Was Indira India?

Mrs Gandhi’s declaration of emergency in response to the assurgent

opposition against her led her to undertake her dictatorial powers. The

question is whether she was too experienced not to see threats imposed

on herself and the country.

Politics is the second name of uncertainty; many funny and mystifying things happen in politics regularly that might puzzle us, but we can only figure out why when we have enough authentic information. Although, we can only know about the real why when we can get into the minds of people who took the decisions. Due to limited resources, we cannot do that. Still, we can identify the reasons behind the decision by assessing the leaders’ skills, ideologies, and thought processes for running the nation. Indeed ‘politics is the art of the possible’ (Morris-Jones 1975).

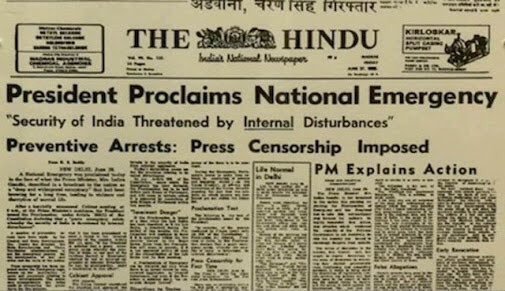

On June 26, 1975, Mrs Gandhi announced the emergency under Article 352(1) of the constitution to fight against corruption, economic slowdown, growing population and political dissent from the opposition parties (Paul 2017). Although the purported goal behind the emergency of June 26, 1975, to March 21, 1977, was to control ‘internal disturbances’ and execute smooth governance and inculcate discipline in the citizens to adhere to the rules made by the government. Mrs Gandhi broadcasted the proclamation all over the country through All India Radio, assuring citizens, saying, “This is nothing to panic about.”[1] Mrs Gandhi emphasized that a grave threat exists against the country’s internal security. These so-called internal disturbances were primarily the strengthened demand for the resignation of Mrs Gandhi by the opposition. This collective urge was because of the corruption charges against Mrs Gandhi filed by her opponent Raj Narain for the Raebareli constituency’s presidential elections[2].

Two Weeks in June: The backdrop of the dramatic events in June takes us back to the buildout of the initial months of 1975 and even the last two years, which overlapped each other or served as the catalyst that led one after one. The forthwith background for the decision of proclamation of emergency was given by the immediate two weeks before June 26, 1975. June 12 was just the beginning of the two most traumatic days for Mrs Gandhi. Justice Sinha passed his ruling finding Mrs Gandhi guilty of two electoral corruption charges, first using local and state machinery in her election campaign and using his private secretary to support her in campaigns before he resigned from his government post. The court found her violating the clauses of The Representation of People’s Act 1951[3], and her presidential election from Raebareli was held invalid. This judgement meant that if the High court of Allahabad did not reverse the ruling, Mrs Gandhi would lose her seat in the Parliament and be forced to resign from the post of Prime Minister and would not be allowed to contest elections for the next six years and will be barred from any political activity till then (Palmer 1976).

The traumatic experience did not end here; the following day, June 13, proved to be a new day with a new shock. The results of state assembly elections in Gujrat held on June 8, and 11 was announced, where congress’s strength fell from 140 to 75. A remarkable attempt of united opposition made the Janata morcha[4] form the ministry headed by Babubhai Patel as the chief minister. And then finally, the high court’s judgement catalyzed reviving the protests against her.

The J.P. Movement: The unusual movement of the opposition famously known as The J.P. Movement against Mrs Gandhi and the congress was led by the charismatic socialist leader Jayaprakash Narayan[5] (commonly known as J.P.). J.P. was considered the Gandhian apostle of non-violence and enjoyed the highest reputation of any prominent Indian for absolute integrity and selflessness (Palmer 1976). However, J.P. did distance himself from politics after his wife’s demise and went back to his home town. After several years of self-imposed non-involvement in politics, he again entered into politics in early 1974, leading the student-protest movement in Bihar.

