Barriers to India-EU Trade Relations

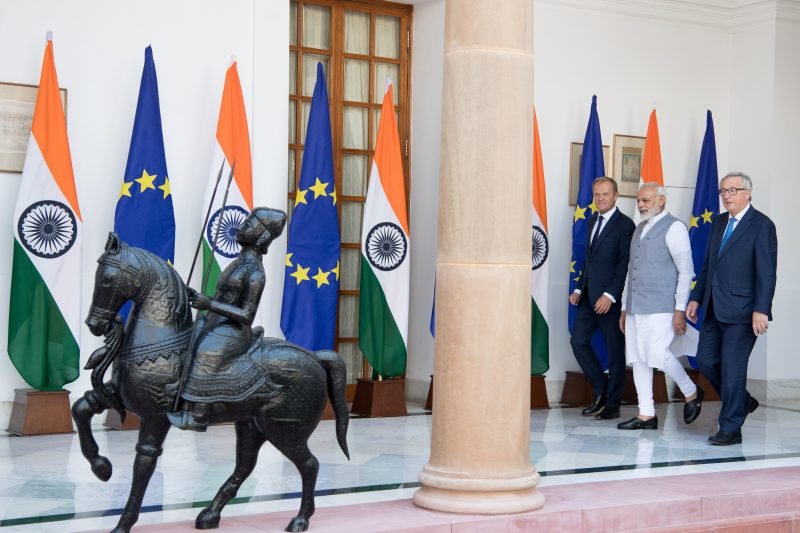

India and the European Union (EU) are considered as vital players in the global economic community but despite becoming strategic partners way back in 2004, relations between the two remains rather stagnant. Discussions on a broad-based Bilateral Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA) began in 2007 but have been stalled since 2013, owing to a lack of agreement on various contentious issues, such as tariff barriers and intellectual property rights (IPR). As with any free trade agreement, the BTIA aims to reduce barriers to trade, services, and investments and improve economic conditions for both India and the EU, whilst accommodating various safety measures their respective governments have put in place. Recently, during the India-EU summit, the two sides reviewed the India-EU Strategic Partnership: A Roadmap to 2025 and agreed to resume negotiations over BTIA and find a ‘balanced, ambitious, comprehensive and mutually beneficial trade agreement.’ Talks are set to recommence in June after the WTO ministerial meeting.

Brimming with potential

Most of the literature refers to the deadlocked India-EU trade relations as one of ‘untapped economic potential’ owing to the transformative capacity the partnership entails. Bilateral trade in goods was valued at €65.3 billion in 2020, accounting for 11.1% of total Indian trade. The EU is India’s third largest trading partner, whilst India was EU’s tenth largest trading partner. A significant proportion of EU’s exports to India includes, machinery and vehicles, chemicals, and other manufactured products, while India exports primarily organic chemicals, clothing, and iron and steel. Successful negotiations of the BTIA would be beneficial to the two trading partners, not only from an economic aspect but also from a geopolitical one. India is the world’s sixth largest economy and is in dire need to re-establish itself as a reliable economic and strategic partner in the Indo-Pacific, particularly since backing out of the RCEP. The EU, on the other hand, in the post-Brexit era, is looking for viable alternatives to China, whose bilateral trade with the EU is six times more than that between the EU and India. A strong partnership would be both compelling and beneficial to both parties as it acts as an opportunity to diversify trade as well as a means to balance China.

Contentious issues

There are several impediments to the agreement that have rendered it dormant. A major area of concern is the EU’s demand for a reduction in tariffs and enhanced access to India’s dairy, wine, and automotive sectors. The EU has a surplus of dairy products and exports high-value products, like ice cream, yogurt, and cheese. India’s dairy sector, despite being one of the largest in the world, is mainly comprised of small and marginal farmers. Opening up its markets to the competitive and highly subsidised EU market would have negative impacts on trade and livelihood in India. There are however, various companies in India that would prefer a reduction in tariffs, particularly those that use dairy as an ingredient in the processing stages, but this opinion forms the minority. Time and time again, the EU has called for reductions in the duties placed on wines and spirits as India represents a rising market for alcoholic beverages. Wines and spirits are not covered under GST, instead excise duties are levied by the state governments, thus forming a major source of their revenue. In India’s recent trade deal with Australia, duty on wines has been lowered from 150% to 25% over a ten-year period, suggesting that there may be some leeway for alcohol imported from the EU. Finally, the EU has emphasised their desire for India to commit to reduced duties on automobiles and automobile parts, citing a protectionist trend. This has the potential to remain as a bone of contention, as India’s automobile sector in 2016 contributed 7.2% to India’s GDP and provided jobs for 32 million people. In light of the pandemic, which caused a significant decline in exports, Make in India initiatives, and the presence of Indian, Japanese and Korean manufacturers, it is likely that this sector will be protected during the talks.

