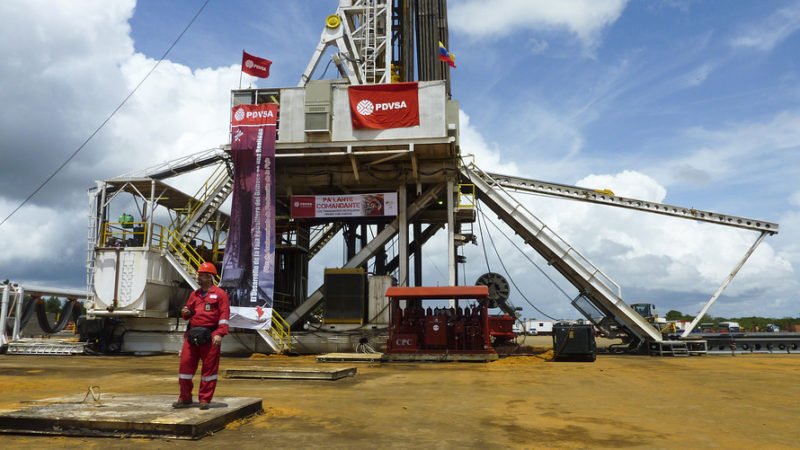

Venezuela’s oil industry amidst a year of sanctions

Venezuela’s oil exports have steadily risen in recent months, throwing a lifeline to President Nicolas Maduro, as Washington has failed to make good on threats to deal a death blow to its oil industry since sanctioning state oil company PDVSA a year ago.

Following the Jan. 28, 2019 ban on U.S. firms importing Venezuelan crude, the United States has not followed through on threats to extend the sanctions to any foreign company doing business with PDVSA, as it seeks to oust socialist Maduro.

The result: companies that had stopped lifting crude at Venezuelan ports in the wake of the sanctions are now sending tankers to the South American country again – including U.S. oil major Chevron Corp, India’s Reliance Industries and Italy’s Eni).

And Russia’s Rosneft, which became the largest intermediary for Venezuelan oil last year at time when few were willing to trade it, shows no signs of backing off.

Breaking with two decades of socialist orthodoxy, PDVSA has also given more leeway to private sector partners in joint ventures to handle crude exports and to run operations, as it seeks to weather the impact of sanctions.

As a result, in December Venezuelan exports bounced back to 1.1 million barrels-per-day (BPD) – well below pre-sanctions levels but steady improvement from August, when exports sank to below 800,000 BPD.

“Patriotic oil workers turned the imperial blockade into a challenge and an opportunity,” PDVSA said in a Jan. 16 statement touting the performance of some of its oil upgraders near the Jose terminal, which convert the sludgy crude from the Orinoco Belt into exportable grades.

Neither PDVSA, the Venezuelan government nor the U.S. Department of State responded to requests for comment.

The modest recovery by no means suggests Venezuela is back to the boom times of the early 2010s when output above 2 million BPD funded generous social spending by the late leftist leader Hugo Chavez.

Total exports last year did not recover from the loss of purchasing by U.S. refiners and averaged 32% below 2018 levels.

That had an outsize impact on PDVSA’s cash flow: U.S. refiners, previously its most accessible customers, paid mostly in cash.

By contrast, its shipments to China and the oil lifted by Rosneft go mostly to repay billions in oil-for-loan deals, leaving no cash in PDVSA’s coffers.

The sanctions were far from the only problem facing PDVSA last year. Nationwide blackouts in March and April paralysed output and left many of the electricity-hungry upgraders operating below capacity for months.

PDVSA is still reeling from issues that plagued it well before the sanctions, including a brain drain as high-skilled workers quit in droves as hyperinflation in the crisis-stricken country erodes their salaries.

“The rank and file has only one desire: get out as fast as they can,” one PDVSA manager, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said on Monday.

Draining inventories, making reforms

PDVSA has stayed afloat both because the United States has not policed sanctions as harshly as initially feared and as Venezuela has found creative ways to get its crude to companies that are wary of dealing with it directly.

A hint of what a PDVSA death spiral could look like came in August when Washington threatened secondary sanctions on companies doing business with PDVSA. The ensuing lack of buyers prompted a buildup in domestic inventories to maximum levels, prompting the company to cut output.

But with Rosneft acting as an intermediary and helping to solve shipping bottlenecks, PDVSA continued sending crude to China – its largest destination this year – through ship-to-ship transfers on the high seas, disguising the origin of the oil, according to Refinitiv Eikon data.

And as the United States did not follow through on its threats, Spain’s Repsol, Reliance, Chevron and Italy’s Eni have resumed loadings since the third quarter.

The companies have said they receive the crude in exchange for refined products or to pay down commercial debts – not cash – and are therefore in compliance with sanctions.

Washington has repeatedly renewed a license allowing Chevron and a handful of U.S. service firms to maintain operations with PDVSA despite sanctions.

Despite the nascent liberalisation of the heavily state-controlled industry, its fate is tied to how strictly the United States decides to enforce sanctions.

Washington has pledged to take a “closer look” at Russia’s role but has not yet sanctioned Rosneft over Venezuela activities.

“The sanctions will continue to be the most important issue for Venezuela’s oil industry in 2020,” said Francisco Monaldi of Rice University’s Baker Institute. “What remains to be seen is how much enforcement the United States will decide to do.”