J.P. Movement served as an Umbrella for the most scattered opposition elements ranging from Hindu conservatives (RSS, Jana Sangh, Anand Marg) to left-wing groups (CPI-M and some groups of Naxalites) (Palmer 1976). Although JP was a known advocate of partyless democracy, he put aside his fundamental beliefs and challenged Mrs Gandhi’s charisma and her corrupt government in Bihar. Ironically, Jayaprakarsh was a close friend and associate to Mrs Gandhi’s father, Pt. Nehru had known Indira since childhood. The J.P. who used to call Mrs Gandhi’ Indu’ was today standing against her party’s popularity. J.P. demanded the elimination of corruption, and for that, he believed that there should be a “total revolution” in India’s social and political life[6]. This movement gained so much popularity that it was seen as the only option for any opposition to survive against Mrs Gandhi. He became the new god for Indians (Palmer 1976). Mrs Gandhi and other congress members tried blackening the character of J.P. and the movement, but it did not die out. Instead, it became a political phenomenon by late 1974 and early 1975. Mrs Gandhi was facing challenges on both the front, constitutionally and extra-constitutional, which she found challenging to deal with; She decided to meet J.P. and reconcile all the differences, but the meeting increased the bitterness and ended the opposite of what was anticipated. From then, Mrs Gandhi’s take on the J.P. movement and J.P. personally became visibly evident, and J.P. became more outspokenly critical of the government, especially of Mrs Gandhi.

The increasing pressure from the opposition day by day was getting difficult to deal with; Mrs Gandhi could not control the agitation, everyday demonstrations, and student rallies against the government. Her firm decision not to dissolve Gafoor’s government in Bihar resulted in increased violent protests by students headed by their beloved J.P. Capitalists joined this movement as they felt Mrs Gandhi could be a threat to the economic and social status of the country. Mrs Gandhi sensed the conspiracy of de-throning her by her opponents. She was somehow managing the protests, but on June 12, 1975, the Allahabad court’s ruling changed the world for her. Her position was in grave threat now; at the beginning of this paper, I mentioned the primary goal behind the decision of emergency as there existed a grave threat to the internal security of India, but was it actually a threat to the country or Mrs Gandhi’s political career.

The Emergency: The Gujrat election results and the Allahabad High court judgment strengthened the opposition movement and demanded Mrs Gandhi’s resignation. Not just the members of the opposition, even congress members expressed the same view. Several Indian newspapers also suggested she should resign until the results of her appeal in the Supreme court of Justice Sinha’s judgment. Surprisingly Mrs Gandhi also considered her exit from the cabinet a wise decision but was not supported by the cabinet as the Congress government lacked the leadership. Congress was heavily dependent on Mrs Gandhi and her continued leadership as no successor could continue the office. Senior Congress leaders like Jagjivan Ram supported Mrs Gandhi’s continuance of office.

Also, the result of the appeal of Mrs Gandhi arrived, the ruling was given by the ‘vacation judge’ Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer on June 24. Two days before the emergency, Mrs Gandhi was given a conditional stay on her prime minister’s office. The judgement turned down the appeal of complete and absolute stay on H.C.’s verdict until the supreme court could examine. Until then, Mrs Gandhi was allowed to continue her office and speak in either house of the Parliament but could not participate in any parliamentary proceedings or draw pay as a member of the Lok Sabha[7].

Mrs Gandhi’s resignation decision was not supported within the congress; her younger son Sanjay Gandhi played a prominent role in influencing Mrs Gandhi not to resign. Her continuance of office was now supported by the legal justification of the Supreme Court. She was again on a course of action to improve her political standing. However, the opposition was not happy with the conditional stay by the Supreme court. On June 25, a significant rally was organized by the opposition groups led by J.P., furiously calling out Mrs Gandhi and her government illegitimate. The opposition’s frantic attempts to question the legitimacy of the Indira government were now getting on Indira’s nerves but were not able to control the demonstrations. However, J.P.’s address to the nation in New Delhi’s rally on June 24, 1975, gave her that opportunity, where J.P. appealed to the military, the police and the civil service to put loyalty to the constitution above the loyalty to the loyalty to the “corrupt” government. J.P. gave a fiery speech reciting Ramdhari Singh Dinkar’s poem ‘Singhasan Khali Karo, Janta hai ati[8].’ Mrs Gandhi interpreted this as the incitation of armed forces to mutiny and our police to rebel.

On the same night, Mrs Gandhi started with a series of brisk events that had catastrophic aftermath for Mrs Indira and the county. In the early morning hours of June 26, she asked the President to proclaim the national emergency and consulted the cabinet and approved the proclamation. The signature’s ink could hardly have dried before the politicians were arrested while the nation was sleeping. A list was already prepared: 676 people were detained in the first few hours of the emergency; later on, the next day, the government spokesperson stated the total as 900, mentioning one-third of them are political detainees and the rest of them as thugs. Besides curtailing the political dissent, other economic criminals like hoarders, smugglers, and tax evaders were also put behind bars (Paul 2017). However, the communication with the official spokesperson started reducing; in contrast, the number of detainees was increased.JP Moraeji Desai Asoka Mehta Raj Narain Piloo Mody, and Jyotirmoy Basu were those famous political leaders who were arrested. The notorious MISA[9] was amended by making the statement of grounds for detention unnecessary; fundamental rights provisions mentioned in the constitution, which were relevant to the detention, were suspended[10]. By early July, some 5000 people were arrested.

