UN in Crutches

“In a world deluged by irrelevant information, clarity is power”- Yuval Noah Harari

Does this clarity come at a price? And if yes, what is the price for it and who shall bear the burden for the same? Human beings as a group have undergone many changes over centuries to apparently get this clarity and have somehow let go of continuity. This has led to people creating ancient identities for themselves by weaving the bold and the new into a single yarn. The whole of humankind constitutes a single civilization yet there is nationalistic isolation which doesn’t offer a real solution to the unprecedented problems of the global world. Benign patriotism has morphed into chauvinistic ultra-nationalism which has deluged the world with irrelevant information. Zealous nationalists should be asked whether their countries can by themselves, without a robust system of international cooperation, protect the world or even themselves. The answer to these questions can be quoted from Dag Hammarskjöld, the tragic second UN secretary general, who had it best. The United Nations, he said, “was created not to lead mankind to heaven but to save humanity from hell”.

The United Nations was founded during a period when the world had known almost nothing but war and strife, book-ended by its two savage World Wars that began within 25 years of each other. In the first half of the 20th century, people in most parts of the world scarcely had the luxury of deciding whether they were interested in world politics and world politics took a thoroughly intrusive interest in them. Horror succeeded in horror until in 1945 the world was brought face to face with the terrible tragedies brought by war, fascism, nuclear bombing and attempted genocide. Hiroshima and the Holocaust. Had things gone on like that, the future of the human race would have been bleak indeed. The kind of hell Hammarskjöld had in mind was not hard to imagine in the wake of world war and Hitler’s extermination camps, and with the atom bomb’s shadow spreading across the globe. How much of a part the UN played in holding nuclear armageddon at bay divides historians. But there is little doubt that in the life that has passed since it was set up in 1945 it helped save millions from other kinds of hell – from the deepest of poverty, from watching their children die of treatable diseases, from starvation and exposure as they fled wars made in the cauldron of ideological rivalries between Washington and Moscow but fought on battlefields in Africa and Asia.

Almost 70 years and half a trillion dollars later, the question arises has the United Nations achieved what it was formed for or is it still struggling? The United Nations is a response to a Hobbesian world, a world in which we have seen the horrors of the First and Second World Wars. The UN charter was the product of those who won that victory at the end of the Second World War, converting the war-time alliance into a peace-time organisation, and they saw the horrors and vowed never again. But their solution was not to create a single power to be a leviathan. It was to create a system of laws that would ensure that the world of the second half of the 20th century and indeed now, the world we have inherited in the 21st would be a better place than the one that had preceded the creation of the United Nations.

At a time when our security is seemingly under threat from every side “terrorists, disease, pollution, population growth, natural disasters, short-sighted foreign policies” we need to remind ourselves why the United Nations remains vital to international governance and why it warrants the world’s engagement, even as it needs renovating. We live in an era of historical amnesia and strategic myopia. Still, if there is one lesson from 9/11 that we should all be able to agree on, it is sure that there is no security in a gated community. In an interdependent world, engagement and cooperation, not isolation and unilateralism, are the keys to security. No country is an island in our globalising world, at least figuratively speaking, and international cooperation is indispensable.

A hundred years ago, the only effective protection against aggression was military capacity “your own and that of your allies”. The only checks on would-be aggressors were the costs of fighting and the risks of failing. The issue was not law, it was ambition and power. The alliances that emerged in the 19th century to deter aggression ultimately collapsed, and catastrophic conflicts followed. The world’s aspirations for the United Nations have exceeded the organisation’s grasp, but it has, nevertheless, served us reasonably well in the “intervening period” far better than its critics realise or admit. Certainly, the prevention of World War Three owed a lot to nuclear deterrence and collective defence through NATO. However, bloody as the world has been in the last 70 years, it would have been a much worse place without the UN. While the UN is often derided as a talk shop, “jaw, jaw” to paraphrase Churchill, is better than “war, war”.

The UN has given birth to concepts we now take for granted such as peace-keeping, which provided a buffer between protagonists so that the interstate wars that did break out did not reignite after the shooting stopped. The UN has helped East and West avoid a nuclear Armageddon by, inter alia, pioneering arms control treaties and verification, notably, the Non-Proliferation Treaty regime and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The UN has served as a midwife in the births of more than 100 countries since 1945, the great majority of which came into being peaceful. More broadly, the UN has helped the world to feed its hungry, shelter its dispossessed, minister to its sick and educate its children.

