Prisoners of War

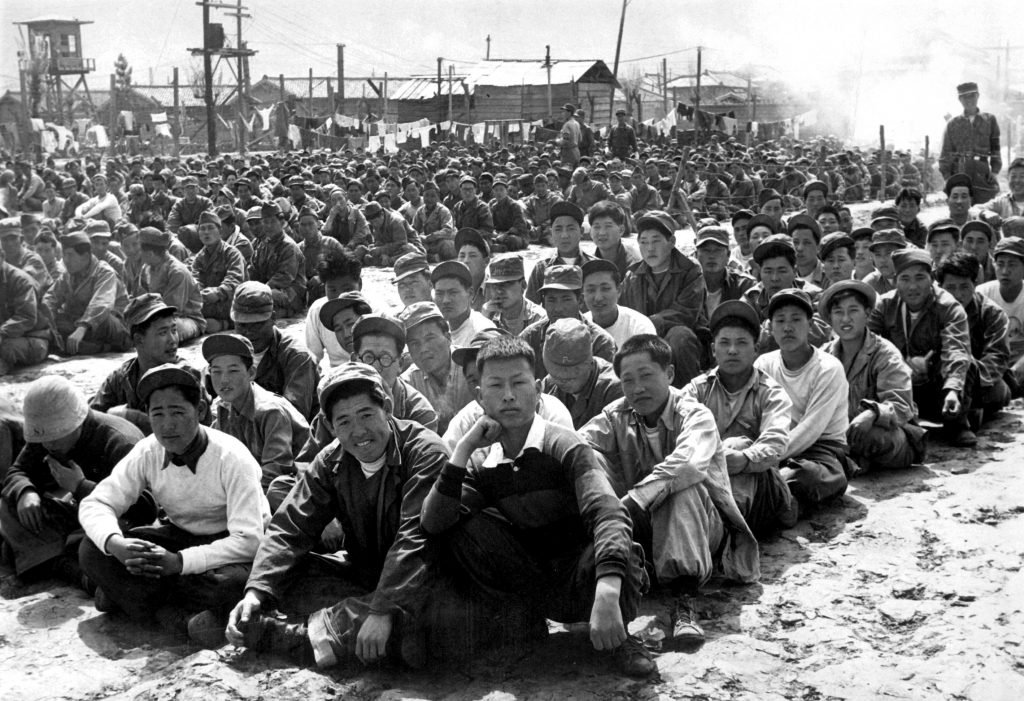

War between nations has caused immense loss of lives, property, economic hardships and psychological trauma for millions over the years. One of the major victims of wars have been the fighters caught by the enemy countries and imprisoned in enemy land. These people are formally referred to as Prisoners of War. Seeing the immense brutalities of war, the Hague Peace Conference laid down certain laws of war in 1899 in an attempt to make war more humane. It adopted conventions relating to customs of war on land and sea. It addressed the issue of prisoners of war as an annexure[1] and provided them with some protections like ensuring humane treatment and the responsibility of the government under whom they are prisoners to maintain them, among others. These were widened to an extent by the Hague Convention of 1907.[2] However, as the First World War broke out and both sides gained prisoners of war, they were treated extremely poorly with many dying out of starvation, unhygienic conditions, excessive labor etc.[3]

Hence, the inadequacy of the current laws of war became apparent vis-à-vis the Prisoners of War and the world came together once more to draft more comprehensive laws. This was what led to the Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of 1929[4]. It expanded on the previous convention however this too proved insufficient with the outbreak of the Second World war and nations committing serious breaches of the Convention using loopholes, for example vis-à-vis the definition of a prisoner of war being only limited to armed forces. Hence the Geneva Convention III of 1949 was drafted by the International Committee of the Red Cross with most of the countries ratifying the convention.[5]

The 1949 Convention replaced the 1929 one. It was more detailed and made an attempt to correct for the limitations of the previous convention. For example, the definition of Prisoners of War[6] was expanded to include members of the armed forces, volunteer militia and civilians accompanying armed forces in order to ensure that maximum people are protected under the law. The Convention has also laid down its applicability in situations of not just outright war but any armed conflict which may arise between two or more countries, even if the state of war is not recognized by them.[7]

Some other important provisions of the Convention include

- Humane treatment of Prisoners of War (POW) with any unlawful act or omission by Detaining Power causing death or injury to the prisoner prohibited. A violation of this particular provision is treated as a serious breach of the Convention.[8]

- Female POWs are to be treated with the regard due to their sex.[9]

- POWs are allowed to correspond with their family members and receive relief packages.[10]

- Seriously ill or wounded POWs must be repatriated or treated immediately.[11]

- As soon as hostilities end, POWs are to be released and sent home without delay.[12]

- The kind of work the POWs can do during their imprisonment has been detailed carefully with caveats about their sanitary conditions and safety requirements as well.[13]

Hence, it is clear that the convention has made immense effort to ensure that the Prisoners of War are protected in the enemy country and are able to return safely as soon as hostilities end. The Convention has received almost universal ratification, including all UN member states. Thus, it has become more of customary international law, binding all nations to its provisions.

