China and India: In A New Era of Antagonistic Co-existence

Introduction

As we approach the one-year anniversary of the deadly Galwan Valley clash, Sino-Indian relations have reached a nadir similar to the the 1962 war aftermath. The current state of affairs is being described as one of the difficult phases facing China and India because the glacial process of disengagement combined with increasing militarsation of the LAC has made prospects of further deterioration of bi-lateral ties a high possibility. In other words, the relationship is now functioning within a new framework of antagonistic co-existence or what many experts have termed as armed co-existence. Given, the heightened distrust and threat perception now persisting between the two powers, this phase of antagonistic co-existence is the new normal of Sino-Indian relations where bi-lateral ties are more adversarial, conflict-prone and volatile.

Based on the events and issues that followed the Galwan valley crisis this article seeks to outline and elaborate the major trends emerging in this new phase of Sino-Indian antagonistic co-existence, and what will be their possible impact on Asian geopolitics.

Trends in Antagonistic Co-existence

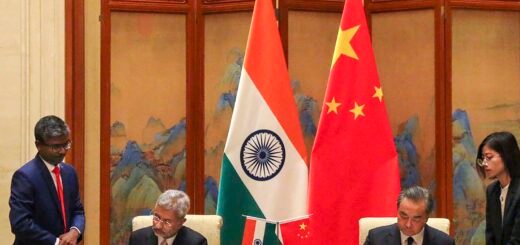

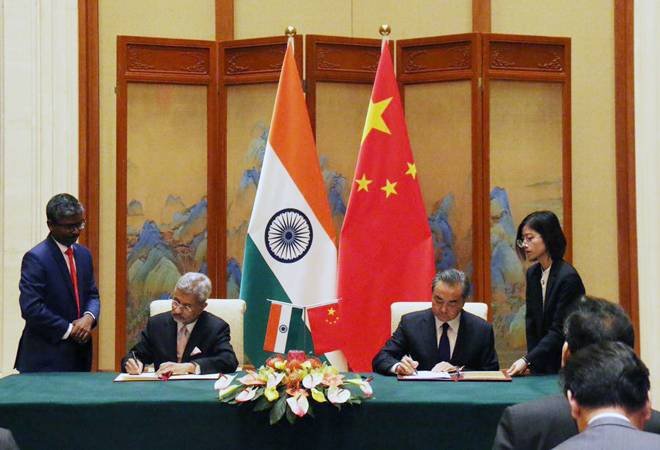

Superficial normalisation of bi-lateral ties is one of the major trends that characterizes Sino-Indian relations in this current phase. Although the two countries have continued diplomatic communication and maintained trade relations (albeit limited),however, in the backdrop of the brutality and violence witnessed during the Galwan Valley clash a superficial normalization has set in whereby, the diplomatic and economic architectures have significantly weakened and are unlikely to generate sufficient political capital to drive bi-lateral ties towards reconciliation. For instance, despite recovering trade figures, the ban on Chinese websites and trade curbs with Chinese companies are in place. Also, while

Indian private companies are procuring critical medical equipment from China, New Delhi has rebuffed Chinese government covid assistance at the state level. Similarly, while China offered diplomatic condolences over India’s covid crisis, however, hiked prices of critical medical supplies, briefly stopped Cargo flights to India and mocked New Delhi’s management of the covid crisis on Chinese social media. A primary reason of this estrangement is the military security dilemma being permeated by partial disengagement between the countries. Moderate expectations of renewed hostility and mutual willingness to use force have significantly constrained co-operation. Also, post-Galwan valley clashes there persists a heightened sense of victimhood in both China and India, whereby a perception of being repeatedly wronged by the other has created political exasperation and also reluctance to initiate actual reconciliatory measures lest it is taken as a sign of weakness by the other.

