The Proliferation Security Initiative and the Legality of its Interdictions under the UNCLOS

Introduction

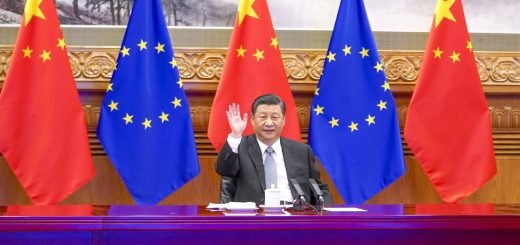

The Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) is an intergovernmental initiative which was established in 2003 by then President of the United States of America, George W. Bush, in 2003, to interdict the shipments of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) . Initially, 11 countries joined with the United States to shape and promote the initiative which includes Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom. It has now grown to be endorsed by a total of 107 countries which have publicly committed to the initiative. Membership in PSI only requires a state to endorse the PSI “Statement of Interdiction Principles”, a non-binding document that lays out the framework for PSI activities. Despite the support of over half the members of the United Nations, the initiative has received opposition from India, China and Indonesia of which China, despite being courted by the US to join the regime, turned it down citing concerns about the legality of interdictions.

Origin of PSI

The motivation behind the PSI was known to be the So San case in which Spanish and US forces cooperated in stopping and seizing a Cambodian registered vessel sailing in international waters off the Yemeni coast. The vessel was carrying missile parts and chemicals from North Korea to Yemen. It emerged that there was no basis in international law for seizure of the vessel or its cargo and it was released and allowed to continue to its destination. The seizure and subsequent release of the So San preceded only by days the release of the administration’s National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction, in which the U.S. government promised an aggressive approach to halt WMD proliferation. Since international law did not allow them to confiscate the vessel, in order to remove this gap in international law, several months later, President George W. Bush along with his counterpart, Polish President Aleksander Kwaśniewski, announced the Proliferation Security Initiative at Wawel Castle, in Kraków, Poland on May 31, 2003. The initiative was seemingly designed to make it costlier and riskier for proliferators to acquire the weapons or materials they seek. Ironically, even though the So San episode was crucial to the formulation of PSI, the existence of PSI would have done nothing to change the final outcome, and if another So san episode was to occur again, the United States would still be bound by international law to release the vessel.

Around the same time, the US was informed of North Korea’s efforts to pursue an alternative to plutonium production by purchasing individual components from foreign suppliers to accelerate its Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) program in order to supply fissile material for nuclear proliferation. North Korea’s efforts were subject to a 1994 US-North Korean agreement known as the Agreed Framework, which halted the production of plutonium for nuclear proliferation. The US policymakers understanding well that a formal and direct condemnation of Pyongyang’s effort would call upon dissatisfaction from US allies highlighted that the PSI’s efforts would extend to curbing proliferation activities of “countries of proliferation concern and non-state actors with particular reference to North Korea and Iran”

PSI is limited to stopping shipments of WMD and dual-use goods or items that have both civilian and peaceful purposes and that can be used to make weapons to those countries and non-state actors viewed as threats by PSI participants. According to the Arms Control Association, then Undersecretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, John Bolton, indicated in November 2003 that participants will not be targeting the trade of countries perceived as U.S. allies or friends, such as India, Israel, and Pakistan-all three of which possess WMD arsenals, including nuclear weapons. These are among some of the major effort undertaken by the US to increase the credibility of PSI as its legality has been a controversial issue ever since its inception.

The legality of PSI and its incompatibility with the UNCLOS

The member states of PSI has explained in a press statement that PSI “is an activity and not an organization”, thus understating the concept of membership in the initiative. It is believed that the question of the legality of the PSI is complicated as PSI contemplated interdictions in a wide range of locations from airports and harbours to territorial waters and the high seas. But since the PSI has been making efforts to justify interdiction of vessels carrying WMDs and related items, it has not been making any efforts in making the activity of procuring and transfer of such items illegal. Neither has the Article 19 of the UNCLOS, termed the transportation or procurement of WMDs as illegal as far as the innocent passage was concerned. Even Article 23 states that:

“Foreign nuclear-powered ships and ships carrying nuclear or other inherently dangerous or noxious substances shall, when exercising the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea, carry documents and observe special precautionary measures established for such ships by international agreements.”

This article is said to be a US-led compromise with the nations that wanted the Convention to state explicitly carriage of nuclear weapons in foreign territorial seas to be non-innocent. However, Article 110 of UNCLOS limit interdiction of vessels engaged only in the following activities:

(a) the ship is engaged in piracy;

(b) the ship is engaged in the slave trade;

(c) the ship is engaged in unauthorized broadcasting and the flag State of the warship has jurisdiction under article 109;

(d) the ship is without nationality; or

(e) though flying a foreign flag or refusing to show its flag, the ship is, in reality, of the same nationality as the warship.

