Stuck between giants

India’s neighbourhood-first approach to maintain and enhance its clout in the subcontinent had predominantly followed the ‘elder brother diplomacy’. Nepal is one of its many neighbours that have looked up to India for security as well as a developmental aid. India has been sincere in its assistance across the board – in the development of infrastructure, trade and commerce, investments, transportation, energy, human resource development and defence. In return, however, India’s interference in Nepal’s internal politics had been a small price to pay for Nepal till the first decade of the current century. The unilateral embargos imposed on the land-locked neighbour in 1989 and again in 2015, severely hampered the economy of the country which relied heavily on its “big brother”.

Times however have changed today. Located between two Asian giants, the developed world has begun to recognize the strategic significance of the humble Himalayan nation. Unlike the early 2000s, India is not the only source of foreign investment anymore. The diversification of its foreign assistance is evident from the fact that Singapore, Ireland, Australia and Japan are among 39 other countries that have stakes in Nepal’s FDI. Multilateral banks like the World Bank have become major lenders. While several countries are trying to make inroads in Nepal, the most significant growth has been seen in China’s efforts as part of its progressively increasing footprint in South Asia.

China has been swift to seize the opportunity and space vacated by India during 2015 in an earthquake ravaged Nepal. As a result Nepal became one of the first countries to join the Chinese Premier’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Shifting Parameters

Despite India being the largest trading partner, China is the largest source of FDI for Nepal. China has topped in FDI pledges to Nepal in FY 2015-16, 2016-17 and 2017-18 with growing investment pledges in hydropower, cement, herbal medicines and tourism (Source: Mofa Nepal). FDI from India to Nepal declined by around 81% in the first nine months of 2021 in comparison to the same period in the last fiscal year, meanwhile investments from China have slightly increased and constituted 70% of total FDI received by Nepal in that period (source: Kathmandu post).

Nepal depends on Indian power export to meet its energy requirements considering its vast hydropower potential is untapped. Three cross border power transmission lines have been laid down as funded by the Indian government. Given that India is currently supplying 600 MW of power to Nepal, the unilateral embargo significantly starved the power and energy requirement of Nepalese households. Under such pressing circumstances, Nepal’s shift towards China seems rational. The Chinese under BRI made appreciable investments in power stations and transmission line projects including the Upper Trishuli hydropower project.

Warning bells rang for India when Nepal and China signed the trade and transit agreement –ending India’s monopoly in providing landlocked Nepal access to the sea. With the signing of the agreement, Nepal got access to seven well equipped Chinese ports for third party trade with effect from February 2020. Interestingly, India took initiative for connecting Raxaul-Kathmandu through railway lines only after Nepal made an agreement with China for the construction of the railway; in fact, India hurried up the construction to check the growing influence of China.

Changing allegiances: At what cost?

China’s expansion in the neighbourhood has been a wake-up call for India’s laid-back big brother diplomacy – with China playing on its deep pockets and military clout. The BRI, under which most investments have been made, is increasingly being called “debt-trap diplomacy” – most of the aids extended to the participating countries (which are low income developing Asian nations) are in the form of concessional loans. Several countries in the neighbourhood including Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Maldives have retracted on high-cost contracts and projects initially taken up by Beijing under BRI. A case in point was the ceding of Hambantota port by Sri Lanka to China and the call for Indian financial support by the Abdullah Solih led Maldivian government to repay huge developmental debts the former Yameen led government had incurred from China.

According to research recently published by the Keil Institute for ‘World Economy’, there are seven countries in the world whose external loan debt to China surpassed 25%of their GDP. The study titled “How China lends” analysed 100 contracts between the Chinese state-owned entities and government borrowers in 24 developing countries. The findings read that the contracts contained unusual confidentiality clauses, barring the revelation of the existence of debt and that the cancellation, acceleration and stabilization clauses allow the creditor to influence the domestic and foreign policy of the debtor. (Source: study). This intrusion in political and economic affairs has caused serious speculations among policymakers in the developing world. Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammad has called China’s BRI “new colonialism” and suspended the 20 billion-dollar East Coast Rail Link project as a blow to the growing ambition of China.

Lack of transparency is another feature of the BRI projects. Recent studies have shown that most of these projects are dollar-denominated, financed which might lead to China requiring co-financing with multilateral institutions weakening its pre-determined terms and conditions. (Source: Study). Working according to west-dominated liberal institutions will hinder the Chinese plan.

