Chinese Strategy in the South China Sea

By now, it is clear that China has decided to ditch Deng Xiaoping’s foreign policy dictum of “hiding its capabilities and biding its time” in favour of a much more active foreign policy. Under President Xi Jinping, China has seemingly formulated a grand foreign policy, it is much more aggressive in its approach and seems to be following different diplomacy where, on one hand, Chinese government agrees to cooperate and resolve disputes through negotiation and cooperation of all the parties while on the other it continues to carry on its seemingly unlawful activities on the ground. This is clearly visible in the case of the South China Sea dispute.

Along with all the other issues demanding China’s attention in 2020 – the virus, its trade war with the US, Hong Kong’s national security law, and a host of economic woes – the South China Sea was also revived as an arena for serious tensions. It is befitting to say that no international maritime dispute has garnered more attention than the contest over the islands, reefs and waters of the South China Sea. The dispute involves the overlapping claims of six governments (Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Vietnam and China) to territorial sovereignty and maritime rights, encompasses the main sea lines of communication that connect Southeast Asia with Northeast Asia, covers large fishing grounds and may contain vast reserves of oil and natural gas.

Given the strategic location of the sea, the number of vast resources and the fact that 30% of the world’s trade ships pass through it to the booming economic market of east Asia, it feels fair to say that in the geopolitical games of South China Sea the stakes are high for all the claimants. And high stakes attract the bigger players and so, the US enters the equation. Currently, the USA is the only superpower in the world but it is challenged by none other than China. However, China can’t possibly take over the US just yet but right now it is important for the USA to remain relevant as a net security provider in the region in order to maintain and somewhat justify its position as a world leader and hence we see replacement, followed by the wide acceptance of the terms like “Indo- Pacific” instead of “Asia- Pacific” and the return of a stronger “Quad”.

Consolidating Claims

Seems like China has been “carrying the burden” of its past in the most conducive way possible, in the sense that the contemporary basis for China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea is a statement that Chinese premier Zhou Enlai issued in August 1951 during the Allied peace treaty negotiations with Japan. In the statement, Zhou declared China’s sovereignty over the Paracel and Spratly Islands. Since then, China has been persistently reaffirming her claims through various declarations and government statements. The claim is usually phrased as: “China has indisputable sovereignty over the Spratly Islands (or South China Sea islands) and adjacent waters.”

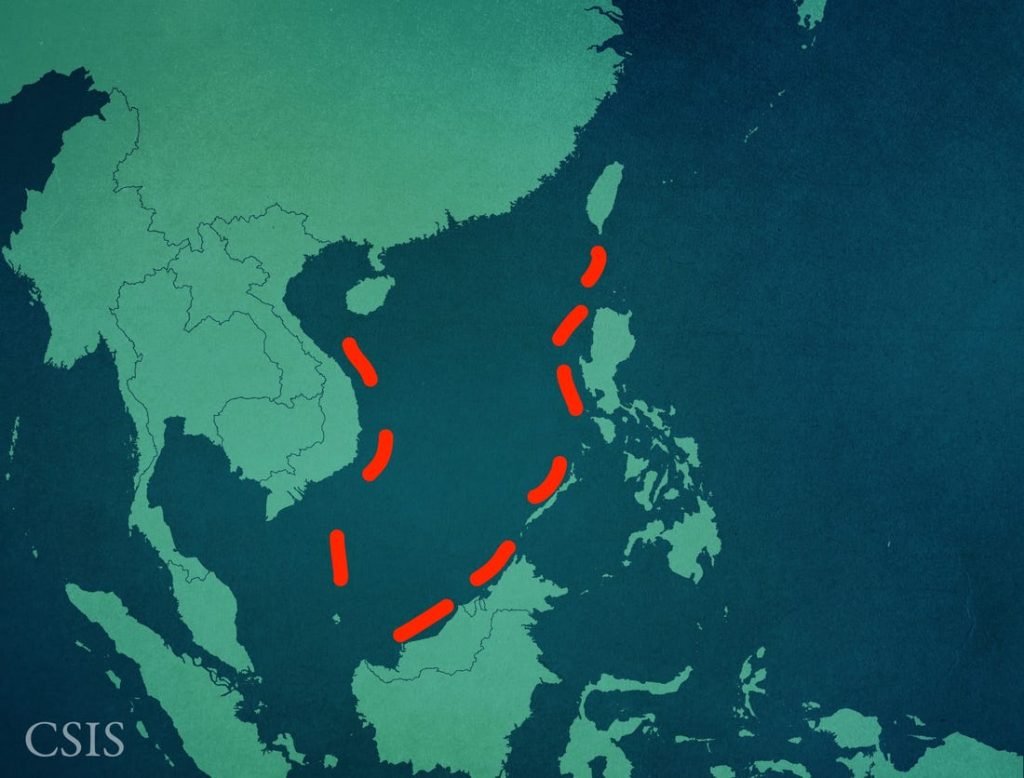

However, with time, as the international maritime legal regime evolved, China began to codify its claims to maritime rights through the passage of domestic legislation. These laws harmonized China’s legal system with the requirements of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and today, China stakes claim to most of the South China Sea and at the heart of this claim is the U-shaped ‘nine-dash line’ that includes as much as 90 per cent of these waters.

