The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative: India’s Response

Background

Driving unimpeded trade and ‘people to people bonds’ through one of the world’s largest transcontinental infrastructural projects, The People’s Republic of China has left little to the West’s imagination to secure a counteractive project at the scale of this transaction. Promising coordination between policy and financial integration through the BRI initiative, China seeks to jarringly align the Asian diaspora in a new era of trade, commerce, and economic growth. Reminiscent of the prominent Silk Route, this infrastructural dream project stretches from East Asia to Europe, significantly expanding China’s political and economic influence.

Adjoined with the initiative to advance relations between countries of East Asia and Europe, this outline aims at the development and furtherance of integrity between these nations and continues to devise a vision of the strongest Asiatic influence the West could ever dream of. China’s vision for the Belt and Road Initiative was started in 2013 by President Xi Jinping, who dreamt of expanding China’s economic and political ascendancy beyond what is categorically understood and stereotyped by the rest of the world. Affluent with the resources and the means of surveying these resources into productive consumption goods, Xi Jinping’s intention to create the largest network of continuous, incessant development models has been incremental in realizing how a leader’s vision to drastically define boundaries and barriers are changing, and are ridden with a driving need to break out of a general homogenization, into a wide field of endless opportunities.

Bruno Macaes’ Belt and Road: A Chinese World Order suggests that the initiative aims at China’s attempts to avoid the “middle-income trap” that, many economists believe, develops when rapidly industrializing, export-led, economies move from the early, low-income phase of their industrialization to its middle-income phase. The BRI, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor[i] (CPEC), and its ports in and around the Indian Ocean are not therefore offensive but defensive projects, designed to safeguard the international trade that is the source of its growing wealth.[1] When we look at the fundamental vision behind the BRI, we see that China seeks to remove the unequal barrier of economic wealth acquisition to a proportionate, more tangible procurement of wealth without the additional motive of capitalistic ventures. This is what the middle-income trap does: it lures a country into believing that the income that flows into international trade will positively discharge additional wage hours, and less benefit, which is the ultimate cause of debt and poverty cycles. “China has been an intelligent partner of resource building in this case in terms of the wealth she is assuring to the countries she wants to sign the BRI with. The promise of wealth, and an additional erasure of political instability clinches the ideological supremacy of the Chinese. In his analysis, Macaes implies China became fully aware of the middle-income trap only when wage rates rose by 12% a year from 2009 to 2013. This is what triggered the attempt to move up the production chain, which is at the base of the BRI.”[ii]

The 24 projects in the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, and the three giant railway networks she is building across Central Asia are only a part of the Chinese global motives. There are another 60 port and rail and road projects spread across Latin America, Europe, and the Mediterranean, of which five are in the USA, which are official records of the growing influence of China’s maritime advancements into the world’s most promulgated port systems. This serves as the perfect base for the procurement of the BRI’s interests amongst other countries and releases a detailed pattern of the idea of why naval security systems are primary sources of advancement and growth.

While it is easy to think of these naval programs as direct consequences of the BRI and its vision, it is also important to realize that Xi Jinping’s legacy of building maritime relations comes from the long-standing traditions of the Chinese to lead in power, in the undercurrent of state control and capture, and securing dimensions of resource under the broad structure of nation-building and collective security.

New Silk Road: What Was It Before And How Will It Unfold?

The BRI initiative is adopted based on China’s Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) trade route which connected modern-day Central Asian and South Asian countries with East and West.

The new Belt and Road is announced by President Xi during official visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia in 2013. The plan was two-pronged: the overland Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road. The two were collectively referred to first as the One Belt, One Road initiative but eventually became the Belt and Road Initiative. Xi subsequently announced plans for the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road at the 2013 summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Indonesia.

To date, more than sixty countries—accounting for two-thirds of the world’s population—have signed on to projects or indicated an interest in doing so. In total, China has already spent an estimated $200 billion (about $620 per person in the US) on such efforts. Morgan Stanley has predicted China’s overall expenses over the life of the BRI could reach $1.2–1.3 trillion by 2027.

For the 70 BRI “corridor economies” (excluding China), projects in all sectors that are already executed, in implementation, or planned are estimated to amount to US$575 billion. If completed, BRI transport projects could reduce travel times along economic corridors by 12%, increase trade between 2.7% and 9.7%, increase income by up to 3.4% and lift 7.6 million people (about twice the population of Oklahoma) from extreme poverty.[iii]

The BRI could increase the economic holdings of every country participating in this initiative by tenfold or more. What this tells us is the almost hegemonic sweeping China does when it comes to unfolding her policies and regimes to the world. We realize that she makes use of the entire systemic suppression Asia, as a continent, has had to face, and takes it to her advantage to bring in, well, more systemic power and control. The contingency of the Chinese over resource control, acquisition, and expansion is far more ideologically supreme to other world powers. As we dwell deeper into figuring out how the BRI initiative is tentatively creating an upsurge in political instabilities in developing economies around the world, we realize that the Xi is creating an image of China others could only wish to see of their own.

BRI and Its Implications for China

A Protean Platform: BRI’s belts, corridors, and roads provide Beijing with the versatility to support its foreign and economic policies and create a brand that links multiple streams under one rubric. These include the Silk Road Economic Belt; the Maritime Silk Road; the Digital Silk Road; the BRI Space Information Corridor; and the Health Silk Road.

