India and the one China policy

We do not expect other countries, including China, to comment on the matters which are internal to India, just as India refrains from commenting on internal issues of other countries”. This statement by Indian MEA spokesman Raveesh Kumar after China termed bifurcation of J&K “unlawful” and “void” speaks volumes about Indian Foreign Policy. India has traditionally been known as a country which believes in the policy of non-interference;

One-China Policy is the policy of acknowledging that there is only one Chinese government as opposed to separate Chinese states. Further under this principle, countries also consider disputed territories of Tibet, Hong Kong and Xinjiang to be an inseparable part of mainland China.

Over the years, Chinese policies have had a deep impact on the domestic security concerns in India. In addition to that, as the profiles of both India and China rise as regional as well as global powers, India has tried to take the charge of balancing with the reverberations of Chinese power and influence. while India dealt with an indeterminate stance on whether to nod along a similar engagement policy with China. As has been rightfully mentioned, India has “a nuanced bilateral economic and political engagement with China, albeit with eyes wide open.”

Why reconsider

The One-China Policy has been New Delhi’s oldest standard to deal with the regional superpower. when it was the first non-communist/socialist country in Asia to recognise Chinese Communist Party (CCP) ruled mainland China as the legitimate Chinese Government. On this level, a proper understanding of India’s One-China Policy cannot be achieved by restricting it to only a policy that legitimises a single government, rather one that more broadly symbolises respect for territorial sovereignty and desire for mutual progress.

Despite New Delhi’s extraordinary efforts to maintain cordial ties with Beijing, the same has little been reciprocated in a similar spirit. China does not usually release any casualty figure on their side, and has not done the same even in the present case. The strategic aim of Beijing apparently was to send a strong message to New Delhi and desist Indian Army from constructing any infrastructure, which, over an ambiguous border, is favourable to China. Such an act again signifies how China’s expansionist tendencies overpower its respect for international principles.

History

Nehruvian Blunder

India’s relations with China can be defined in two phases- pre-1962 war and post-1962. One of the glaring mistakes of this policy was accepting Chinese authority over Tibet.

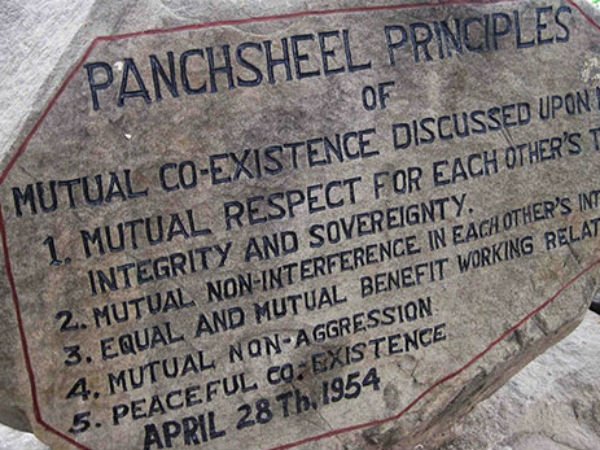

Till 1950, India and China shared no physical border, but China’s military invasion changed this equation forever. Tibet which has historically been culturally close to India looked up for help, but instead, India ended up signing the Panchsheel agreement with China, legitimising Chinese control. Even though India’s condition for providing asylum to him rested on his non-political stance while in the country, China was visibly displeased and this resulted, three years later, in the first Sino-Indian War of 1962. Nehru didn’t anticipate an aggressive attack from China and therefore Indian forces were taken by surprise, resulting in a quick victory for China.

The non-recognition of Tibet was the first diplomatic failure on part of the government. Apart from a short period in history, Tibet had never been under any Chinese rule. For almost two centuries, their relation was ambiguous on not on the similar lines, still, even when vaguely under China, they did not have its viceroy at Lhasa. and that the last voice in regard to Tibet should be the voice of the people of Tibet and of nobody else. In fact, within a book written by Nehru (Glimpses of World History), he projected an independent Tibet, lying outside and free from the Chinese empire.

Secondarily, such recognition of Tibet was extremely important for India’s security and major crowd within Indian had already recognised it. Thus it would have been in India’s prolonged interest to prevent the military occupation of the Tibetan plateau, and secure the region diplomatically.

Even on October 16, 1947, the Tibetans had sent a telegram to New Delhi asking for the return of certain territories. During those times, the border of Tibet, India, Nepal and Burma had not been properly delineated.

The Sino-Indian War of 1962

There had definitely been a diplomatic failure on part of Nehru to arrive at a solution with China. But the disputed borders were never delineated.

Further, questions are to be raised with respect to the strategic acumen that made India to finally take a decision of engaging in a “forward policy” – by the creation of military checks and posts throughout the disputed zones, that could not even have a proper supply; that China explicitly considered its own territory. Unsurprisingly, right upto the point when China attacked Indian positions in the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA, as Arunachal Pradesh was called then), Nehru and his defence minister V K Krishna Menon believed that China would not be taking any action. Unsurprisingly, China did attack.

The war changed India’s outlook towards China permanently and even though India largely maintained the policy of acknowledging “One-China” post 1962, it was now with much more skepticism and paranoia. After the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989, while the West came together to condemn China, India not only remained aloof but Rajiv Gandhi even went the distance to ensure minimum reporting of the issue. From invasion of Tibet to that of the Hong Kong extradition bill and even the Uighur Muslims controversy, India hasn’t stood up against China, even when the major democracies India holds ties with, did.

