Whither the Iran Nuclear Deal?

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The incoming Biden administration is keen to return to the nuclear deal with Iran, provided it contains “some amendments.” This is in contrast to the Europeans, who are mostly willing to return to the agreement as it stands. The director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is demanding that a new nuclear agreement be signed, or at least that the previous agreement be changed in such a way as to prevent Iran from achieving nuclear break-out.

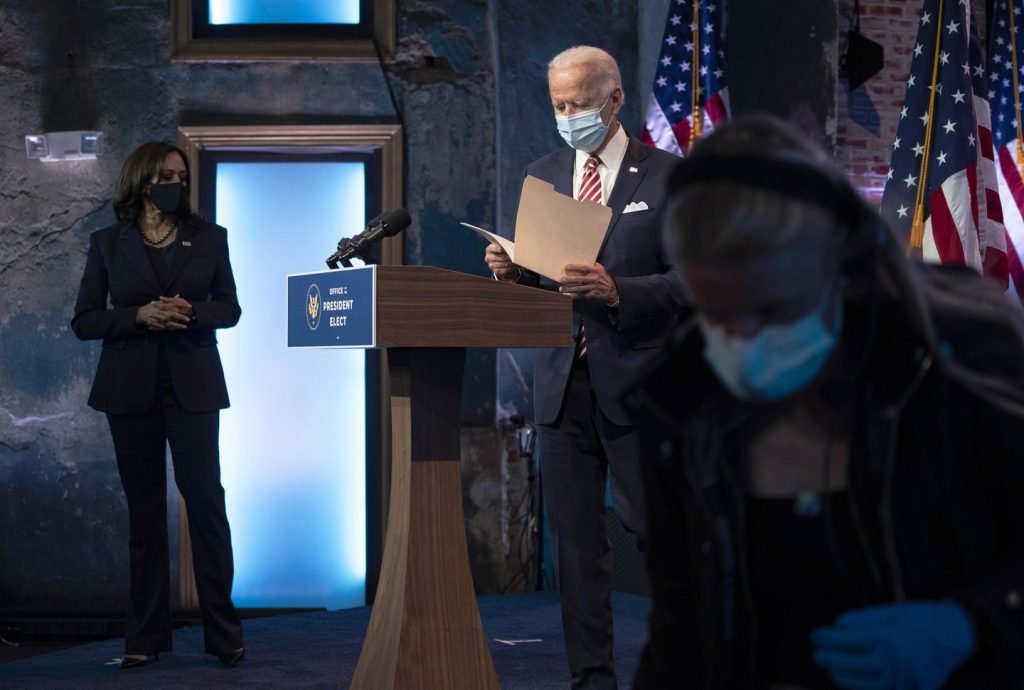

In an interview with Reuters on December 17, IAEA D-G Rafael Grossi expressed disapproved of President-elect Joe Biden’s pledge to return to the JCPOA agreement, the nuclear deal signed in 2015 between the five powers and Germany (P5 + 1) and Tehran. Grossi said:

I cannot imagine that they are going simply to say “We are back to square one” because square one is no longer there… It is clear that there will have to be a protocol or an agreement or an understanding or some ancillary document which will stipulate clearly what we do…There is more [nuclear] material… there is more activity, there are more centrifuges [in Iran].

Biden stated in an interview he gave on July 30, 2019 that he intends to return the US to the nuclear deal, albeit with amendments, and lift the sanctions imposed on Iran by the Trump administration. As for Iran, it has announced its readiness to return to the 2015 nuclear deal provided the agreement is not altered.

In light of recent developments regarding the Iranian nuclear program, such as the killing on November 27 of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, architect of Iran’s military nuclear program, and the findings released by the IAEA in its quarterly report of November 11, it is difficult to see how Biden can turn his intention to return to the nuclear deal into reality. Much depends on the people he appoints to carry out his plan. One likely candidate is Tony Blinken, former Deputy Secretary of State in the Obama administration and Biden’s nominee for Secretary of State. Blinken recently announced that he would try to improve the Iran deal, but believes rejoining the deal is an “urgent” priority.

