Interview: An impassable road between Rome and Beijing

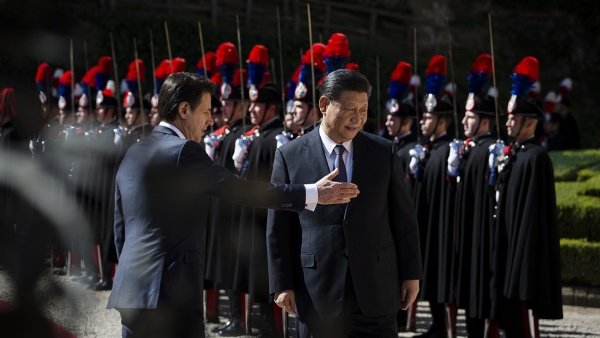

Chinese President Xi Jinping just returned from a visit to Europe to promote the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s unprecedented plan to expand its geopolitical reach. As Rome and Beijing signed a major deal on the BRI, several European leaders expressed alarm about the agreement’s ability to divide Europe.

The Kootneeti’s Geopolitical Analyst Melanie Romaro speaks with Maj Gen Rajiv Narayanan, AVSM, VSM – A Distinguished Fellow at United Service Institute (USI) and Former ADGMO Indian Armed Forces, on a wide range of issues revolving around this new era of Rome-Beijing ties

Italy became the first G-7 member to sign BRI deal. What are the possibilities that it will help Rome shaping its economy?

Italy is facing a severe economic downturn, suffering its third recession in a decade thanks to a decelerating growth rate tending below one

percent . It is under this bleak economic backdrop that Italy has agreed to join the BRI in the hope of some major financial infusion. It hopes to tap the vast Chinese markets and give a boost to its economy. Currently, its trade deficit with China is around Euro 16 billion (13 billion exports versus 29 billion imports), though the volume of trade is rather small.What Italy in its exuberance has failed to vector in, is the fact that the Chinese economy is dependent more on exports than internal consumption (70-80% exports versus 20-30% internal consumption). The BRI is more to do with China’s attempt to gain influence and recover its NPAs of its banks and financial institutions and gain profits to its SOEs by deploying their over-capacities.

The geo-economic interests of Italy and China do not match. Italy may find its economy faring much worse than before if it is not careful.

As we already observed small island nations and few of the African nations plunged into huge Chinese debt. What could be the consequences for Italy?

With the BRI, Italy could become the first G-7 nation to plunge into Chinese debt unless it is very careful of what contracts it signs. The memorandum of understanding signed during Xi Jinping’s visit on 22-24 March 2019 paves the way for Chinese investments in Italy’s infrastructure, energy, aviation and telecom sectors.

The BRI has more to do with utilising China’s over capacities in men, material, and products. The funding is via two state-owned financial institutions – China Development Bank & Export-Import Bank of China, four state-owned banks – Industrial & Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank Corporation, Bank of China & Agricultural Bank of China, and the state-owned Silk Road Fund. These institutions lend at commercial rates with a debt-equity swap clause. It is aimed at recouping their NPAs, financial health of the SOEs, who are allotted these projects, and the spread of Renminbi as an International trade currency.

The financial health of these institutions suffered heavily when China went on an infrastructure building spree post the 2008 economic collapse of the West, which impacted its exports drastically. The over capacities built up were deployed internally to keep the GDP growth rate artificially high in double digits. Having

raked up enormous NPAs and extremely high debt-to-GDP ratio, the BRI seems to be their panacea to recoup these losses quickly.The financial burden on the recipient country is enormous leading to a debt crisis. This leads to a geo-economic squeeze for a debt-equity swap and gaining sovereign control of a strategic asset of the recipient country. Hambantota and Gwadar are the prime examples of Chinese mercantilism. Italy would, therefore, need to be very careful to avoid such a trap.

Despite western pressure, Italy is preparing to sign BRI deal with China. Can this play any role in shaping a new order of relations in Europe?

Italy is likely to face major hurdles from the EU and USA since this agreement is perceived to give a likely back-door entry into the EU common market to China. Further, China’s entry into the aviation, energy and telecom sectors may lead to major security concerns within the EU and NATO. It may be because of these concerns that Italy agreed to only sign a ‘non-binding’ protocol, rather than any ‘legal’ agreements.

With a push-back emerging to its 16+1 architecture for dealing with Central & Eastern European Countries, via the Continental Corridor of the Silk Route, China would be keen to utilise Italy via its Maritime Silk Route for an alternate route to the Eastern European Countries, especially the Non-EU countries of 16+1. Italy at some stage would have to choose between the

EU and China. Should it choose the latter, it may find itself removed from both the EU and NATO, something it may not desire. Hence, to repeat, Italy needs to be very careful of the steps it takes in its dealings with China under BRI, especially read and understand the implications of the fine print before signing any contracts.

The US has publicly criticised Italy’s this move. How to see this move? Where should India stand?