Now, what is this Nine dash line? The “nine-dashed line” or jiuduanxian appears on official Chinese maps of the contested region. The line was initially drawn in the 1930s, and it first appeared on an official Republic of China (ROC) map in 1947 and has appeared on the People’s Republic of China’s maps since 1949. Neither the ROC nor the PRC has ever defined what type of international legal claim the line depicted. To this day, the line remains undefined. But, if China’s official statements and laws are taken at face value, then only one interpretation of the line may be possible: it depicts China’s ‘indisputable sovereignty’ over the South China Sea.

The Delaying Strategy dynamics

However, amid all this what’s deeply intriguing to me as an International Relations student is China’s South China Sea Strategy. How does China plan to stand firm against all the other claimants, the regional players and the world power? Well, when carefully examined, one can understand that Since the mid-1990s, China has pursued a strategy of delaying the resolution of the dispute, and what possible purpose could this serve?

Evidently, the goal of this strategy is to consolidate China’s claims, especially to maritime rights or jurisdiction over these waters, and to deter other states from strengthening their own claims at China’s expense, including resource development projects that exclude China. Since the mid-2000s, the pace of China’s efforts to consolidate its claim and deter others has increased through diplomatic, administrative and military means. Although China’s strategy seeks to consolidate its own claims, it threatens weaker states in the dispute and is inherently destabilizing. As a result, the delaying strategy includes efforts to prevent the escalation of tensions among the claimants.

By choosing delay as a strategy, China has opted not to pursue a strategy of escalation of seizing disputed features from other states or compelling them to abandon their own claims to maritime rights. Instead, the strategy seeks to consolidate China’s ability to exercise jurisdiction over the waters that it claims. Because the strategy seeks to consolidate China’s claims, it weakens the position of other states and is destabilizing. Consistent with the logic of the security dilemma, actions by one state to consolidate its claim will be viewed as threatening by the other claimants, especially when such actions are undertaken by the strongest state in the dispute. Take, for example, the case of artificial islands. In 2015, China was reported to be building artificial islands in the South China Sea which aimed to play two roles, increase China’s EEZ in the South China Sea and acting as the military bases in the region. It can also be predicted that China is trying to create settlements on these artificial islands. Once people of Chinese descent start living there, it will make China’s claims for those islands stronger and seem more legitimate.

For the longer run, to make its delaying strategy lucrative China has used the diplomatic instrument of statecraft at several occasions.

First, China maintains that it is open to negotiations. Chinese leaders have continuously repeated foreign minister Qian Qichen’s 1995 statement that “all disputes should be resolved by peaceful means on the basis of the provisions of the international law, including the 1982 UN Convention of the Law of the Sea.” Nevertheless, China calls for bilateral talks with each claimant, not multilateral ones. This position supports the delaying strategy because China knows that other claimants are reluctant to accept these terms. China can indicate a willingness to negotiate without actually having to talk and instead defer resolution of the dispute to buy time to consolidate its claims.

Second, as a routine matter, China responds to the sovereignty and maritime rights claims of other states. International law demands that states actively maintain their claims, especially when challenged by other states. Typically, China responds through a statement issued by the Foreign Ministry.

Third, China has used diplomacy to prevent commercial activity in disputed waters. In the mid-2000s, Vietnam increased its efforts to develop its offshore petroleum industry in cooperation with foreign oil companies. In response, China issued eighteen diplomatic objections to foreign oil companies involved in exploration and development projects between 2006 and 2007. By objecting to these projects, China sought to defend its maritime rights in the face of a perceived challenge and to deter foreign oil companies from engaging in exploration and development activities with other claimants.

The most noteworthy element of China’s delaying strategy has been a greatly enhanced effort to exercise jurisdiction over the waters that it claims through the activities of civil maritime law enforcement agencies. Such efforts have often occurred in response to the commercial activity of actors from other claimant states, especially in the area of fishing and hydrocarbon exploration and development.

Moving on to another important component. The military instrument of statecraft has played a secondary and indirect role in China’s delaying strategy in the South China Sea. For the most part of its history, China has been a land power but for the most part of its history, China didn’t aspire to be a Superpower. That situation has visibly changed and lately, China has used displays of its modernizing naval capabilities in patrols and training exercises to bolster its ability to defend its claims and to deter others from challenging China.

China’s commitment to its claims in the South China Sea is longstanding and unlikely to change. A delaying strategy that seeks to consolidate China’s claims and deter other states from strengthening their own claims only raises further obstacles to future compromise. Although compromise over contested sovereignty or maritime rights is possible, it is highly unlikely under current conditions. China’s emphasis on consolidation and deterrence seeks to maintain the status quo in terms of the control of contested features while strengthening China’s ability to exercise jurisdiction over the waters it claims. Nevertheless, although China’s strategy seeks to consolidate its own claims, often responding to the moves by other claimants, it threatens weaker states in the dispute and is destabilizing if unchecked or not moderated.

China is riding high on its rise. Its speedy and steady economic, military and technological developments along with Xi Jinping’s assertive foreign policy and diplomacy put it on the high table and it is impossible to ignore now. China is no longer Deng Xiaoping’s China. It is more resilient now than ever and to balance China, let alone counter it, requires proper execution of a carefully articulated geopolitical strategy. The revival of Quad can be seen as a small fraction of such a strategy that will test China’s patience in the South China Sea and the larger geopolitical game of the Indo- Pacific region.