The tale of Amb Temples

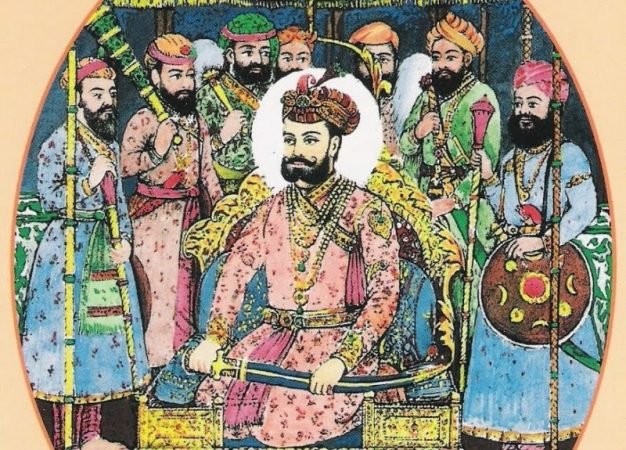

The Hindu Shahis stood at a face off against the Ghaznavids, under Anandpal’s leadership, for one ultimate time, primarily to decide the fate of the nation, the northern boundaries of what they stood guarding for almost two centuries: Hindustan! With Jayapaldeva’s humiliating defeat at the hands of Mahmud in 1001 CE, Anandpal, Jayapal’s son and a favourable successor of the centuries old Hindu Shahis, had come forward to lead a confederacy of the local rajahs and the almost extirpated Kshatriyas, against Mahmud. An intense battle was what kicked off next, on the rugged fertile plains of Chhachh, (“a region located between Peshawar and Islamabad at the northern tip of Attock”), in which Anandpal, the king who was then considered as an invincible descendant of Porus, ended the battle the similar way his probable ancestor had ended one with Alexander, thirteen hundred years ago: a truce! History had to repeat itself and once again, the boundaries of the nation fell short for keeping the invaders at bay. Mahmud returned pompous and his purpose to loot the moneyed kingdoms of Hindustan, was partially accomplished.

Two years later, in 1010 CE, Anandpal, the king upon whose tactics the masses had placed their hopes high, passed away under normal circumstances, and a massive financial and territorial possession of the Hindu Shahis was lost to Ghazni.

Trilochanapala, son of the great king, sat on the gilded throne next but failed miserably to restore the dynastic prestige to its previous stature. Executed by his own soldiers in 1021 CE, he was succeeded by Bhimpala of whom not much is known other than the fact that he was possibly the very last of the once powerful Hindu Shahis. With his death, the empire that once stood guarding the borders of Hindustan like none other, faded away into uncertainty and was absorbed by internal conflicts and foreign invasions that led to the rise of the Saffarids, the Samanids and the Ghaznavids.

Their monumental forts and palaces soon waned into desolation, dying in despondency, and the region, culturally and religiously now, populated with people of the Islamic faith, failed even to recall the once massive temples (Tilla Jogian, Nandana, Katas, Malot, Amb, Kafir Kot and others) dotting the Sakesar Salt range.

In his article for The News on Sunday Pakistan, Omar Mukhtar Khan aptly calls out that, “It takes one around an hour from Quaidabad to reach Amb. The road actually passes through what was once the Amb fort complex, to reach another town down the hill. Such is our ‘love’ of built heritage that we allowed bulldozers in this archaeological site to clear the way for the road. Locals speak of instances of finding coins or clay pots but no systematic record has been maintained.”

