The borderline difference between India and China post-1962

1962 enabled China to establish an international identity ideologically and politically distinct from that of the Soviet Union. Its military victory and its unilateral withdrawal enhanced its image and standing in the third world. It paved the way for China to play an independent role in world affairs. By contrast, for India, the year proved a trauma. The collapse of the India-China amity effectively destroyed the structure of Nehru’s foreign policy. It did more: it shook the foundation of his worldview. After 1962 the two concerns became most pressing for it. The one was territorial definition and consolidation which became the core problem in its relationship with all neighbours, especially China and Pakistan. The other was an active search for security vis-à-vis China. In the aftermath of the war Nehru, perhaps as his last brave act, attempted to moderate the mood of the Parliament and advised it not to shut the door to the possibility of future talks with China, and not to cast China as an ‘enemy’. It, however, was a definite end to a more expectant past and a new beginning for India and China in almost every aspect of state life.

Initiation of border problem

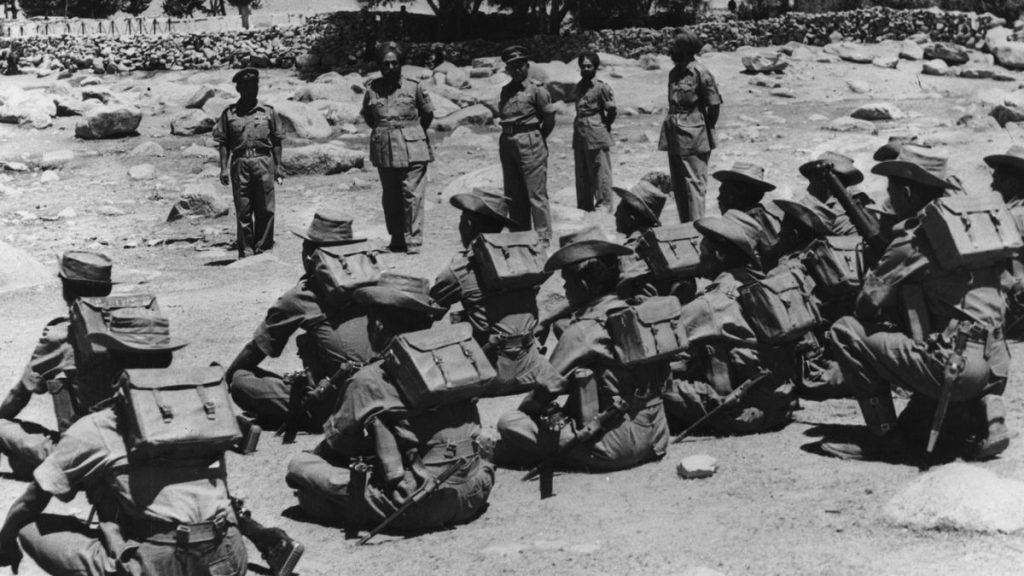

The borderline difference between India and China despite being in existence took an alarming proportion with the developments in Tibet at the close of the 1950s and it resulted in a declared war in October 1962 with India’s humiliating defeat, which sealed the fate of India-China relations in all spheres for the long fourteen years. In 1962 while China was ready for massive aggression on India, the later think the disaster either physically or mentally and no one who lived in India through the winter months of the year can forget the deep humiliation felt by all Indians, irrespective of party. However, even after the border conflict New Delhi did not close its option of a negotiated settlement of all outstanding problems and sought a realistic co-existence with Beijing, yet the adverse relationship between the two by and large, operated at a stabilised level and sometimes became more intense on account of open Chinese support to Pakistan in its 1965 and 1971 war with India. It was only from the mid-1970s that both sides began to feel the need for mutual cooperation and keeping in view the aspirations, they responded positively which suggested the winds of change in their relations. In line India-China talks on the border, the problem began in December 1981 and passed on from normal border talk to Joint Working Group (JWG) to the meeting of Special Representatives. Till today, in all along the period above 40 round of talks have been conducted but the problem is nowhere near in its solution. Although over the years, India’s relations with the People’s Republic of China have, no doubt, improved largely in the economic sphere, in particular, the continuation of the vexed border problem between them tells us sufficiently about their mutual deficit of trust and sympathy in each other’s perception and pursuit.