With regards to some of the most prominent BRI projects, no consensus seems to have been reached between the two countries. The Trans- Himalayan railway line project (Qinghai-Tibet-Keyrung-Kathmandu) had been hailed as the much-awaited transportation project to end Nepal’s dependence on India for third-country trade and transit. To begin with, Nepal lacked funds to conduct a feasibility test despite 50% funding from China for the same. The pre-feasibility study conducted by China Railway First Survey and Design Institute reported that 98.55% of the railway will pass through tunnels and bridges, given the topography and difficult terrain of the region, with an estimated cost of 3.55 billion Nepali rupees per kilometre. Such costs cannot be incurred by Nepal’s $6 billion economy and would require almost complete reliance on Chinese grants. The pace of negotiations has led the Nepali public to widely declare the project a non-starter.

The long-term dependence on roads funded by the Indian government and ports for third-country transit has led to the development of infrastructure. On the other hand, despite the Chinese government granting access to its ports, it will take Nepal several years and heavy costs to create the requisite infrastructure to reach the ports (even the nearest Chinese port is four times farther away than the nearest Indian port). Moreover, the road and rail projects under Chinese supervision are yet to be materialised. Meanwhile, India has fast-tracked many of its developmental projects in Nepal, which is a step in the right direction.

Mending the roads ahead in the neighbourhood

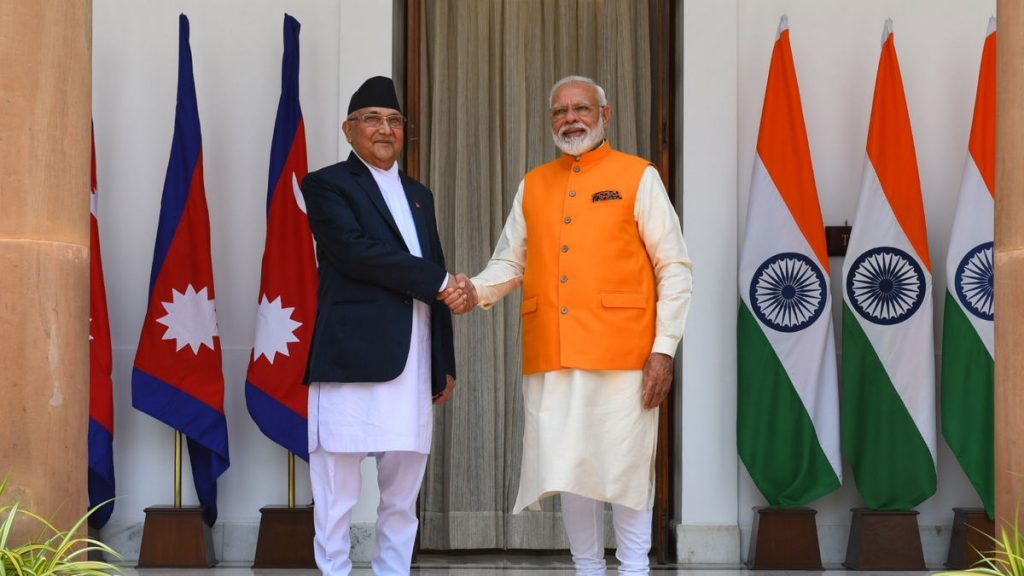

The only way to bring back Nepal in a stable relationship with its former friend is by re-establishing trust which had been eroded by drastic unilateral steps taken by New Delhi without significant consultations with the relevant stakeholders on both sides. Current issues including border disputes and projects stuck in the pipeline need proper government-to-government engagement. The Indo-Nepal joint commission meeting held in January 2021 was especially relevant in this context, soon after which India sent across a million vaccine dosages as grant assistance to generate goodwill. India’s grant in aid to Nepal in 2019-20 was around 1200 crore rupees. Apart from grant assistance, the Government of India has extended lines of credit of USD 1.65 billion for undertaking the development of infrastructure, including post-earthquake reconstruction projects (Source: MEA ).

India has significant advantages in its neighbourhood and despite the growing interference of China, traditional ties can be restored by observing and learning from past mistakes. Currently, both India and Nepal are reeling under severe distress because of the pandemic, not to forget the economic and political upheaval in India and Nepal’s ongoing constitutional crisis. It is important to remember that the two countries are connected by their democratic institutions and the familial and cultural ties of their people – two very strong foundations that China lacks. India must consider resolving disagreements by means of high-level interactions at various bilateral forums between the two countries since a unilateral trade embargo is not only isolating but also tyrannical. This has led several Nepalese scholars to believe that India’s “big brother syndrome” is taking the shape of “hegemonic arrogance” which it can ill afford at the moment. Engaging effectively and addressing the issue of laid back and late delivery of promised projects will go a long way in mending relations with an old friend. India need not confront China aggressively when it comes to its neighbourhood. All it needs to do is go back to being the friend and guide without over-stepping its authority and the allies might drift back, for familiarity is often more comforting especially in times of uncertainty.