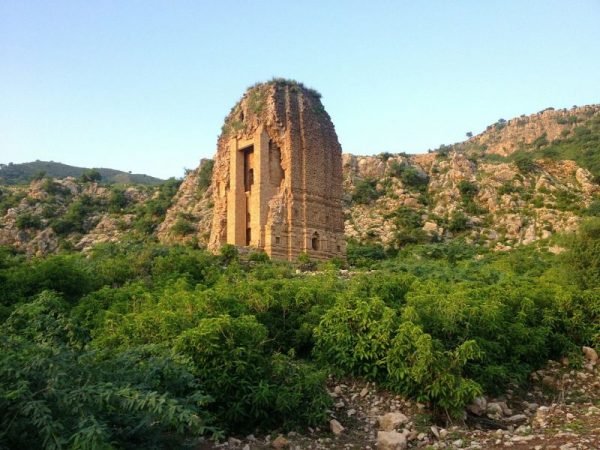

Salman Rashid, in his work entitled, “The Salt Range and the Potohar Plateau” describes in detail, the ruins of the two temples that are considered to constitute the Amb Temple Complex. The main temple is observed to be around “eighteen metres through three storeys”, and is probably “the loftiest of all Hindu Shahya edifices in the Salt Range. It is imposing, too, because of the bulky pillars fronting it and giving it a clear Greco-Roman appearance. Made of the same pale gray limestone, the pillars appear to be part of the original building plan. Closer inspection, however, reveals the jagged remnants of a vaulted foyer that once afforded entry to the main chamber.”

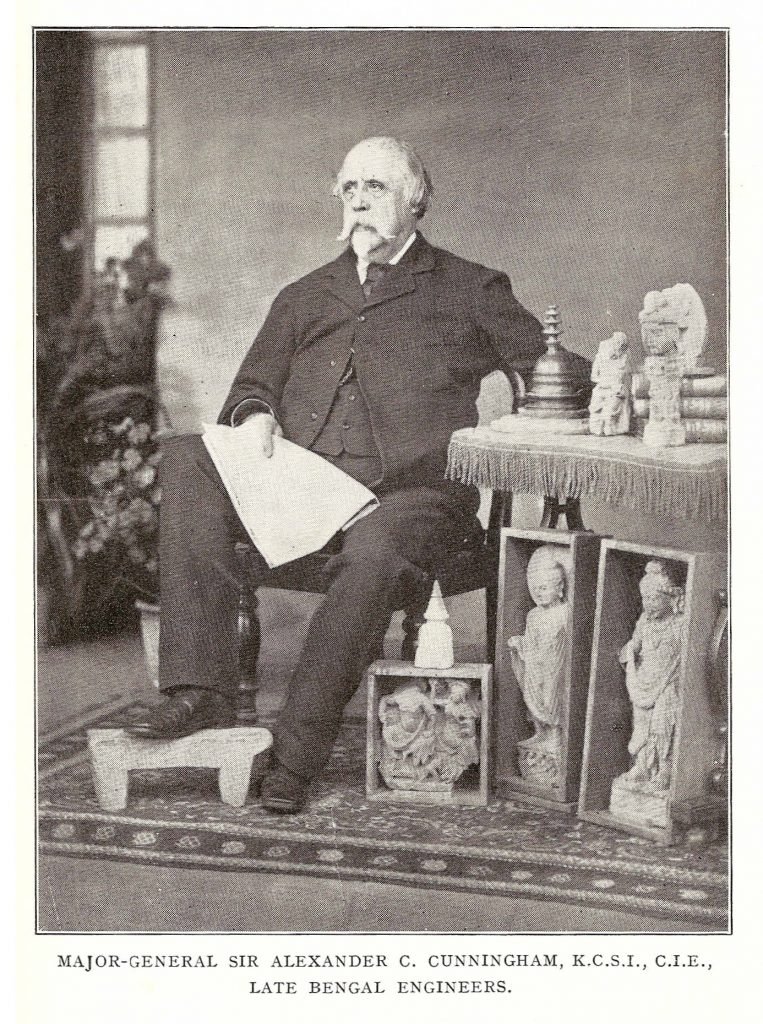

Sadly, there exists no established view till date, with regard to who originally built the temples. Alexander Cunningham is said to have visited the site in the early 1860s and inspected the area for a certain stone tablet (something that probably had an inscription on it) that purportedly went missing and was never recovered!