All these efforts have, however, not resulted in China reciprocating the same for India. China has increasingly been supportive of Pakistan and even supported its claims on PoK. China’s annexation of Aksai Chin clearly establishes its position on the principle of respect for mutual sovereignty. In furtherance of its claims on Tibet, China’s claims now also lie on the Tawang region in Arunachal Pradesh and parts of Ladakh.

Is it the right policy

India’s foreign policy, since the very beginning, has been defined by its characteristics of freedom and autonomy. Today, India can’t have official relations with entities that China considers as its territories, which limits India’s strategic options not only in the field of territorial, humanitarian and financial diplomacy but also defense planning.

The ceding of some of these rights in lieu of dedication to One China policy was done with the objective of achieving some definite dividends, including recognition of India’s territorial sovereignty and other diplomatic gains. Chinese support to Pakistan over PoK and construction of CPEC through the Aksai Chin area despite repeated objections at various international forums clearly shows how China has carried on its ignorance towards the “One India” policy. Its tactic of expansionism by not resolving border disputes is all too very clear.

Thus, there clearly exist shortcomings that demand a change, but how can reconsidering One China Policy help?

The way to do it

What the reconsideration of this policy and principle results into is largely defined by HOW it is done. While a direct overlooking of or confrontation with China is not an ideal solution, to support the various Autonomous and Special Administrative Regions, through political and diplomatic means might be a sound policy change.

Territorial Sovereignty

One of the major drawbacks in the current One China Policy is in the way which India’s territorial sovereignty has been treated.

India’s efforts to contain an aggressive China. In Tibet must start by strengthening the Tibetan Independence Movement. A region that has generated a lot of international attention and controversy due to Uighur Muslim majority exploitation, Xinjiang is also one of the most important strategic location for China, providing a clear gateway into Central and Western Asia and containing 4 out of 6 BRI megaprojects. India’s vocal support for this region can not only affirm its stance on the issue of Human Rights, India can also potentially dent the $46 Billion CPEC.

Defense and Security

The Sino-India war of 1962 and the Galwan faceoff now, both have clearly established that India’s border with China is a potential crisis awaiting.

Although China defines Taiwan as a rogue territory, Taiwan is much more. Even when India imports semiconductors, mobile phones or chips from China, it’s mostly Taiwanese firms having factories in mainland. India’s approach at such a time can be two-pronged, diversifying its trade by importing from Taiwan instead of China and providing a conducive environment for the setting up of businesses. Taiwan’s commitment towards India has been commendable and just days ago, Foxconn, a Taiwanese giant, manufactured the first batch of latest generation iPhones in India, while also suggesting to invest a further $1 Billion. A welcome change in India’s strategy has been depicted in its reaction against the draconian National Security Law in Hong Kong.

Financial Diplomacy

India-China bilateral trade amounted to $92.68 Billion in 2019 with a trade deficit of $56.77 Billion. A major part of this trade is made up of consumer electronics, metals and machinery, all of which can be replaced by Taiwan. India’s approach at such a time can be two-pronged, diversifying its trade by importing from Taiwan instead of China and providing a conducive environment for the setting up of businesses. Taiwan’s commitment towards India has been commendable and just days ago, Foxconn, a Taiwanese giant, manufactured the first batch of latest generation iPhones in India, while also suggesting to invest a further $1 Billion. At a time when Indian economy is suffering, India’s identity as a manufacturing hub won’t just bring in investment but also jobs.

Hong Kong is another key financial centre of the world with the highest concentration of banking institutions in the world. With bilateral trade amounting to $34 billion, India is Hong Kong’s third largest exporter. Beyond trade, recent years have also seen investment from Hong Kong growing steadily.

What changed with Modi

India’s moves in the Indian Ocean Region, although still short of major strategic utilisation, has been worked upon by Modi’s government. As the rounds of discussion trying to determine Beijing’s agitation towards New Delhi this year took place, one which was largely claimed by the experts in security and strategic affairs was – it’s a move to constraint India’s strategic attention, by not letting it expand to IOR, where Beijing’s vulnerability lies. Any move in the Indian Ocean Region could further be prong to mend the “deep psychological image deficit” produced by various incidents that led China with a perception of “being bested by India” – the Doklam compromise; Therefore, New Delhi, unsurprisingly, would consider the perception China wants it to establish of itself while employing any strategy.

India’s operations in Indo-Pacific are located in three institutions – the Quad; ASEAN and Western Indian Ocean Region (IOR). Further, it would bend the perception of India towards its outward- oriented strategy. All these moves very well switched the direction from India being confined by the virtue of China’s regional hegemony; India under Modi has refused to maintain the status quo of China’s postures translating into its final aim of securing land and power, and the start with IOR has been of the utmost importance to indicate New Delhi’s slight deviation from the One China Policy.

Posing a strong stance in the Maritime region can carry the weight of deviating from the One China policy in two ways – refusing the hard power upon which the State would thrive and project its power proportions; and acting as a pre-emptive measure towards the area that would be the prime target of retaliation, if New Delhi defies One China explicitly in the future.

Conclusion

As marked above, India’s “One China Policy” was not an active choice, rather a compromise executed to maintain a peaceful power balance in the Southern Asian dynamics and to set base for a lasting friendship. Even though there’s no denying China is not just a regional but an international superpower and India cannot afford to severe diplomatic ties, the current policy does need a revisit. While territorial integrity is undoubtedly China’s Achilles’ heel, it has been observed that China respects power and considers appeasement as a weakness. This might probably be the best period in decades for India to stand up to the occasion and revisit its One China policy.