Agriculture products have historically been sensitive in India’s trade relations. According to a report made by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), the main challenge faced by India’s agricultural exports is in meeting the sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures imposed by the EU, which are relatively more stringent than international organisations, such as the Codex Alimentarius Commission. Rejection of Alphonso mangoes, infested with fruit fly, triggered the adoption of alternative agricultural practices by farmers in India, and now, mango pulp is a key export item to the EU. Similarly, Indian table grapes were denied entry at EU ports owing to greater than permissible quantities of chlormequat chloride (ccc), a chemical known to pose toxicity in humans, because the APEDA-approved laboratories did not test for ccc residues at that time. Upon installation of a residue monitoring protocol, India has advanced to becoming the largest exporter of grapes to the EU. Aside from this, India resorted to damage control when the EU decided to test up to 50% of shrimp consignments for antibiotics as opposed to the earlier 10%, upon detecting residues of banned antibiotics, chloramphenicol and nitrofurans, in some of the shipments. There have been instances however, when the EU raised the maximum residue level (MRL) for certain products to impractical standards. India had raised a specific-trade concern at the WTO when the EU lowered its MRL of ccc in grapes from 0.05mg/kg to 0.01mg/kg, without any scientific justification. Subsequently, the EU decided to maintain the MRL at 0.05mg/kg for grapes. This highlights that different products are subjected to different compliance testing and standards, and the absence of adequate information sharing, leads to huge losses in revenue, reduction in shelf-life of products, and food wastage. Taking into consideration that these policies are to ensure the health and safety of the consumer, the need of the hour for all stakeholders, is knowledge-sharing and collaboration with the EU. This includes the inclusion of equivalence agreements and mutual recognition agreements for specific products, incorporation of methods to strengthen supply chain infrastructures, particularly cold storage, and improvements to agricultural practices and food safety standards.

A major roadblock in negotiations is EU’s demand that India strengthen its IPR regime. Currently, India is signatory to the TRIPS agreement but the EU expects India to implement TRIPS-plus provisions, which includes increasing the term of patents beyond twenty years as well as data exclusivity. Adherence to EU’s demands would have detrimental effects on the Indian pharmaceutical industry, which provides cheaper generic versions of drugs, vastly improving public health. Presently, Indian legislation bans evergreening of patents and data exclusivity remains a controversial topic, both of which are foundational to Indian generics. A valid argument against strict forms of IPR is that it incentivises companies to focus on existing products and discourages the original company from producing newer and more beneficial technologies. Moreover, the Satwant Reddy Committee Report pointed out that under Article 39.3 of the TRIPS agreement, the provision extends to ‘data protection’ and not ‘data exclusivity,’ indicating that India is well within TRIPS obligations. Having said this, in the absence of a data exclusivity period, competitors are provided with the unfair advantage of having to avoid time-consuming and expensive safety and efficacy trials. It may be prudent for India to adopt limited measures of data exclusivity but this is likely to require extended deliberations. Improvements have been made to other aspects of IPR, including India’s assent to the Nice, Locarno, and Vienna WIPO agreements. Additionally, India ratified key ILO agreements in 2017, i.e. Convention 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labour and Convention 138 on the Minimum Age of Employment, thereby alleviating EU’s concerns about human rights violations.

Another wedge between the partners is trade in services. India’s demand to be given a ‘data-secure’ status by the EU hit a brick wall, owing to EU’s concerns about India’s approach to data privacy and protection. Lack of a data-secure status impedes cross-border supply of sensitive data, which is essential for services, like telemedicine, clinical research, and engineering design. It is anticipated that India’s Data Protection Bill will fulfil the EU’s concerns and meet global standards. Additionally, in order to liberalise services, India has sought greater access to Mode 4 under GATS, which includes hospitality, healthcare, and pharmaceutical sectors. Increased freedom of movement of English-speaking skilled professionals could facilitate flexible immigration norms but this is likely to be challenging as individual EU member states have varied immigration policies. The EU, on the other hand, prefers greater access to the Indian economy through Mode 3, in particular the retail, banking, and insurance sectors. This will require a considerable amount of political will in order to materialise. It has been opined, however, that India’s access to Mode 4 is likely to be dependent on its ability to meet EU’s demand for Mode 3.

Glimmer of hope

Despite the extraordinary delays in negotiating the BTIA, rapprochement of India and the EU is bound to lead to powerful economic ties that transcends the entire global community. There are several pathways where the interests of India and the EU can converge. Reduced tariffs for commodities, like wine and application of stringent SPS measures on agriculture products can be achieved through collaborative work between farmers and civil society organisations. Implementation of a Data Protection legislation in India would go a long way to cementing India’s role in the global digital scene. Ties can also be deepened on introducing a policy for talent-driven migration for Indian professionals. The recent India-EU summit suggests the possibility of a prosperous friendship and the BTIA provides a robust platform for bonding. There is immense potential for this partnership to transform and influence the global trade and development stage. Albeit, this can only arise if synergy, compromise, and flexibility are exhibited during these talks.