Political Imprisonment and Torture: Since 1970, the most commonly used measure for preventive detention was MISA. The act was used indiscriminately during the emergency; detained thousands of people without trial. In Amnesty International report, it was published, evoking the inhumane treatment and the environment of the jails where these prisoners were held. According to the report, it was claimed that these alleged prisoners[11] belonged to the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) and the Communist Party of India (Marxist). They were detained under preventive detention laws, and some of them were also charged with criminal offences. Police brutality has been a critical highlight during the emergency, as Amnesty’s report claims that the allegations of torture of political prisoners increased across the nation during the emergency. In the interview held by Amnesty’s delegation to India, they interviewed seven victims of torture; out of them, two are disabled because of the treatment they received during the detention. The hell included beating prisoners using lathis and guns, quenching cigarettes on private parts, and prolonged hanging upside down, suspended from the knees.[12] These prisoners were not even given resources to fulfil the legal formalities; neither were they given legal assistance nor presented in front of the magistrate within 24 hours. There had been deaths also reported because of the harsh treatment.

Censorship: With the political dissent being silenced, strict censorship on the press was imposed following the emergency decision. Albeit, it was new to the newly independent India to experience such press censorship. Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi were firm supporters of the free press and consistently advocated for fearless expression.[13] Freedom of expression is included under article 19(1), and after the first amendment, press freedom was considered a fundamental right. With the announcement of an emergency, Mrs Gandhi also made sure to cut the power of all the major presses. Mrs Gandhi strongly considered media houses by airing the opposing viewpoints were challenging law and order within the country. Most newspapers could not survive because of the lack of financial support; few could stay but only publish what the government approved. Authorities also issued specific guidelines for the press, which was restricted in a very undemocratic manner. Mrs Gandhi also expelled foreign correspondents and media houses; even the guidelines made it difficult for them to continue reporting from India, as their freedom was the price. Papers and media houses expressed their dissented opinions in the form of blank spaces advertisements, but with the issue of guidelines, everything was halted.

The Judiciary during the Emergency: As L.K. Advani rightly said that the legal profession fared the best and the journalists worst during the emergency (Noorani 1978). The high court had already given a=the judgment against Mrs Prime minister and had once again proven that the judiciary doesn’t work under the pressure of the executive or legislature. However, the supreme court’s decision was undoubtedly disappointing for the bench fraternity, as L.K. Advani rightly said that the legal profession fared the best and the journalists worst during the emergency (Noorani 1978). The high court had already given the judgment against Mrs Prime minister and had once again proven that the judiciary doesn’t work under the pressure of the executive or legislature. However, the supreme court’s decision was undoubtedly disappointing for the bench fraternity. The Judicial crisis caused by the supersession of the three most senior judges in the appointment of the Chief Justice of India demoralized the Supreme court.[14] This instance was a clear indicator that now the judiciary was also working under the combat of Internal dictatorship. However, the bar’s participation during the emergency period was recommendable. The bar made sure of its presence, from vigorously listening to the please filed by detainees or their family members to being openly vocal on the press-censorship issue.

On July 24, 1975, the wife of famous Indian express journalist Kulpid Nayar filed a habeas corpus petition in Delhi High court regarding his detention under MISA. The Delhi high court undertook the petition, and on September 15, 1975, his detention orders were quashed. Justice S. Rangarajan and Justice R.N. A Aggarwal pronounced that personal liberty must be regulated by law in India. The state was asked to produce items against M.R. Nayar but was unable to; as a result, Nayar’s detention was held illegal. Another critical case was the Nathwani case, which challenged the ban on meeting in Mumbai. In their meetings in Ahmedabad, the judiciary fraternity made it clear that there was no conspiracy on the part of the opposition; the conspiracy was by the Prime minister herself. Her conspiracy was to put opposition leaders in jail and put the press under censorship. The emergency was announced to deprive the people of India of their civil liberties (Noorani 1978). Mr Nathwani formed a committee of Lawyers for civil rights and organized a private meeting at Jinnah Hall. However, this meeting wasn’t appreciated by the authorities. The commissioner was refunded to permit to organize such conferences. The government passed a particular order under DIR, holding any public meeting where the current political condition or emergency was discussed. Although, Nathwani and other committee members asked for permission formally. However, it was refused. They filed a petition against it in Bombay High court. This case made history; 157 lawyers with Mr.N.A. Palakhiwala represented their case in the Bombay high court. The judges stated that such meetings could be continued, and the refusal orders were also quashed.