It remains to be seen whether Biden will appoint members of the original US delegation to the JCPOA agreement, who included then-Secretary of State John Kerry; then-Secretary of Energy Ernie Moniz; Wendy Sherman, who served as Deputy Secretary of State; and Ben Rhodes, Barack Obama’s personal adviser at the time.

In the latest IAEA report, an emphasis was placed on Iran’s January 5 announcement that its nuclear program would no longer be “subject to any restrictions in the operational sphere.” This declaration followed Iran’s 2019 enrichment of uranium beyond 300 kg of UF6 (uranium hexa-fluoride compound), the uranium content of which is 202.8 kg. Iran also increased the enrichment rate to 4.5%, beyond the agreed limit of 3.67%—a violation of the nuclear agreement.

According to the IAEA report, the amount of uranium Iran has enriched since then exceeds 2.4 tons. The report contained detailed references to Iran’s violations of the nuclear agreement on the development and production of advanced centrifuges, as well as the start of their operations on an industrial scale, which could allow Iran to shorten the enrichment period and enrich uranium for nuclear weapons.

The EU and the other signatories to the JCPOA nuclear agreement (with the exception of the US) appear for the most part to be willing to return to the agreement as is, despite the lengthening list of Iranian violations—but they call upon Tehran to refrain from destroying the chances of a diplomatic return to the agreement once Biden takes office as US president. There are indications that France takes the threat of Iranian violations somewhat more seriously than Germany and Britain. The French FM’s response, when asked if a new protocol is needed for the nuclear deal, was that Iran’s actions are becoming a serious problem, especially their activities in the field of enrichment.

Another event that affected the attitude of the EU and its member states toward Iran was the execution of Iranian journalist Ruhollah Zam for his role in anti-regime protests. According to EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell, Zam’s execution was the reason why some EU member states canceled their participation in the Europe-Iran Business Forum in December. He added, however, that the EU’s talks with Iran on the nuclear issue would continue. Europe’s approach is thus much the same as it was before the signing of the agreement in 2015. Then and now, the EU was enthusiastic about reaching a deal—possibly at any cost.

In the background, of course, is the killing of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh. On December 3, the Majlis passed a series of nuclear-related decisions in response to the killing. Particularly notable was the decision to increase uranium enrichment to 20% and accumulate at least 120 kilograms of enriched uranium for this rate, an activity that could bring Iran very close to the ability to produce nuclear weapons. Other significant decisions were uranium enrichment to at least 500 kilograms per month and the resumption of the construction of a heavy water reactor (IR-40) suitable for the production of plutonium for nuclear weapons, a project that had been close to completion before the signing of the nuclear agreement in 2015. It was also reported that if the nuclear deal does not return to its original state, Iran might consider itself released from all its commitments to the IAEA.

On the other hand, the Iranian Foreign Ministry announced that it opposes the bill, and President Hassan Rouhani has said he would refrain from signing the Majlis decisions and ratifying them as laws. He shrugged off his country’s ultra-conservatives, who could miss the “opportunity” presented by the change in administration in the US.

Iran is thus in the middle of a triangle. One leg is the IAEA, another is the non-US signatories to the agreement, and the third is the US.

The IAEA is constantly on guard against Iran’s nuclear mischief. Grossi appears frustrated that the question of whether or not to continue the nuclear deal has arisen on his watch, and he may feel the Iranians are deliberately trying to provoke him and the Agency. It is likely that he wants to get out of the matter with a viable agreement in hand.

The EU’s member states, as well as Russia and China, are less troubled by fear of an Iran in possession of nuclear weapons. In their view, Iran has great potential as an economic partner. As for the US, its position on the issue is not yet clear.

Iran itself is divided between ultra-conservatives and pragmatists. The ultra-conservatives oppose any compromise and strive to reach nuclear weapons at some point—preferably soon. The pragmatists, aware of their country’s economic situation, are trying not stretch a fraying rope beyond the point of no return.

This article as originally published by BESA Center