India had ratified the Convention in 1950, becoming the fifth country to do so. While we have remained a largely peaceful nation, disputes about Kashmir and boundaries with our neighbors have embroiled us in a few international conflicts, mainly with Pakistan and China. One of the major wars India fought was in 1971 with Pakistan which eventually led to the creation of Bangladesh. After the war ended, the countries met in Shimla to discuss issues of prisoners of war and initiation of peace talks. The two sides agreed to release all POWs with immediate effect. India, following the agreement released all of the over 90,000 prisoners that had been captured. Pakistan too released the prisoners. However, it was eventually revealed that around 54 prisoners of the Indian army and air force mostly were missing. Pakistan claimed it had released all the prisoners it had, and so the missing prisoners ought to have been dead. However, the Indian government has sent two delegations to Pakistan on a fact-finding mission to gather more details of the missing prisoners and it is suspected, based on a few reports by prison inmates and guards, that the prisoners were in fact alive and incarcerated in Pakistan prisons during the time of the war. Their inability to return back home however is a cause for major concern. The Indian government seems to have given up on any information on them, the last delegation having been sent in 2017 and no further apparent action having been taken since then. Pakistan would be in a serious breach of the Geneva Convention if indeed certain prisoners were prevented from returning or subjected to such conditions that they couldn’t survive. A further investigation or approaching the International Court of Justice might help the families of the prisoners find some solace.

Captain G R Choudhary was an Indian prisoner of war who was captured by Pakistan in the same 1971 war. He was one of the lucky ones who survived and returned back home. He detailed some of the horrors he had to endure as a POW in Pakistan in a talk. One particular instance he recounted was of a Pakistani doctor who had to operate on his wounds. He held the scalpel on his throat and asked him why he shouldn’t just kill him right then. The captain had many more such chilling stories which call into question the implementation of the Geneva Convention which expressly forbids such treatment by the Detaining Power.

However, in the recent conflict with Pakistan in 2019, an Indian Air Force pilot, Abhinandan Varthaman was captured in Pakistan was released after 60 hours and was not made to endure any form of torture or violation of the Convention as far as is known to the public. This was a heartening development in the International Humanitarian law field and hopefully will be the precedent followed not just by India and Pakistan but by all the countries of the world.

References

- Shaw M, International Law (9th edn, Cambridge University Press)

- Convention with respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land 1899

- Convention respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land 1907

- Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, 1929

- Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, 1949

- Michael N. Schmitt & Leslie C. Green, “Enforcing The Third Geneva Convention On The Humanitarian Treatment Of Prisoners Of War” (1997), United States Air Force Academy Journal of Legal Studies https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1475&context=ils

- Jones H, ‘British Library’ (Bl.uk, 2014) https://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/prisoners-of-war

- Albert M, ‘Hague Convention | International Treaties [1899, 1907]’ (Encyclopedia Britannica) https://www.britannica.com/event/Hague-Conventions

- ‘Prisoners Of War And Detainees Protected Under International Humanitarian Law – ICRC’ (Icrc.org, 2010) https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/war-and-law/protected-persons/prisoners-war/overview-detainees-protected-persons.htm

- Jeannesson S, ‘International Hague Conferences Of 1899 And 1907’ (Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’Europe) https://ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/europe-europeans-and-world/europe-and-legal-regulation-international-relations/international-hague-conferences-1899-and-1907

- Bouchet-Saulnier F, Brav L, and Michel C, The Practical Guide To Humanitarian Law (Rowman & Littlefield 2014)

- Moorchung D, ‘Indian Prisoners Of War In Pakistan: Bring Back Our Soldiers’ (Deccan Herald, 2021) https://www.deccanherald.com/opinion/main-article/indian-prisoners-of-war-in-pakistan-bring-back-our-soldiers-988608.html

- S. Banerjee S, ‘The True Story Of India’s Decision To Release 93,000 Pakistani Pows After 1971 War’ (The Wire, 2020) https://thewire.in/history/the-untold-story-behind-indira-gandhis-decision-to-release-93000-pakistani-pows-after-the-bangladesh-war

- Sehgal M, ‘1971 Prisoners Of War: Why 54 Indian Soldiers Are Still Languishing In Pak Jails’ (India Today, 2019) https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/1971-prisoners-of-war-why-54-indian-soldiers-are-still-languishing-in-pak-jails-1471928-2019-03-06

- Borkar S, and Kewalramani L, ‘Geneva Convention (Prisoner Of War Status) And Its Applicability In The Case Of IAF Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman – Government, Public Sector – India’ (Mondaq.com, 2019) https://www.mondaq.com/india/terrorism-homeland-security-defence/786258/geneva-convention-prisoner-of-war-status-and-its-applicability-in-the-case-of-iaf-wing-commander-abhinandan-varthaman

- Hegde R, ‘The Missing 56: 1971 War’S Indian Pows In Pakistan Who Never Returned’ (Swarajyamag, 2018) <https://swarajyamag.com/politics/the-missing-56-1971-wars-indian-pows-in-pakistan-who-never-returned> accessed 20 November 2021

- Saluja P, ‘A Case For Abhinandan Varthaman: The Geneva Conventions On Treatment And Release Of Prisoners’ (Bar and Bench – Indian Legal news, 2019) https://www.barandbench.com/news/abhinandan-varthaman-geneva-conventions-treatment-release-prisoner

My Time As A Pow In Pakistan-A Story Of Courage, Pain, Pride And Hope (TedX 2017) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yZd-tCw5_GI

[1] Convention with respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land 1899.

[2] Convention respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land 1907.

[3] Heather Jones, ‘British Library’ (Bl.uk, 2014) <https://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/prisoners-of-war> accessed 19 November 2021.

[4] Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War 1929.

[5] Geneva Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War 1949.

[6] Geneva Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War 1949, Art 4.

[7] Geneva Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War 1949, Art 2.

[8] Geneva Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War 1949, Art 13.

[9] Geneva Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War 1949, Art 23.

[10] Geneva Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War 1949, Art 70.

[11] Geneva Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War 1949, Art 30.

[12] Geneva Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War 1949, Art 118.

[13] Geneva Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War 1949, Section III.