Although Mrs Gandhi has used all means to eliminate the dissent, any oppositional opinions against her, it makes us think hard about the core values of the Indian constitution and Indian democracy, which have always advocated persuasive, peaceful and constructive dissents. Dissent is essential in a democratic setup as well as in judicial decisions. The right to dissent is the essence of democracy by putting sensors on the press, not letting them express fearlessly. The consequences can be disastrous for democracy if it works in this setup. The purpose of censorship mentioned in the constitution states only three reasons to announce press censorship, and in none of them, the internal disturbance has been said. We should also analyze that the press is not only for spreading the propaganda against or for the government. The primary role is to disseminate necessary information. True democracy can only survive when the nation has a fearless press and independent judiciary. Yes, limits to all these liberties exist, and the censor should monitor these limits rather than limit the essence of democracy. Unfortunately, the prime minister could not register that there was no conspiracy against the nation. It was her power, her position, which was at a cost. To protect Mrs Gandhi, took such bold decisions ignoring the tragic outcomes for her and the nation. But one must think that in politics, the game of power is inevitable, at Nehru or Shastri, but why did only Mrs Gandhi do what she did. Indira always had a distinct style of doing things; it reflected her political career. Her emergency decision was not the first time she surprised the people. She had taken decisions even at times kneeling, humiliated and embarrassed but never stepped back. It can also be seen how she had a better political experience and exposure because of his father and being the only child. This boldness, silence and sheer determinants can be the traits of Pt. Nehru during her upbringing. Over the years, it was claimed that Indira was not an institution-builder; however, we could observe that she shared an excellent relationship with those who she considered worthy. Indira’s childhood was not as blissful because of politics and illness. She grew as a reserved, lonely but proud individual. Although, Indira’s two qualities that every individual should assimilate were the sheer determination to survive and the constant urge to rise to a challenge. These two traits define Indira maybe better from all those political instances. Mrs Gandhi, indeed, to survive announced emergency and silenced all critics against her; her determination to rise to a challenge made her put herself beyond the law and the nation.

References

Guha, Ramachandra. 2007. India After Gandhi. New York: Harper Collins Publisher.

Morris-Jones, W.H. 1975. “Whose Emergency – India’s or Indira’s?” The World Today 451.

Noorani, A.G. 1978. “The Judiciary And The Bar In India During The Emergency.” Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America 403.

Palmer, Norman D. 1976. “India in 1975: Democracy in Eclipse.” A Survey of Asia in 1975:Part II 98.

Paul, Subin. 2017. “When India was Indira”: Indian Express’s Coverage of the Emergency (1975-77).” Journalism History 201.

[1] Mrs. Gandhi address to the nation on 26th June,1975 where she announced that the president has proclaimed the emergency. This is nothing to Panic about.

[2]Indira Nehru Gandhi vs. Raj Narain AIR1975

[3] The Representation of People’s Act, 1951 – Mrs. Gandhi was found guilty under Section 134, Sub Section (1) of Section 123

[4] The Janata Front won 87 seats, and was the single largest pre-poll alliance party and united with Charan Singh’s Bhartiya Lok Dal, Swatantra Party, the Socialist Party of India of Raj Narain and George Fernandes, and the Bhartiya Jana Sangh (BJS) joined together, dissolving their separate identities

[5] Jayaprakash Narayan, famously known as JP or Lok Nayak in Hindi. He is also known as the ‘Hero of Quit India Movement”

[6] JP demanded electoral and educational reforms. In order to present his concrete stance, he appointed an Electoral

Reforms Committee. Although, this committee did not recommend alternative electoral system but gave a list of specific recommendations relating to the election procedure.

[7] AG Noorani, “Justice with a fine balance”, The Hindu, April 25,2008

[8] See https://www.deccanherald.com/author/ravi-visvesvaraya-sharada-prasad

[9] Maintaince of Internal Security Act, 1971

[10] Article 21 in The Constitution Of India 1949 Protection of life and personal liberty No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law. See CAD of 20August, 15 September, 16 September, 13 December and 15 December 1949; Part 1.

[11] Short Report on Detention Conditions in West Bengal Jails

[12] Short Report on Detention Conditions in West Bengal Jails

[13] Laxmi Narain, “Mahatma Gandhi as a Journalist,” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 42 (Spring 1965) 267-270

[14] S.S. Sen’s article “Constituitonal Storm in India” VRO(1974):33-43