What do Japan’s G7 and India’s G20 presidency mean for the Indo-Pacific region?

The Indo-Pacific region has more growing powers, overlapping economic and political ties, geopolitical flashpoints, and conflict risks than any other region. In the coming years, it will be essential to maintaining international peace and prosperity. Boundary disputes in the South China Sea endanger peace and security despite attempts by nations like Japan and India to serve as a growth engine for the rest of the region and the globe. As China has developed its Belt and Road Initiative, the Strait of Malacca and the Indian Ocean have gained geopolitical importance as maritime routes for natural resources (BRI). From a security standpoint, these geopolitical and geoeconomic concerns have become more complicated as a result of the escalating rivalry between China and the United States during the COVID-19 epidemic.

India-Japan Presidency

On December 1, 2022, India took over as president of the G20, a pivotal moment in the Indo-Pacific region. The G20 is a forum for the world’s 20 largest economies to discuss global issues and find solutions. Every inhabited continent is represented in the G20, 80% of the global GDP, 75% of international commerce, and 60% of the world’s population. However, the G7 democracies—Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, Canada, and the United States—form the group. Germany replaced the United Kingdom as Presidency at the start of 2022, and Japan took over in 2023. For both, India and Japan, the region holds strategic importance.

As the U.S.-China strategic confrontation heats up, there is a growing expectation in the Indo-Pacific area that other middle-power states like Indonesia, Australia, and India must play a proactive role to assure stability. This illustrates the fact that no one state or even a combination of powers can exercise complete control over the Indo-Pacific region because of its sheer size and political and cultural diversity. Since Japan and India have deep ties to the nations of Southeast Asia on many levels (economic, security, and culture), the region looks them to take the lead among the regional middle powers.

India and Japan, being located on opposite sides of the world and separated by an ocean, have never had any pressing strategic concerns with one another. Their mutual pursuit of a regulations system in the Indo-Pacific has made them natural allies in the current struggle against China’s expanding hegemonic influence. In 2014, India and Japan upgraded their relationship to a “Special Strategic and Global Partnership,” The following year, to bring stability to the Indo-Pacific, they established a regional framework that matched up the Free and Open Indo-Pacific with India’s Act East Policy.

Due to their respective locations in the Indian and Pacific oceans and recent took over of presidency, India and Japan are in a prime position to promote maritime stability and partnership. Though the partnership has helped India and Japan become more visible in the Indo-Pacific, threats to their geopolitical interests persist. Even if piracy and terrorism decrease, great power competition has remained widespread. China continues to seek maritime control in the area despite the constraints of an Indo-Japanese partnership. Because of its colossal capital and linkages to the extent established by the Belt and Road Initiative, China has the upper hand in the fight for influence over the region’s littoral governments (BRI).

Given these obstacles, India and Japan must take the benefit of their presidencies to ensure regional development. They must build a more robust convergence of goals about coping with additional influence and defending geopolitical interests in the area, such as focusing their efforts on more practical projects such as the IPOI. By using the platforms of G7 and G20, India and Japan may realise the goal of a free and open Indo-Pacific by demonstrating their relations with other regional governments and setting a precedent that others can emulate.

India and Japan are UNCLOS parties, having respectively ratified the agreement in 1995 and 1996. This legal framework provides predictability and stability to the India-Japan collaboration in the Indo-Pacific. The India-Japan Statement Of vision of October 2018 confirms assuredly the engagement to pursue “peaceful resolution of disputes with full respect for legal and diplomatic processes following universally acknowledged international law principles even those evidenced in the UNCLOS, without the use or threat of force.” In order to protect their respective national interests in the Indo-Pacific region, India and Japan rely on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and related United Nations Security Council resolutions on maritime security. Since they have made it clear that they want permanent seats on a reformed United Nations Security Council, these two platforms will undoubtedly meet their desires.

Visible outlines of India and Japan working together in the Indo-Pacific have already shown good influence, bringing a strong advocate for international cooperation into the area. Given this fact, it’s not hard to see how the partnership may rapidly grow and completely alter the western Indo-Pacific centred on the Indian Ocean.

Southeast Asia is a vital connection between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, thus Japan and India should assume a more proactive leading role in the Indo-Pacific region generally and in this region specifically. Japan should take the lead among the G7 economies in fostering regional economic cooperation. Since China is also a member of the G20, it is difficult for India to make crucial judgements, especially with regards to China’s containment. Countries in the Indo-Pacific are drawn to China’s Belt and Road Initiative because of the region’s great need for infrastructure development (BRI). Even while the USDFC has no prior experience in the Indo-Pacific region, its recent establishment is nonetheless quite promising. Japan and India have extensive expertise in private investment and public and private finance, respectively, and therefore it is logical to expect them to take the lead in implementing concrete and coordinated measures in this area.

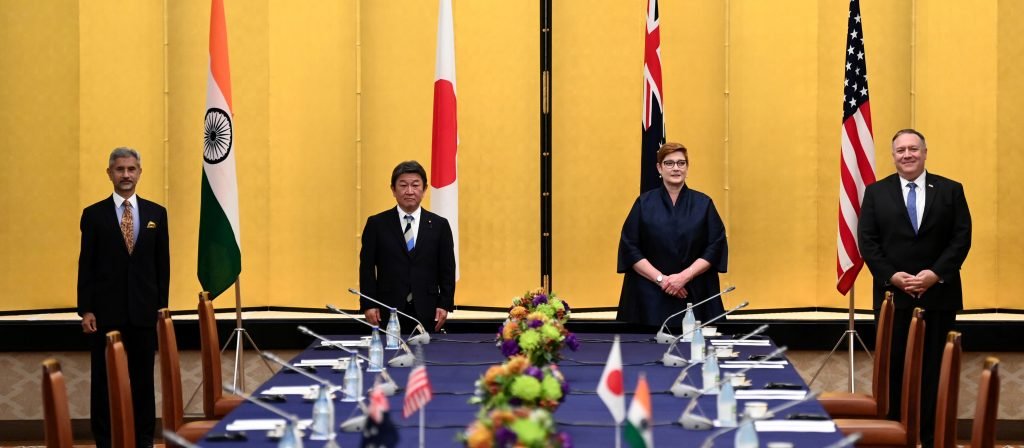

India and Japan’s collaboration in the Indo-Pacific was greatly facilitated by the Quadrilateral Dialogue, popularly known as the Quad. Japan, Australia, India, and the United States all sent armed forces to help with relief efforts after the 2004 Tsunami in the Indian Ocean. To supplement cooperation among naval democracies, the Indian and Japanese presidency might leverage ASEAN nations to participate in the Indo-Pacific, expand their efforts to safeguard the rule of law, strengthen maritime cooperation, and encourage independent solutions to regional concerns.

Conclusion

According to the union minister of environment, forest, and climate change, the collaboration between India’s G20 presidency and Japan’s G7 presidency is a once-in-a-lifetime chance to mould the world’s future toward ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’. India and Japan could work together to help the economies and resources of the Indo-Pacific region. To keep the Indo-Pacific open and peaceful and deal with environmental problems worldwide, the G7 and G20 must act. India and Japan must collaborate to lead international talks on climate change, biodiversity, the circular economy, and plastic pollution as they take over as presidents of the G20 and G7, respectively.