The second prominent trend in Sino-Indian ties, is high securitisation of the border dispute. This high securitisation followed almost immediately after the clashes, demonstrated by the rapid mobilization of military forces on both sides, symbolic visits by Indian and Chinese leaders to their respective sides of the border and emergence of hostile public rhetoric in both countries. Nearly one year later, the securitization is most evident at the operational level. In December last year New Delhi had authorised the Indian armed forces to stockpile military supplies for fifteen days of intense warfare, an increase from the earlier guideline of 10 days of general warfare with China and Pakistan. This year too amidst the financial stress the Indian Government increased the military budget by three percent with monetary allocation for procurement of new arms increasing by sixteen percent from the previous year and more importantly the Indian Army has instituted key changes in ORBAT (Order of Battle) to respond to PLA military offensives. On the other side of the Himalayas, China similarly in accordance with Premier Xi Jingping’s instructions for battle preparedness has retained large number of troops for emergency mobilization and is conducting frequent military exercises in spots very near to the Indian front in eastern Ladakh. Also, according to media reports, China apart from upgrading its military and civilian infrastructure in Tibet is renovating a missile launch site and has initiated a drive to recruit Tibetans to fight the Indian army. The high securitisation can be attributed to the sudden breakdown of the rules of engagement between the two countries which has led to significant confusion on both sides about the new terms of engagement. In this context, the two countries, given their respective territorial anxieties are viewing the border dispute as an existential threat. Consequently, this will lead tensions to linger where China and India will disengage but might not de-escalate.

The third major notable trend in this phase of antagonistic co-existence is the added emphasis on external balancing, especially in India. New Delhi till now had followed a policy of strategic hedging which was relatively accommodative of Beijing’s concerns and insecurities. However, the Galwan valley incident has raised serious questions regarding the policy effectiveness of placating China and New Delhi’s own internal capability to counter the Chinese offensive. Therefore, in this context when India’s internal capacity to balance China is increasingly falling combined with the low political will to accommodate Beijing, New Delhi is putting added emphasis on external balancing to contain China’s perceived aggression at the border. It is important to note that India’s current balancing strategy has two elements, one at the geo-territorial domain and the other at the maritime domain. With regard to the geo-territorial domain, India has oriented towards re-strengthening its ties with Russia, as an attempt to temper Chinese misadventure at the border. The Indian Foreign Secretary Harsh Shringla’s visit to Moscow in February 2021 followed by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s visit to India in April 2021 sealed the deal on S-400 missiles despite opposition from the United States is indicative of New Delhi’s renewed attempts to boost bilateral relations. Further, in the maritime domain New Delhi is pro-actively pursuing rejuvenation of QUAD as a politico-military alliance and at the first leader-level meeting discussed strategies to counter China’s economic and military power. The idea is to create an alternative pressure point near Malacca, should China pressurise India at the Eastern and Western sectors of the border. Beijing on the other hand till now has not resorted to active counter-balancing against India, however, has taken few steps like maintaining close diplomatic-military ties with Russia, have stepped in to provide vaccines and covid-assistance to India’s neighbours (after the failure of India’s vaccine diplomacy), and is closely monitoring the developments regarding QUAD to the extent of warning India’s smaller neighbours like Bangladesh against joining the informal alliance.

Conclusion: Antagonistic Co-existence and Impact on Asian Geopolitics

Foreign policy scholars and experts in both countries acknowledge that Sino-Indian ties are of immense significance for larger Asian stability and security. Accordingly, major disruption between these two powers is likely to impact the security, economic and governance structures of the Asian region. South Asia might become one of the first victims. While a balanced competition between China and India allows the smaller countries to maintain relative strategic independence by hedging between the two powers, however, deeper hostility and unrestrained competition will be a constant menace for the smaller neighbouring countries who hope to benefit from the economic

development in both China and India. Moreover, since neither India nor China will be able to hegemonize South Asia completely, persisting antagonism between Beijing and New Delhi will impede South Asia’s collective capability to address issues of trade, connectivity, infrastructural development, terrorism among others. Another undesirable consequence of Sino-Indo antagonism will be greater militarisation of the Indo- Pacific. The region has already witnessed significant militarisation owing to Sino-US competition, now New Delhi joining United States’ endeavours to contain China at the maritime domain will add to maritime hotspots of conflict. Subsequently, competing military patrols, acquisition of military bases and deployment of power projection capabilities by the major players in the region will bring in to the sea highly advanced systems of combat that combine both conventional and non-conventional power. Such a development will not only widen the scope of conflict but is particularly dangerous as the region houses four nuclear powers. Former National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon has argued that this phase is a temporary one and shall last for a decade. However, the question remains whether by that time Sino-Indian antagonism will erode the gains painstakingly achieved over the years or both countries will exercise political prudence in favour of long-term interests.