The Dragon’s Village: A Feminist Review of an Autobiographical Novel of Revolutionary China by Yuan-Tseng Chen

“Now, this is a grownup’s world for you, and it’s a man’s world”

These words were etched into my mind as I read Yuan-Tseng Chen’s autobiography which follows the life of Ling Ling, a teenage Chinese girl who went on an expedition as a cadre and toured several villages to implement the Farm Reforms. They were said by Ling’s aunt who advised Ling of the agony of the patriarchal world before Ling set out to volunteer in the Agrarian Revolution of China in 1951 which aimed to investigate feudal lords’ land deeds and re-distribute excess land to the poor peasants. Living a sheltered life with her aunt and uncle in Shanghai’s old and rich French Concession, Ling was brought up to ‘succeed’ in life by marrying well and bearing heirs. However, as a strong-willed city girl, she defies the restrictions and stays in China due to her curiosity, while her family departs for Hong Kong as Communist forces seize control. In this work, Chen focuses on bringing hidden realities about the revolution to light with the story arc of Ling and the rural women for whom the revolution proved to be a blessing.

“The story is fiction but true”

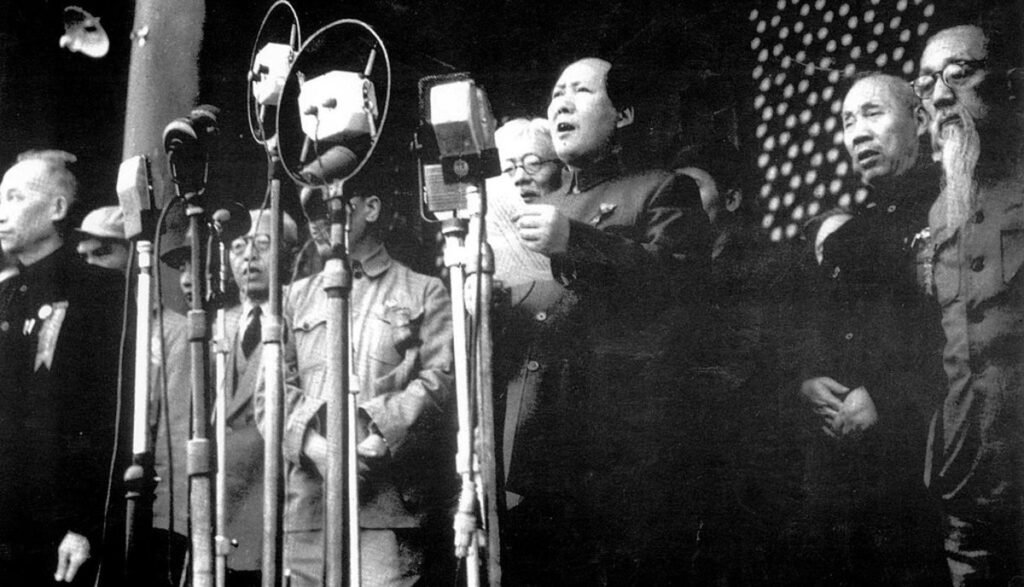

Chen wrote this book after moving to the United States in 1972 and indicates that it is a novel with a key representing real people doused in fictional history. Yuan-Tseng Chen narrates the story of her experiences in north-western China’s Gansu, penning them down into the form of her character Ling Ling, helping us peer an eye into the happenings of the Land Reform movement under Mao Zedong which involved the mass killing of landlords but led to women’s liberation from a masculine-centred society. Crudely building her story, Chen exposes the difficulties of women in the civil war in Chinese society during the era. Chen’s combination of fiction and reality helps the reader recognize the behaviour, culture, and traditions of China during the revolution that were passed down, making her writing style an exciting way to convey the realities that remained blurred under the cloud of half-truths.

“Peasant men did not look at women. When they talked to a woman, they looked at something straight ahead as if they were talking to some other man in the room”

Chen’s writing style has generated a tragic mood around the circumstances of women at many points, effectively demonstrating how women in Chinese culture suffered twice as much as men due to the pressure of a patriarchal society and feudal system. The dire picture created by Chen accentuates the need for reform in the lives of Chinese women that the reform was able to bring to some extent. Several illustrations in the novel indicate the dreadful condition of the women in Gansu but the novel falls short in drawing on Ling’s perception as a woman. Ling’s initial humanistic character failed to make a sonorous connection with the women of the village creating a disruption in her character which suddenly depicted her as a detached cadre without a transition. Similarly, while portraying the village women, Chen lacked a grace of depth which created shallow female characters who seem to judge each other on societal standards. Chen missed out on building deep characters that could have been developed to further enrich the plot and provide some notable strong female performers. One such character that Chen missed out on was the lady who carried secrets that the villagers couldn’t fathom named ‘Broken Shoe’.

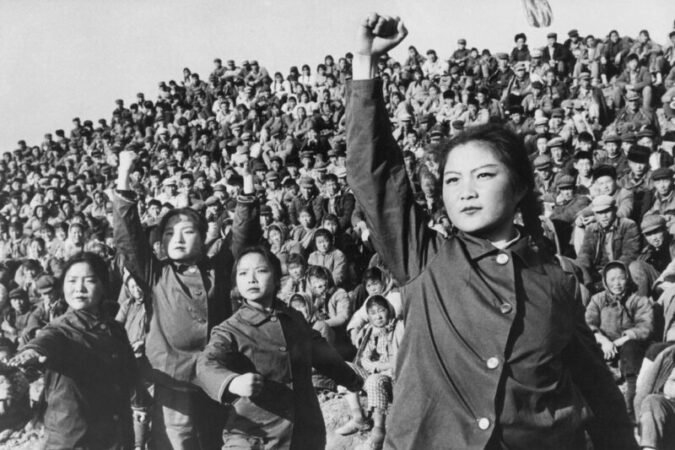

“You know, sometimes I wish I could be elected, but sometimes I don’t want to be. Even now, though I’m only an activist, the other women want me to do what they themselves would like to do if only they dared.”

Chen paints the reform as China’s first beckoning towards social upliftment of women, as she portrays an election happening in the village which Xiu-Ying, a young girl fights and wins. Ling’s story arc battles with cases of sexual assault, rape, murder, and female infanticide in the village as she struggles to fight the societal customs with the constitution provided by the communist forces. Fighting her inner desires for peace, support, and love, Ling was shown as a woman determined to see her end goal without the use of violence, but the brutish ignorance of the villagers brought out her new traits. It does make me wonder whether Ling was born apprehensive, or the rich Shanghai life subdued her fierceness out of her. However, Chen was able to show the turning point in Ling’s personality very effectively as she wrote: –

“But his stubborn defence, his continued efforts to picture himself as an ordinary landlord with ordinary sins enraged me. I moved towards him threateningly………Later I wondered at myself. It took this crisis to bring out traits within me that I didn’t even know existed”

The novel finally ends with triumph as the villagers burn the land deeds held by the feudal lords and Ling calls out to a village lady: –

“Da Niang, come and get your land. It’s time”

The poignant conclusion describes how, because of the reforms, women gained the right to own land and inherit property. The plot, while complex, was able to build a clear situation in my mind of the harrowing situation of Chinese women during the civil war and how reforms introduced a few Western concepts making life a bit easier for women. I believe it would make a good read for individuals interested in Gender Studies or Feminist Studies and for those looking for a personal and novel perspective on the Agrarian Reforms movement in China as Chen effectively draws on her experience to provide us with her notable work.