Pakistan at a Crucial Juncture in its History

Pakistan, a nuclear state, is at a crucial juncture in a history marked by internal divisions and economic malaise. What happens next will have major implications for the South Asian state of 220 million people.

The nature of divisions shaping Pakistan today is different from the past when ethnicity played a significant role. The secession of East Pakistan as Bangladesh in 1971 and similar voices being heard in Balochistan and Sindh since the 1970s had been significant in determining the trajectory of Pakistan’s politics and identity. The current divisions, however, are primarily ideational, closely resembling the divisions observed in the United States since the Trump presidency. In Pakistan, signs of division were present to some degree since 2009-10 and got stronger when the Pakistan Tehrek-e-Insaf (PTI) led by former cricketer-turned-politician secured control of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) in the 2013 elections. But these divisions sharpened during Imran Khan’s tenure as the prime minister of Pakistan (2018-2022) and assumed alarming significance since his removal from power through a vote of no confidence on 10 April 2022.

The coalition government comprising of Pakistan Muslim League led by Nawaz Sharif (PML-N), Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM), and other parties that had previously supported Imran Khan as prime minister has been openly criticised by him in what could be labelled as a narrative of defiance. In a series of public rallies that are well managed and choreographed, Imran Khan has presented himself as the antithesis of the corrupt thieves who had aligned with the United States to usurp power. The United States, Imran Khan has consistently maintained, could not tolerate an independent foreign policy being pursued during his regime (such as improving links with Russia), and had conspired to bring “an imported regime” in the form of the coalition government. Supported by the media, judiciary, and others, this regime of “fascists” was, therefore, serving US interests in what resembled continued colonisation.

Presenting himself as the successor of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who fought and secured independence for Pakistan from British imperialists in 1947, Imran Khan has issued a clarion call to Pakistani youth, who comprise 60 percent of the total population, and other enlightened Pakistanis domestically and overseas to join him in another nationalist struggle. Identifying himself as an honest, reliable, trustworthy, incorruptible, and assertive Muslim, he promises Pakistanis the goal of true independence (haqiqi azadi).

Imran Khan’s narrative of defiance and vociferous, often derogatory criticism of the coalition government is not backed up with a clear pathway for his followers. Beyond the externalisation of the enemy (the US) and demands for early elections, in which he is convinced of securing a two-thirds majority, Imran Khan has not urged, for example, the youth to be more conscientious, hardworking, and committed to making their full contribution to making Pakistan strong. On the contrary, occasionally he minimises the importance of petty crimes while criticising the “robbers” ruling Pakistan. Irrespective of this lacunae, Imran Khan’s message, communicated in face-to-face and online spaces attended by thousands, and has secured him the status of a “true leader” resembling the popularity enjoyed by former Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in the 1960s.

The coalition government has crafted its narrative. Refuting the US conspiracy claims, it portrays Imran Khan as an incompetent, arrogant, self-serving individual surrounded by a coterie of sycophants, who was “selected” by the military to assume control in 2018 but was replaced due to his mismanagement of the economy. He is accused of mortgaging Pakistan’s sovereignty to the International Monetary Fund before being removed. His claims of being an honest person are also refuted. The “toshakhana” case filed against him accuses him of concealing his assets before the Election Commission of Pakistan while he was serving as the prime minister. The coalition government also claims responsible governance marked by tough decisions to raise energy and petroleum prices in the country.

This narrative, communicated by Maryam Nawaz (daughter of former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif) and others in large gatherings, has not caught the imagination of the youth in the same manner as Imran Khan. But there is sufficient support for this alternative narrative that finds expression in heated exchanges on social media between the supporters of PTI and the regime. Like in the United States, each side is convinced of the authenticity and veracity of its position and uncritically rejects the opposite viewpoint.

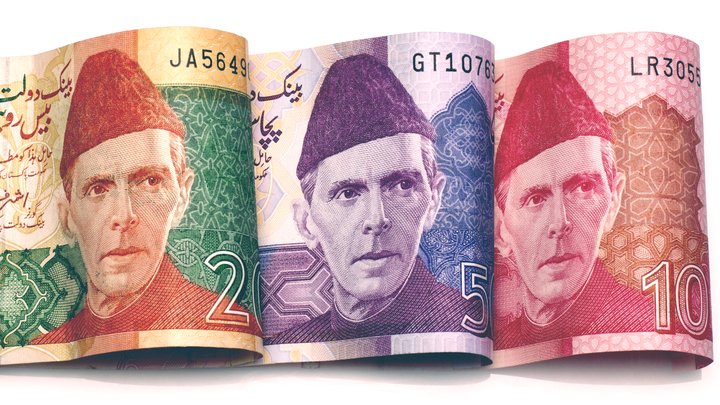

The political divisions have impacted the economy, which has registered a sharp decline. Consumer Price Index (CPI) growth increased from 13.4 percent in April 2022 to 24.9 percent in July 2022, causing hardship for both lower- and middle-income groups. The situation is not helped by Imran Khan suggesting that Pakistan, like Sri Lanka, may default. The exchange rate with the US dollar has declined from Rs170 in early 2022 to over Rs210 in July. There is also anecdotal evidence of people moving their assets out of Pakistan.

The most concerning development, however, relates to the increased anti-military sentiments in Pakistan that have directly or indirectly shaped the political landscape since 1947. The military had always been perceived as a united institution where hierarchy and strict discipline mattered, and which could not be publicly criticised. Only in February 2022 did Imran Khan’s regime declare criticism of state institutions, including the military and judiciary, a cognisable offence. But since his removal from power, Imran Khan has criticised the “neutrals,” a euphemism for the military, for meddling in politics and urged them to stand for what is just and right. His close associate, Shehbaz Gill, also made a statement on TV that implied a possible difference of opinion between the top brass and others in the military and was later arrested. Social media is also replete with comments that are categorically or implicitly critical of the military. A social media campaign identifies General Bajwa, the Chief of Army Staff, as a traitor responsible for Imran Khan’s removal from power further hinting at the separation between the leadership and the rest of the military.

This new trend does not bode well for the stability of the country at a stage when militants have increased their presence in Swat and adjacent areas. Failure of political leaders, including Imran Khan, to find a resolution to the current impasse could embroil Pakistan in an even more difficult situation than where it finds itself now.

This article was originally published by the Australian Institute of International Affairs