Semiconductor Diplomacy: The Emergence of a New Dimension in International Geopolitics of Disruptive Technologies

To emphasise the obvious, technology has an impact on geopolitics. Every day, fresh books and articles are published about how technology X may affect the politics of State Y. However, there are surprisingly few frameworks that describe precisely how technologies might boost or weaken national power. And to a larger extent, because of technology, the world was Europeanized in the nineteenth century. It was Americanized in the twentieth century. It is now being Asianized and far more quickly than you might think. Asia’s ascent has been rapid. The region, which is home to more than half of the world’s population, has risen from low to middle-income status in a single generation. By 2040, it is expected to create more than half of the global GDP and contribute to about 40% of global consumption.

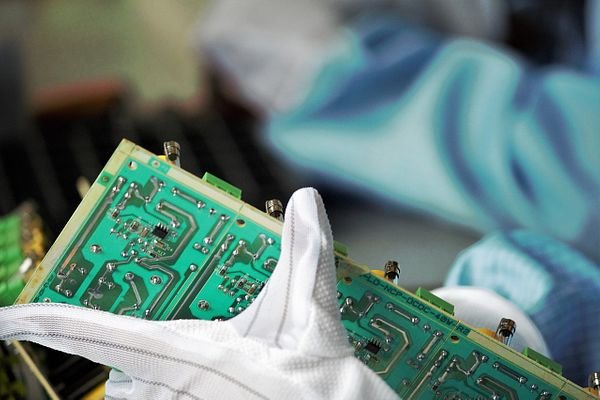

Interestingly, Asia is also the major hub of the global semiconductor supply chain and the place where you’ll find rare earth metals, which have come to dominate current geopolitics. Semiconductor chips and rare earth are both critical supply chains that drive the high-tech industry, and both are under scrutiny by governments attempting to shore up supplies for reasons of national security. Rare earths are a collection of 17 metals that are essential in the production of high-tech products. They are crucial because, without them, practically all of our lives would come to a halt because they are needed in a variety of items such as mobile phones, cars, aeroplanes, missiles, radars, and so on. At the same time, semiconductors are a significant part of our lives due to their function in the creation of electronic gadgets. Consider a world without electrical devices. Smartphones, radios, televisions, computers, video games, and advanced medical diagnostic devices would not exist!

However, when we discuss the nice to have vs. the need to have technologies, the supply concerns of semiconductors – the “DNA of technology,” as a recent U.S. supply chain analysis called it – are becoming a greater threat to national security. While Indians were busy with discussions about Ford’s closing its operations in India, What we Indians have missed out on is this: Automobile businesses all over the world are struggling to stay in business. After a spike in auto costs due to a lack of computer chips in the spring.

Interestingly, the United States’ policy on the intimately intertwined issues of China and semiconductors has changed rapidly in recent months. The current scarcity of semiconductors has convinced the United States that it is overly reliant on foreign manufacturing for its domestic semiconductor needs, posing a challenge not only to commercial activity but also to national defence. To address this issue, India and Taiwan are negotiating an investment pact to bring chip production to South Asia, as well as tariff reductions on semiconductor components by the end of this year. Surprisingly, this deal comes at a time when world democracies are strengthening economic and military links to counter an increasingly assertive China. China is aggressively attempting to increase its chip manufacturing and exports.

Nonetheless, everyone in China understands that innovation is the key to the Chinese economy’s future success. But this hasn’t always been the case. The manufacturing miracle that has unfolded in China over the last half-century, during which some 700 million people have been raised—or lifted themselves—out of dire poverty, was not driven by innovation. While China is a world leader in several fields, it continues to lag behind South Korea and Taiwan in semiconductors. Only two companies, South Korea’s Samsung and Taiwan’s TSMC, are currently mass-producing semiconductors at the most sophisticated process nodes. This has been a cause of worry for the government, which declared semiconductor self-sufficiency a priority in both its 13th and 14th Five-Year Plans. China has increased output but will still buy more than $300 billion of semiconductors in 2020. China will continue to make huge investments in semiconductor R & D and manufacturing over the next five years. We need to understand China’s technology sector has reached a critical mass of expertise, talent, and financial strength, which might reshape the global technology industry’s power structure shortly.

Bringing the discussion back to where it all began, semiconductors are a disruptive technology that is the emergence of a new dimension in international geopolitics. We must recognise that in today’s world, reliance on any country for “core technology” is a highly problematic situation for the entire globe. It allows for the formation of monopolies, which can cripple a country’s economy and, as a result, undermine national security. In this context, COVID has accelerated the trend of diversifying China-centric supply chains, but China’s manufacturing prowess and local market necessitate a balanced approach. The expression “China + 1” encapsulates the technique that several multinational manufacturers are employing to diversify and resilience their supply chains by shifting some Chinese-based sourcing to other nations.

Manufacturing activity diversification is a major driver of 2021, and it will improve supply chain resilience. India could be an option, but competition is fierce, particularly from Southeast Asian countries. This is very much evident in the fact that as firms look for another centre of production or distribution, certain Asian governments have put forward initiatives to attract foreign investment. Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam, for example, have implemented favourable rules for foreign corporations investing in their respective countries.

Supply chain regulation can be a powerful weapon for protecting a country’s resilience against unforeseen disruptions in trade, investment, and skilled labour supply. Its usefulness, though, may erode if geopolitics, rather than economics, becomes the primary goal. At the same time, developments in semiconductor technology during the past 50 years have made electronic devices smaller, faster, and more reliable. However, unfortunately, the 21st Century is not about liberal, optimistic geopolitics and it is unwise to think nations will not leverage what they’re pioneers at to fuel their strategic interests in the contemporary world. As a result, it becomes critical for India to grow in the semiconductor sector, as India is a net importer of semiconductors and despite high border tensions in Ladakh in June, India bought nearly 40% of total electronics from China in 2020.