However, there are two separate views on the origins of the temple complex, one by Cunningham himself, after having been informed of transliterations of the missing stone tablet by a Brahmin, and the other by Orientalist Colonel James Tod, as penned down in his famed work, “Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan”.

Cunningham credits Raja Ambarikha, the son of Mandhatari, a Suryavanshi Rajput with the establishment of both the temple and the city, in around 1st century CE.

Similarly, Colonel James Tod opines that this place was established not by Ambarikha, but by one Ambarisha, fortieth in the line of the glorious Sun Lineage princes.

Taking both the aforementioned views into consideration when writing about the temple and its origins, Salman Rashid, the noted travel writer, dismisses both of them and propounds his own theory of the establishment of the temple.

He quotes, “The truth is that Amb, like the other Hindu Shahya temples of the Salt Range, was built after the annexation of this part of the country by the great Kashmirian conqueror Durlabhaka Pratapaditya in the 7th century AD. Even then, unfortunately for the chronology given on the purported stone slab, one infallible dating element in the building shows that the temples of Amb were not built until about the end of the 10th century. The cinquefoil arch that repeatedly appears in the niches on the facades as well as on the entrance of the smaller temple – as surely as it would have crowned the now obliterated entrance vault of the larger building – is posterior to the trefoil arch seen at Malot. This element, the natural outcome of experimentation with embellishment and elaboration, followed in the course of development of the earlier trefoil arch and marks all later Hindu Shahya buildings in the area.”

Talking about Pratapaditya, the Kashmiri conqueror in whose support Rashid has put his views forward, art historian Michael Meister, in his work entitled “Fig Gardens of Amb-Sharif, Folklore and Archaeology”, published by Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente, observes Kashmiri motifs on the exteriors of the temple architecture, sometimes including a cusped niche, something that affirms what Salman Rashid propounded in his work.

However, going by what W.S. Talbot, ICS, in his paper, “An Ancient Hindu Temple in the Panjab”, published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1903, states, the resources that support the Kashmiri theory, are proved insufficient enough to be considered established! Talbot intricately observes that the architectural get-up of the main temple differs much from what we know as the Kashmiri Style (temple with sloping and pointed rooftop), and is more or less similar to the Kalar and Kafir Kot temples in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province.

As for the temple complex, there were two other temples, smaller in size (around seven to eight meters in height), located some seventy five metres away from the primary structure, atop a cliff with a vestibule chamber overlooking the main temple complex. One of these smaller temples survive till date whereas there’s almost no visible sign of the other having ever existed. Furthermore, the temples, having been built up on an elevated hillock, could have possibly provided for military support too, evident from the now demolished fortifications around the temple ramparts, the earliest of which, date back to the Kushan period.

In his column for the News on Sunday Pakistan, Omar Mukhtar Khan also details on the surrounding areas of the temple courtyard that include but are not limited to, the lush green mountains, the Ucchali lake which serves to be a breeding ground for birds coming from afar, the fortifications around the area known to the locals as ‘Rani wala mehal’ and of course, an abandoned Dak Bungalow near Dhoda Nallah.

However, through the centuries that passed since the complexes being abandoned, the Amb Temples have often been looted as a result of which mysterious cavities or vacant spaces, along its walls, are found today. Although the temple site is protected under the Pakistan Antiquities Act (1975) and any harm, however slightest it might be, to the temple complex is an offence in the eyes of law, it would be apt enough to conclusively quote what Omar opinionates, having visited this place of excellent historical and cultural significance, himself.

“I saw people climbing up to the roof of the main temple to take photographs, essentially risking both their lives and damaging the already crumbling monument…The whole complex is surrounded by a moat and walls which makes it probable that it was established as a fort. However, unless properly preserved, these remnants would be soon gone…Amb temples are part of our ancient heritage and both people and the government have a responsibility towards preserving this gem in the middle of lush green rolling mountains. The site should be protected and an archaeological research project as well as tourism promotion undertaken.”