Sectarian Biases – Challenging British India’s Colonial Legacy

15th August 1947 marked India’s independence from nearly two centuries of British Raj. Nehru’s ‘unity in diversity’ echoed India’s unique strength as a soon to be rising power in the international system. But despite the narrative of ‘unity in diversity’, sectarian politics and the divisive colonial legacy continues to impede India’s position as a regional power.

Since the very inception of empires and statehood, states have had a vested interest in acquiring and maintaining a monopoly of power and knowledge. Harold Innis, the famous communication theorist, has emphasized the impact of the state’s monopolization of knowledge in creating biases that shape our perception of reality. In Colonial India, the technologies of monopolization of knowledge by the British empire created inherently divisive and racist rhetoric towards Indians. From as early as the 18th century to the 20th century, nearly three generations of Indians grew up with the perception that their race was inferior and that Hinduism was always against Islam and vice versa. The British Empire’s divide and rule policy pitted Hindus against the Muslims and created sectarian divisions that were so ingrained that even to this day independent India functions with this divisive mindset.

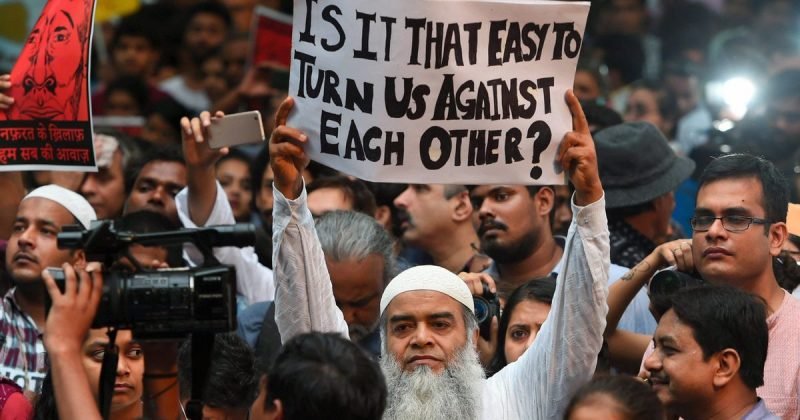

Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the fatuous divide between Hindus and Muslims has visibly worsened. The government has clamped down on freedom of speech and jailed journalists and political activists for speaking out against fascism, effectively creating an environment where dissidents are put into the same category as criminals.

This issue of censorship is not endemic to India. It can be seen in the Arab Spring and even in Cold War America’s careful depiction of anything remotely socialist as a threatening communist activity. This is a classic example of a government trying to create and capitalize off of biases already prevalent in the society (anti-Muslim, Hindu nationalism, etc.) by using political rhetoric that privileges one set of norms (Hindu nationalism) over others.

In this instance, it is important to acknowledge that the Bharatiya Janata Party is not alone in promoting sectarian biases. The assassination of Indira Gandhi and the subsequent anti-Sikh riots in 1984 still plague the Congress Party. The assassination, in essence, incited sectarian violence against the Sikhs as the Congress Party remained silent during the massacre and tried to play the victim.

While what is happening under the BJP is starkly different from the riots of 1984, it is impossible to not recognize the embedded role of religion in India’s electoral politics. British India had seen such an immense religious divide that coming out of this past has become a near-impossible endeavour. It is true that there is the widespread outcry over India’s seemingly sudden turn towards ‘Hindu fascism’, but a large part of India’s population still remains submissive to ultra-nationalism. Why is this?

For one, we can turn to Harold Innis and his extrapolation of the monopolization of knowledge by the state to how citizens perceive and respond to their social environments. The BJP has very intelligently capitalized over the accessibility of social media. Pioneering in the spread of disinformation over WhatsApp, the government has streamlined an environment where people can leisurely consume news designed strategically to benefit the Hindutva ideals of the party. A majority of Indians – specifically middle-class – get their bite-sized news from WhatsApp and rely on the app to shape their political views. The accessibility and social aspect of the app make it easier still to reproduce and share these views in different group chats.

This monopolization of knowledge and control over information on social media, when considered under the historical context of the colonial divide and rule policy, reveals why many Indians have become susceptible to anti-Muslim rhetoric. The fact of our reality is that the technology of governance in India has always thrived on a divisive and sectarian policy. It has been historically imbibed in us. The constant domestic sectarian turmoil impedes our ability to move forward in the international realm. Breaking away from the stringent colonial legacy of divide and rule is an important intellectual project. We should always contemplate and challenge the kind of patriotism we practice. Is it actually helping our country move forward or only compounding the problems British Raj left us with?