How Many More Alliances Will Be Required to Protect an Open and Free Indo-Pacific Provided China Remains the Dragon?

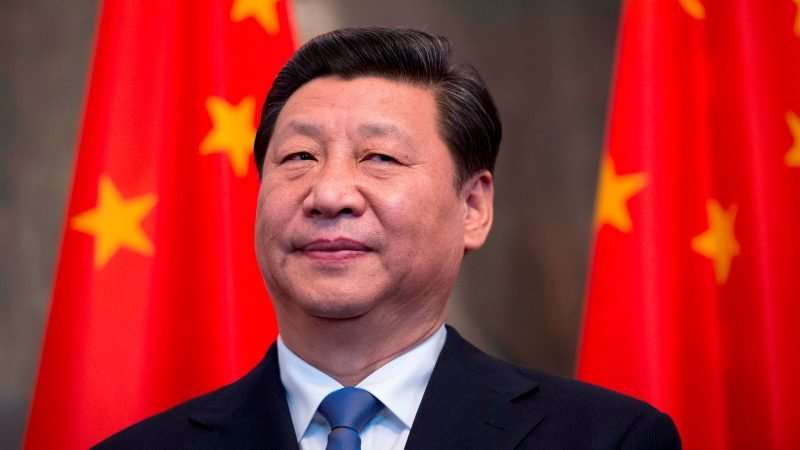

“The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history of more than 5,000 years, China has made indelible contributions to the progress of human civilization. After the Opium War of 1840, however, China was gradually reduced to a semi-colonial, semi-feudal society and suffered greater ravages than ever before. The country endured intense humiliation, the people were subjected to great pain, and the Chinese civilization was plunged into darkness. Since that time, national rejuvenation has been the greatest dream of the Chinese people and the Chinese nation.” – These were the statements made by Chinese President Xi Jinping during the Chinese Communist Party’s 100th anniversary from Beijing’s Tiananmen Square to party hardliners, Chinese masses, and the international community. The National Rejuvenation that Mr Xi talks about also has deep roots in China’s strategy of what it calls, the lost “Integral Chinese territory”.

During the Qing dynasty, the Chinese empire’s land expanded significantly, and the population increased from 150 million to 450 million. Many of the empire’s non-Chinese minorities were Sinicized, and an integrated national economy was developed. However, substantial parts of this expansionist empire went outside the control of the Chinese, which the CCP now plans to reclaim those lands. In the aftermath of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, the Qing Dynasty handed over the Taiwanese island, along with Penghu to the Imperial Japanese Empire; which today claims to be an independent nation-state. Similarly, the Qing rulers signed the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, ending the first Opium War but China paid an indemnity to the British, ceded Hong Kong territory, and promised to impose a “fair and reasonable” tariff. – This is the humiliating phase Mr Xi recalls in his speech at Tiananmen Square.

To understand how China plans to reclaim these lands what should we be looking at? Well, the term is called “Chinese Salami Slicing Strategy” and the Indo-Pacific security strategy has long been viewed as centred on the deployment of salami-slicing methods. This suggests a hungover Imperial China. It is a tactic in which the Chinese government is said to use minor provocations, none of which would constitute a serious offence in and of itself, but which, when combined, results in a much larger action or results in favour of China for territorial gains. This is very similar to the kind of politics Turkey is currently pursuing to acquire credibility over the Muslim world as the “true heir” of the fallen Ottoman Empire.

Despite all of the other concerns demanding China’s attention – the virus, its trade dispute with the US, Hong Kong’s national security law and a slew of economic woes – the South China Sea has been resurrected as a hotbed for serious tensions in recent times. For years, the South China Sea has been a hotspot, with various countries claiming sovereignty of its small islands and reefs, to access their resources. The South China Sea also contains critical maritime channels, that have been a point of contention. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, marine transport accounts for nearly 80% of world trade by volume and 70% by value. Sixty per cent of that cargo is carried through Asia, with the South China Sea handling an estimated one-third of this global shipping.