Background of border talks

The unresolved border issue, a legacy of the India-China war of October 1962 cast a long and deep dark shadow on areas of engagement in the post-war period. Although ambassadorial level relations between them was restored in April 1976 the first positive development on the part of China came when greeting the Indian diplomat in 1970 said that India is a great country and that India and China should be friends again. The border issue between them was intensified after administering a blistering defeat in the 1962 war, the Chinese forces withdrew 20 Kilometers behind the Mc Mahon Line, which China called “the 1959 line of actual control” in the eastern sector and 20 Kilometers behind the line of its latest position in Ladakh, which was further identified with the “1959 line of actual control in the western sector. This left China in possession of 23,200 square kilometres of territory in Ladakh. India asked for status quo-ex-ante as of September 8, 1962, in all sectors, which China rejected. It resulted in a stalemate on the boundary dispute. The Indian suggestion of status quo was further refuted in December 1964 by Chou Enlai while speaking to the National People’s Congress in Beijing he called the suggestion of restoration of the status quo as of September 8, 1962 “an unreasonable Indian pre-condition”. He declared on the occasion that China would never dismantle its posts and reminded India that China had not relinquished its claim to an additional 90,000 square kilometre south of the Mc Mahon Line. This territorial demand was in addition to the 23,200 square kilometre in Ladakh that was already with China. Thus, the bigger border issue, if made central to the further development of Sino-Indian relations, would effectively freeze any progress towards entente.

Further developments

In fact, the conflict left a trail of bitterness whose traces are still present in their relations. For many years to come their mutual hostility determined their foreign policy. There were no ambassadors in each other’s capital for many years and there was a virtual absence of contact. There is nothing worse for a country’s image than defeat, as the prestige and image of a nation get tarnished. Its capacity to influence other nations gets seriously affected. As J. F. Kennedy aptly put it: ‘Victory has many fathers, defeat is an orphan’. Internationally, they traded abuses and generally adopted opposite standpoints. Peking was engaged in a full-scale campaign against India, a chief purpose of which was to carry the conviction that India was no longer non-aligned but was firmly in the American camp. With Chinese propaganda and its alliances against India, now the later was deeply suspicious about Chinese motives and designs. India believed that China wanted to dominate Asia as Lal Bahadur Shastri, the then Prime Minister of India, said in Parliament, ‘To justify its aggressive attitude, China is pretending to be a guardian of Asian countries, who, according to China are being bullied by India. The basic objective of China is to claim for itself a position of dominance in Asia, which no self-respecting nation in Asia is prepared to recognise’. The annual report of the Ministry of External Affairs for the year 1964-65 spelt-out India’s perception of Chinese motivations. After a long period of hostility and strife from the mid-1970s, the two countries felt the need to normalise their relations and accordingly they moved in this direction, although slowly. In line, China participated in the 33rd Table Tennis Championship at Calcutta in February 1975. Peking began to respond to the earlier Indian initiatives.

The relations between India and China were stepping further and the two were talking quietly about the normalisation of relations which was culminated in the sudden announcement of restoring diplomatic relations. Y. B. Chavan, the Foreign Minister of India, declared in the Lok Sabha on 15 April 1975 that New Delhi has decided to sent an ambassador to China and designated K. R. Narayanan for the post. Earlier the Chinese had taken the view that since India had recalled its ambassador first, she should take the initiative in sending one back. Following India’s announcement, Peking declared its decision to appoint an ambassador in New Delhi. Relations improved gradually since 1976 when diplomatic relations were restored at the ambassadorial level. This exchange of ambassadors did not by itself signify a detente but it had come to represent an important political step for a return to normalisation. Since then, the cultural exchanges between the two countries were also on rise.