not require a loan guarantee from the Indonesian government, while Japan offered a cheap loan with low interest but with Jakarta bearing the risk if the project fell through.

Japanese investment had earlier won Indonesia’s heart after Jakarta opened its long-awaited Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) subway system in March, the US$1.1 billion construction of which funded by a soft loan from JICA. Jakarta is now building the second phase of the MRT – also funded by JICA – that will connect the city centre to west Jakarta and cost 25 trillion rupiahs (US$1.8 billion).

Analysts said there was no need to read too much into the government’s decision to go with Japan on the Jakarta-Surabaya rail link, and that Indonesia was not picking sides given the continuing US-China trade dispute.

“Accepting one or 20 deals does not mean anything especially if you look at the overall [amount] of deals that the recipient states get,” said Alvin Camba, a researcher of Chinese investment in Asia-Pacific and doctoral candidate at Johns Hopkins University.

“Japan has been Southeast Asia’s biggest investor since the 1980s, displacing the United States and many former colonial powers. A lot of people assume that China is the big thing, but Japan never went away and it’s always had considerable influence in business and politics.”

In recent years, Beijing has scored big projects and a relatively large share of new deals, but Southeast Asian states remain careful to strike a balance between Beijing and Tokyo, which remain top trading partners for most of them.

For example, the Philippines gave its Northrail project to Japan while the Southrail project was awarded to China, and both countries built different phases of the MindaRail project, the Philippines’ longest railway, Camba said.

Indeed, Japan still tops China in terms of being a major infrastructure investor in the 10 ASEAN nations, though the gap is narrowing. As of June Japan had funded 240 projects in the bloc, compared with China’s 210, according to data from research consultancy Fitch Solutions.

In the region’s six biggest economies – Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam – Japanese-backed ventures are valued at US$367 billion, compared with China’s US$255 billion, the data shows.

However, Beijing has more active infrastructure projects than Japan in Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, and Malaysia, while Japan has the upper hand in the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, East Timor, and by and large in Vietnam. The two countries are tied in Myanmar, with 16 infrastructure ventures apiece, Fitch data shows.

In Indonesia, China’s investment is rapidly catching up to Japan: Beijing invested US$2.4 billion last year, while it had already invested US$2.3 billion as of the second quarter of this year, according to data from the Indonesian government.

Indonesia is also in no position to favour one investor over another, analysts say, as it is failing to reap the silver lining from the US-China trade war. Foreign investors seeking to relocate from China are reportedly flocking to Vietnam, Malaysia, Cambodia and Thailand over Indonesia. Net foreign direct investment (FDI) inflow only accounted for 1.9 per cent of its gross domestic product last year, compared with Cambodia’s 11.8 per cent and Vietnam’s 5.9 per cent, according to World Bank data.

“Indonesia needs to be more clever in taking advantage, as much as it can, of the US-China trade war. It is slower to attract foreign investors than other Southeast Asian countries,” said Edbert Gani, a political economist with Indonesia’s Centre for Strategic and International Studies. “Widodo has indicated that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs will also be tasked with attracting more FDI in his second term, but I don’t see this as Indonesia [taking sides] in the US-China proxy war.”

Indonesia expects to spend up to 60 trillion rupiahs (US$4.2 billion) on the Jakarta-Surabaya project, under the Japanese estimate of 90 trillion rupiahs. Jakarta is planning to start construction by 2020 and complete the project by 2023.

“The benchmark is to cut the 11-hour [journey] into 5.5 hours. There are few details but we know it’s no shinkansen, no express train,” Japan’s ambassador to Indonesia Masafumi Ishii said during a discussion with foreign journalists in February. “We are trying to make the best use of existing infrastructure and improve it with a limited amount of money. Electrifying [the railway] costs too much.”

Speaking to reporters on Monday, coordinating minister for maritime affairs Luhut added a caveat to the Japan tie-up. While the two countries have yet to sign a memorandum of understanding, Japanese state development body JICA is currently holding a two-year feasibility study for the project. Once the deal is official, Jakarta hopes Japan will use domestic raw materials while transferring its technological know-how to Indonesia.

“Japan cannot do whatever they want [in the Jakarta-Surabaya railway project]. They should not [prevent the technology transfer to Indonesia], like with the MRT project,” Luhut said, referring to the US$1.1 billion JICA-funded subway network in Jakarta. “We also have local content and technology transfer [requirement].”

The Jakarta-Bandung rail link is China’s only Indonesian project under the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ambitious global trade strategy that now covers more than 150 countries. Jakarta is, however, keen to channel further belt and road investments into four “economic corridors” to boost growth and infrastructure across the country.

China won the project due to its readiness to provide guarantee-free loans, while Japan requested Indonesian Government funding/ Image: Railway-Technology

Construction on the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway is expected to be completed by 2021. KCIC on Wednesday said it had acquired “99 percent” of the land needed for the link, which will cut the journey time between two cities to 40 minutes. KCIC is also set to receive another loan of US$400 million from China Development Bank to speed up work on the 142.3km project.

The link has been delayed by several issues, including mismanagement and land acquisition. The latter is the top problem hindering FDI inflow to Indonesia, as well as red tape delaying the issuance of operation permits. Regulatory uncertainty and a lack of fiscal incentives are the other reasons foreign investors prefer Vietnam and Malaysia over Indonesia, analysts said.

An earlier version of this report was published in the South China Morning Post