China has forcefully asserted sovereignty over the vast majority of the South China Sea under the so-called “nine-dash line.” The rising power has been encroaching on territory within the 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia; threatening military intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance activities in China’s EEZ; and protesting US Freedom of Navigation Operations and overflight operations near People’s Liberation Army (PLA) outposts far outside China’s EEZ. Beijing claims over 90% of the sea, which covers an area of approximately 3.5 million square kilometres. China has so far been able to assert its claims in the South China Sea citing the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) rules but it came as a blow to the Chinese communist leadership when The Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague decided against Chinese claims to rights in the South China Sea in 2016, supporting a case launched by the Philippines in 2013. The court said that China’s claims of historic rights within the nine-dash line, which Beijing uses to demarcate its claims in the South China Sea, lacked legal support.

Apart from the plain economic objectives, we must pay close attention to the Chinese geopolitical interests in the South China Sea. From a Chinese perspective, there are two major ones. First, the South China Sea is critical for the strategic patrol of Chinese SSBN [nuclear ballistic missile submarines], which is used to access the west Pacific Ocean to maintain nuclear deterrence against the US. Second, if the US initiates a military attack against mainland China the South China Sea will act as a buffer zone for China.

However, China’s aggression in the South China Sea seems to have caused significant issues for itself. It is proving to be more detrimental to Chinese interests in the region. What China’s approach has done by displaying aggression in the disputed sea is that it has provided a huge push for the major countries to come together collectively in confronting the Chinese in a location where they have historically wielded more influence. China’s interests are continually being called into question. Several Indo-Pacific states have significantly increased defence spending in the last decade to prepare for new threats; in certain cases, they have also sought more extended roles in building the regional security infrastructure. Some are looking to form new intra-Asian security alliances and strengthen current strategic alliances. Japan, Australia, and India are among the most active countries in this area.

Washington moved fast to upgrade the Quad communication with Australia, India, Japan, and the United States to the level of a leaders’ dialogue, reviving the dormant trilateral alliance. The US and its Indo-Pacific partners have declared their determination to expand collaboration beyond security – in areas like health, climate change, and technology, among others – to increase the collective potential to supply global and regional public goods.

Simultaneously, Whitehouse has expended substantial diplomatic resources in rallying its European and Indo-Pacific partners in support of a global agenda to confront China’s growing ambitions and influence. Importantly, because the Biden team sees competition with China as a long-term global challenge rather than a short-term regional imperative while defending the hasty pull-out from Afghanistan, Biden makes it clear that the United States 21st-century concerns are in the Indo-Pacific region. This agenda has prioritised coordinated pushback on issues such as Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, cyber malpractices, human rights violations, and techno-authoritarianism.

However, currently, the world sees Australia, New Zealand and United States Security Treaty (ANZUS), Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD), and most recently the AUKUS; a US, UK, Australia new trilateral alliance in the Indo-Pacific to counter China. Under AUKUS’s first major project, Australia would create a fleet of nuclear-powered submarines with the assistance of the United States and the United Kingdom, a capability targeted at fostering Indo-Pacific stability. Despite all of the cooperation to challenge China, China continues to be the dragon in the South Chinese Seas. As a result, we must ask, “How Many More Alliances Are Needed to Protect an Open and Free Indo-Pacific?” A major reason China continues to have the energy fight for its interest in seas is due to the reason these cooperative efforts have not been truly collective. This is evident as China is looking for a friendship with its European counterparts. Beijing intends to use Europe as a counterweight to the United States. While it is the reality of countries like India and Japan not joining any security alliance specifically designed to oppose the Chinese in order to avoid escalating border conflicts with the dragon owing to territorial proximity.

Whatever it is President Joe Biden of the United States will host the first in-person summit of leaders from the “QUAD” countries – Australia, India, Japan, and the United States – who have tried to strengthen cooperation to counter China’s growing aggression is in few days. If these leaders want to truly counter, they must start focusing more on security cooperation rather than just cooperation and get the European Union on board. Nevertheless, the first-ever physical meet to create an Open and Free Indo-Pacific sends strong signals to China and the world about the intentions of these groups on their collective geopolitical ambitions.