The US has a major cause to worry about. In its N

ational Security Strategy of December 2017 and the National Defence Strategy of 2018, China (along with Russia) has been enunciated as its competitor. Even as it envisions fortifying the Trans-Atlantis NATO alliance, it finds that a founding member of the NATO is joining hands with the competitor.The key concern would be the agreement for Chinese investments in aviation, telecom and infrastructure sectors. Italy is a key partner in the US-EU defence industry and a leak of the latest technology to China would be one of the prime concerns. The USA has often accused China of stealing industrial secrets.

India needs to be very careful of its dealings with Italy in its high-tech and defence industry.

In a report, it says that the Vatican is positive about China, can it lead towards re-establishment of relations between both ignoring the fact of Beijing’s restriction on Chinese Churches?

There are no formal relations between the Holy See and PRC since 1951 when a priest of its legation in Beijing was arrested and executed over a trumped up charge of ‘attempt on the life of Chairman Mao’. Ever since it has maintained a legation in Taiwan. China, later unilaterally started appointing bishops to its selected churches, pushing many Catholic Churches underground for fear of reprisals.

China has long demanded that the Vatican endorse the ‘One-China’ policy and not interfere in the religious affairs on mainland China. The Holy See has de facto acceded to the ‘One-China’ Policy since it downgraded its legation in Taiwan to the level of ‘Charge de

Affaires ’, post-UN recognition of PRC in the 70s.In a major thawing of relations, post many back-channel talks, China and the Vatican signed an agreement on 22 September 2018 allowing the Pope to appoint or veto the bishops approved by the CCP. The agreement also does not signify reestablishment of formal diplomatic ties between the Holy See and China.

It seems that China may have agreed for the deal, more for the Vatican to present it in a positive picture thereby enabling it to get the Italians on board the BRI. Despite the agreement, the prosecution of Catholics in China, who see the Pope as their temporal ruler, continues unabated. These are looked upon by China as ‘underground prelates’, who consider themselves answerable only to Rome.

The deal signed by the Vatican is silent on their future. It is unlikely that the diplomatic relations would get re-established any time soon since it is hinged on the future of these underground churches and prelates, vis-à-vis the bishops approved by the CCP and now being appointed by the Pope.

Ports of Trieste and Genoa are key strategic ports in the Mediterranean from both geopolitical and geo-economic perspective. What will be the immediate effects of this on the region?

As per the Financial Times report of 12 January 2017, ‘How China Rules the Waves’, nearly two-thirds of the World’s top 50 container ports had major Chinese investments. These ports handled 67% of the global container volumes: of the top 10 ports worldwide, Chinese companies handled 39% of all volumes. Further, within Europe, the top 10 ports by container volume – Rotterdam, Antwerp, Hamburg, Bremerhaven, Felixstowe (UK), Algeciras (Spain), Valencia, Gioia Tauro (Italy), Piraeus (Greece), and Le Havre, all have major Chinese investments. The China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) is a major stakeholder at Piraeus wherein it controls two of its three terminals. Having invested billions of US$ to control and rule the International Maritime ports, Italy needs to question, why does China now want to invest billions in the Maritime Silk Route that does not correspond to International Shipping lanes?

China plans to use Piraeus for its outreach to Western Balkans, Central and Northern Europe. Towards that end, it signed a trilateral agreement in 2015 with Serbia and Hungary to connect Belgrade and Budapest with a high-speed railway line (renovating the old Orient Express alignment). While it remains stalled in Hungary due to EU investigation, work has commenced in Serbia in 2017. Based on this plan, HP, Hyundai and Sony have expressed their keenness to open logistics centres in Piraeus for use as their primary distribution centre (shift from Rotterdam) for their shipments to Eastern and Central Europe.

But this can happen only if the railway line in Hungary is cleared by EU, which is highly unlikely given that the Chinese fundings are opaque and their projects are given only to their SOEs without any global tendering process. It is in this backdrop that the Chinese interests in Trieste and Genoa need to be analysed. Trieste, on the Northern edge of the Adriatic Sea, could provide China access to Central and Eastern Europe. Genoa, on the Mediterranean Sea, gives access to Western and northern Europe.

Being the founding member of the European Coal and Steel Commission, which has now evolved into the EU, and a founding member of NATO, it may not be easy for Italy to break with the Western, liberal International financial rules and norms and accept China’s unilateralism. Italy, while signing up for BRI, is expecting financial support from the AIIB. It should have known that AIIB has nothing to do with the BRI. China controls the funding through its financial institutions and banks and allocates projects to its SOEs, without any tendering process. It is meant to revive China’s economy and so the BRI finds itself endorsed in its Constitution.

Italy may find that it may have to choose between its relations with China under BRI and being a part of the European Common Market. The pangs of BREXIT and the rising voices in the

UK against it may temper the Italian Government’s current euphoria. They may find that the cost of losing the European Common Market and technology sharing in defence, aviation & telecom sectors maybe too high to pay for joining the BRI with China.