Win-Win Cooperation: Beijing consistently frames the BRI purely as a win-win economic and development endeavor as part of an effort to promote China’s image as a responsible, benevolent and all accepting power.

Extraterrestrial BRI: Through the Digital Silk Road and the BRI Space Information Corridor, Beijing is providing access to its Beidou Satellite network, constructing digital networks, providing surveillance, communications, “Smart Cities,” and other technologies. These Chinese technologies boost Beijing’s intelligence and surveillance capabilities, while also feeding the collection of “big data” that is useful to military planners.

Disadvantaging Competitors: The BRI network allows China to bring goods to market faster and cheaper than competitors. Dual-use “Strategic Strongpoints” can impede U.S. power projection by complicating things like port access and overflight in the region. China’s provision of digital services creates dependencies and its collection of “big data” creates advantages. China’s trade ties, financial leverage, and expanding engagement are having an impact on the security environment by increasing the operational constraints on the U.S. military, particularly in a crisis when third-party countries may be averse to taking actions that China would oppose.

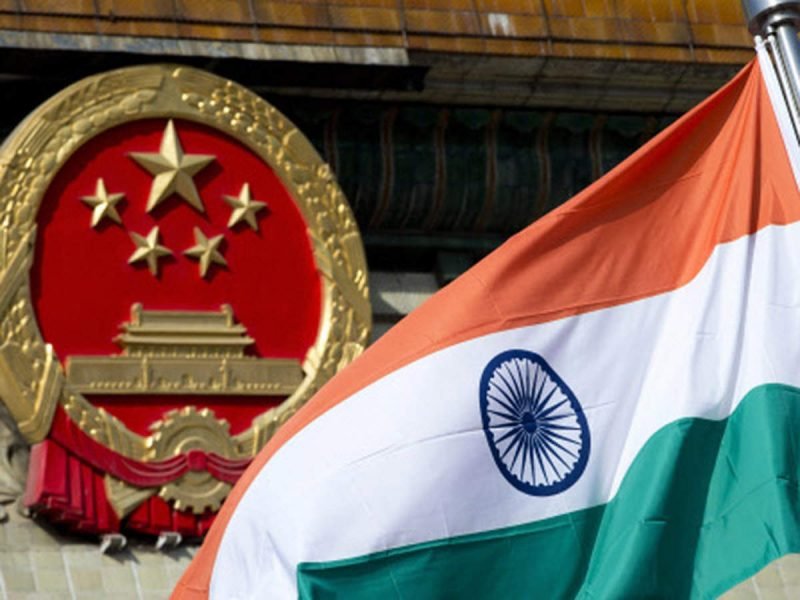

India’s Response

The general Indian view about the nature of the BRI right from the beginning – represented in both the academic and strategic community as well as the government – was that the BRI was less about economic development and more about larger political and strategic goals. Further, while maps from Chinese sources – though never officially sanctioned – always showed India as lying along both a branch of the BRI and the Maritime Silk Route, there was seldom any acknowledgement of the weight of India in economic and political terms in any Chinese discussions of the BRI in general or of BRI in South Asia in particular.

BRI is the closest thing to a ‘grand strategy’ that the Chinese have produced since the waning years of the Qing dynasty in the 19th century. The Indian foreign ministry statement highlighted issues of transparency, environmental protection, economic feasibility, and technology transfer associated with the BRI.

India sees the challenges to the BRI initiative as one of proximity to the vulnerability of this scheme less in development, but more in economic holdings. We see that India has had its doubts about the BRI since its inception, but also conveys that the economic standpoint of China is irreversibly going to benefit the countries involved in the scheme, regardless of their political motives. But, as the global system watches, it is hard to encourage the BRI when we are aware of the drawbacks it has in terms of moral and ethical development and how India is one of the only countries that can see this through.

Conclusion

From the above analysis, we looked at the expansive and almost magic-like vision of the Chinese Republic in forming one of the largest alliances the world has ever seen and converting that alliance into the largest chain of commodity building, selling, resourcing, and producing. We saw that Xi’s China seldom cares about the way the BRI would succeed, but the austereness of which should depend on the high-level skill reformation of the Asian countries. The Belt and Road Initiative has its implications set and bowed down to the last fragment of the magnetic power of money and profit under the lay terms of development and economy building. As a community of global politics, we should critically understand the cultural, political, and economic power hand China is playing when it comes to the BRI.

[1] https://thewire.in/world/china-belt-and-road-initiative-trade

[i] CPEC is intended to rapidly upgrade Pakistan’s required infrastructure and strengthen its economy by the construction of modern transportation networks, numerous energy projects, and special economic zones.On 13 November 2016, CPEC became partly operational when Chinese cargo was transported overland to Gwadar Port for onward maritime shipment to Africa and West Asia,

while some major power projects were commissioned by late 2017.

[ii] https://thewire.in/world/china-belt-and-road-initiative-trade ; Bruno Macaes’ answer is more fine-grained: the BRI, according to him, has been born out of China’s need to safeguard, and expand, the structure of trade relations that it has built since the 1990s, and upon which its internal stability and prosperity now rests. This need has become especially acute since China’s growth began to slacken in 2011. Macaes attributes this to its having, in per capita income terms, entered the “middle income trap”.

[iii] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/brief/belt-and-road-initiative