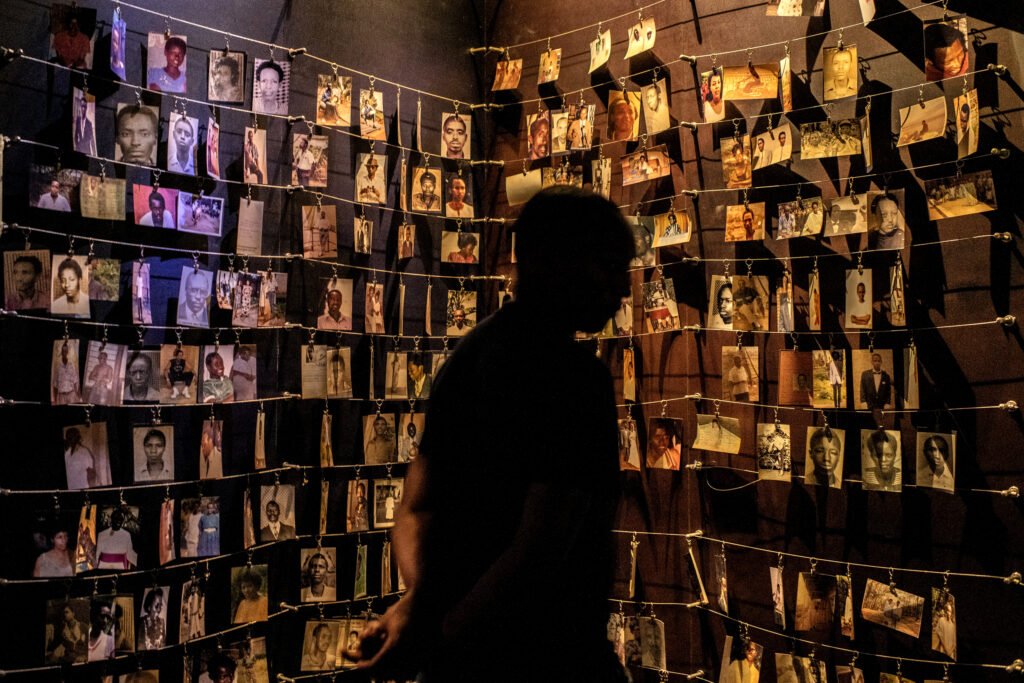

It is trite but true that if the UN did not exist we would have to invent it “if our generation could generate the political will and vision to do so”. In Rwanda, even as 800,000 people were being systematically slaughtered, the Security Council played legal word-games about genocide, preferring to talk of “acts of genocide”, and split ting hairs in order not to trigger the voluntarily accepted obligation under the Genocide Convention to intervene to stop the slaughter, while the “genocidaires” were literally, not figuratively, splitting heads. What prospects do ordinary people have when UN member states, especially its most powerful members, retreat into the complexities of sovereignty, ethnicity, religion, regional politics and economic interest and fail to act?

The UN’s failures, humanity’s failures, take many other forms. Poverty traps rob the poor of their potential in vast stretches of the world, while the unfulfilled promises of assistance by some donor countries and the graft of some host governments combine to preserve the tragic status quo. New issues arise, notably religious fundamentalism and the potentially catastrophic combination of terrorism and weapons of mass destruction which, rather than eliciting a coordinated response, tempt the powerful to go it alone and the weak to turn a blind eye, jeopardizing as they do so the very essence of collective security. Some governments are just plain oblivious to the UN’s weaknesses, or indifferent to them, trusting fate to fix them. Others would just forsake the UN altogether and look to their own strengths in a dangerous age. The first course would condemn the UN to an existence increasingly on the periphery of humanity’s vast needs. The second course would condemn the world to repeat history in infinitely more dangerous circumstances. It is just plain foolish to throw out the international rule book now. Now is the time, in a single superpower era, to reinforce the rules of the road and encourage the development of a culture of law, rather than myopically waiting for the rise of the next superpower and whatever claim to exceptionalism it makes.

The wiser course is to adapt to the UN, the institution our parents bequeathed to us so that it serves us better now and safeguards our children’s future. Legitimacy is a precious resource for the international community’s peace and security. This fundamental aim can be achieved with equal rights in state representation on the council. For a better United Nations, the council needs better credibility, legitimacy and equal representation for every nation, which the international community demands peace and security. Reforms have been an outstanding problem from the beginning, especially with the veto power system granted to the P5 member states. In this regard, as the saying goes: “Power corrupts, but absolute power corrupts absolutely.” In other words, the five police states enforce their ideas to protect their national interests. Also, these five policemen strive to maintain the world order while maintaining the status quo.

There is a dreadful old story about Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, and it is said that Adam, when he found that Eve was becoming a bit indifferent to him — Adam said to Eve, “Eve, is there someone else?” One can ask the same question about the United Nations – Is there another institution that brings together all the countries of the world to work together for common objectives in all our collective interests; there clearly is not. If the United Nations didn’t exist we would have had to invent it in the name of our common humanity. With all its defects albeit walking on crutches, the United Nations is the one place where we can actually work together to dream the same dreams together.