In the absence of an objectively verifiable law on the possession and transfer of WMD-related items, the extent to which PSI interdictions can legally take place, given that international law prohibited such interdiction on the high seas without consent or in the limited circumstances envisaged in Article 110, is debatable.

An attempt by PSI core members to work within existing legal authorities was through draft amendments to the International Maritime Organization’s Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA). The SUA Convention, which entered into force in 1992, “addresses physical threats to ships and requires states-parties to take appropriate punitive measures against offenders”. The United States under the aegis of PSI, in an attempt to amend the SUA Convention’s Article 3 to expand the series of offences against naval vessels covered under the convention, introduced a series of proposals in October 2005; offences were slated to include a specific reference to the maritime transport of WMDs for the purpose of terrorist attacks, as well as broader language encompassing the maritime transport of WMD or related components, including dual-use items. Thus the 2005 Protocol to the SUA Convention was adopted by the IMO on 14 October 2005. The Protocol however entered into force only on 28 July 2010 and has only been ratified by 22 parties, most of who are not major maritime players.

PSI members have not yet established an international organization or even an informal secretariat to help carry out its mandate, not yet adopting binding legal mandates or a charter to define its scope and mandate. The PSI core members have also remained vague in describing the types of shipments they are targeting, speaking only in general terms of nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons and delivery systems and related materials. One can only argue that PSI will be more effective at halting the trade of the materials and equipment necessary for nuclear proliferation than the removal of the actual weapons themselves.

Conclusion

The PSI can be viewed as a strained effort by the US to dictate its own terms in the global arena, making the world perceive its “genuine” efforts to enhance multilateral cooperation in interdiction efforts to curb nuclear proliferation. Risks of PSI, encouraging greater secrecy on the part of proliferators who might choose to use shippers that are unregulated or land routes that are difficult to trace, could make it easier for terrorists to interdict state to state shipments. The discriminatory aspect of PSI with its targeting of states and non-state actors of “proliferation concern” or “rogue states”, is another political concern, which in turn questions the long-term legitimacy of the initiative. The effectiveness of PSI would depend largely on the extent to which non- and counter-proliferation efforts are handled, the resolution of issues of possession of WMDs, and other proliferation activities. However, if the United States accedes to the UNCLOS, which it hasn’t yet, it would only increase US credibility and leadership in dealing with the threat to international peace and security posed by the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

References

“Proliferation Security Initiative”, Bureau of International Security and Non-Proliferation, U.S. Department of State, Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/proliferation-security-initiative/

“The Proliferation Security Initiative: Is it Legal? Are we more secure?”, Independent Thinking on International Affairs, Chatham House, Retrieved from https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/International%20Law/ilp250205.pdf

Article 110, United Nations Convention on the Law of Seas (UNCLOS), Retrieved from https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

Article 23, United Nations Convention on the Law of Seas (UNCLOS), Retrieved from https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

Hamid, Adbul Ghafur and Win, Kyaw Hla, “Assessing the Viability of the 2005 Protocol to the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation”, Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 2012, Retrived from http://www.ajbasweb.com/old/ajbas/2012/Special%20oct/137-144.pdf

Joseph, Jofi,“The Proliferation Security Initiative: Can Interdiction Stop Proliferation?”, Arma Control Association, Retrieved from https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2004-06/features/proliferation-security-initiative-interdiction-stop-proliferation

Malirsch, Maximilian and Prill, Florian, (2007 “The Proliferation Security Initiative and the 2005 Protocol to the SUA Convention”, ZaöRV 67 , Retrieved from https://www.zaoerv.de/67_2007/67_2007_1_b_229_240.pdf

Tokimaa, Yokoi, (2008)“The Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) : The Compability with UNCLOS and the 2005 SUA Convention – The Way Forward in the East Asian Region”, The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University, World Maritime University, Retrieved from https://commons.wmu.se/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1092&context=all_dissertations

UN Security Council Resolution 1540 (2004), Office for Disarmament Affairs, United Nations, Retrieved fromhttps://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/sc1540/

von Heinegg, Wolff, Heintschel, “The Proliferation Security Initiative: Security v/s Freedom of Navigation”, International Law Challenges: Homeland Security and Combating Terrorism, International Law Studies – Volume 81, Retrieved from https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1246&context=ils

Wikipedia contributors, (3 Oct. 2019 )“Proliferation Security Initiative”, Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia, Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:CiteThisPage&page=Proliferation_Security_Initiative&id=919470023