The Reorganisation of Jammu and Kashmir and the First DDCs Elections

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown, several administrative changes have permeated Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) since the de facto abrogation of article 370 (and 35 A). These changes under the Reorganisation Act, 2019, apparently put an absolute closure to all political negotiations between the Union Government of India and the secessionist leadership of J&K. The Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP)-led Union Government of India firmly calls the current administrative changes better than any previously held negotiations and experiments and uttered that these are necessary steps to integrate J&K with “mainstream” India. The Home Minister affirms that “all development is going on” and rebuffs any claims of violence and people’s dissonance vis-à-vis the government’s decision of scrapping J&K’s special status. He sturdily pronounced that the new structure would establish a grass root-level democracy, retract youths from militancy and enable the newly formed Union Territory of J&K to function like other parts of India.

Contrary to the BJP’s assertions of development and denial of violence stands the People’s Alliance for Gupkar Declaration (PAGD), a political alliance formed on the principles of the Gupkar Declaration II (signed on 22 August 2020). It is an alliance of mainstream political parties in J&K politics, including the National Conference (NC), the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), the Communist Party of India-M (CPI-M), Jammu and Kashmir People’s Conference (JKPC), and the Awami National Conference. Farooq Abdullah, the patriarch of the NC is the president of PAGD. He is regarded as the pioneer of the alliance as both the Gupkar Declarations were signed at his residence situated in the Gupkar Road. The objective of the alliance is to politically pursue the Union Government to restore the special status and statehood of J&K. The alliance is objecting to the changes that are “hurriedly” occurring in J&K under the J&K Reorganisation Act, 2019 and criticized the BJP for blatantly executing the betrayal and breaking the promise India had once made to the people of J&K when they chose to accede to India under special arrangements mentioned in the Treaty of Accession.

Since the formation of the PAGD, the BJP leaders consistently mocked it as a “Gupkar Gang”, “hungry for power” and only “deceiving” the people of J&K. The BJP leaders vehemently accused them of creating a false narrative of people’s dissonance and only jeopardizing the future of Kashmiris. The name of the PAGD’s stalwart Farooq Abdullah in the released list of the beneficiaries of the J&K State Land Act also known as the Roshni Act, 2001 that had vested the ownership to occupants has intensified BJP’s attack on the credibility of the alliance. The PAGD in response accused the BJP of using state machinery to malign their leaders who are representing J&K’s resistance against ‘BJP’s agenda of diluting its autonomy and identity’. Leaders of PAGD, such as Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti had also accused the authorities as they had alleged that some PAGD candidates were held against their will in some areas during election campaigns and were prohibited to campaign for the DDCs elections. These allegations, however, were dismissed by the Election Commission.

Apart from BJP versus PAGD, the Indian National Congress (INC) has also called the bifurcation “arbitrary and unjust”. Despite INC’s agitation to the changes in J&K, it has distanced itself from the PAGD and has only provided external support to the alliance in its determination to counter BJP and its associates in J&K politics. Meanwhile, the restrictions on foreign correspondents of international media houses to travel to Kashmir are abstemiously lifted. Some of them, including the New York Times and the Financial Times, were permitted to survey the maiden DDCs elections and interact with politicians and citizens.

The Reorganisation of J&K

For many observers especially critics, the process of the Reorganisation of Jammu and Kashmir is moving at an unusual pace. For instance, M.K Narayana, the former National Security Advisor of India considering the scenario has advised the J&K policymakers to not avoid the significance of previous negotiations and accords that have shaped the relationship between India and J&K since 1947.

Last year, on 31 October 2019, the erstwhile special state officially bifurcated into two union territories: 1) J&K and 2) Ladakh, constituting Kargil and Leh districts. The bifurcation was implemented after three months of bureaucratic manoeuvring that has brought significant structural changes in the erstwhile state. As per the directive, the Union Territory of J&K would constitute – an elected legislative body, a chief minister, and a lieutenant governor. Whereas, Ladakh would have two hill development councils and a lieutenant governor. In the Lok Sabha (House of the People), J&K and Ladakh are allocated 5 seats and 1 seat respectively. In the legislative assembly, the J&K would have 107 seats (including 24 vacant seats of the Pakistan Occupied Kashmir). In these 107 seats, some seats would be reserved for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes as per their proportion in the population. The J&K Reorganisation Act 2019 (passed on 9 August 2019) has empowered the Union Government to repeal and modify several state laws from both the Union Territories. Some crucial state laws such as the Ranbir Penal Code and the Wakafs Act (2001) are repealed and replaced by the Indian Penal Code and the Central Wakafs Act respectively. The land laws that had limited ownership rights in J&K were also repealed.

In early 2020, the government has introduced the New Domicile Policy that had replaced the law on Permanent Resident (PR) status. The New Domicile Policy has paved the way for three excluded communities (the Scheduled Caste Valmiki Community, refugees from West Pakistan; and Gorkhas) that remained marginalized despite their years of residency in J&K to acquire domicile certificates of J&K. Additionally, the Union cabinet passed an order that has further modified the applicability of domicile conditions to all levels of occupations in the Union territory of J&K under the J&K Civil Services (Decentralisation and Recruitment) Act. The New Domicile Policy defines anyone who has resided J&K for a period of 15 years, studied in J&K for at least seven years, and appeared in High School and Intermediate examinations located in J&K or registered as Migrants by the Relief and Rehabilitation Commissioner as domiciles. Furthermore, in September 2020, the Official Languages Bill passed under section 47 of the Reorganisation Act that has made Urdu, Kashmiri, Dogri, Hindi, and English – the official languages of J&K. Previously, Urdu was the sole official language of J&K, that too for over 131 years. The Minister of State for Home G Krishna Reddy said that introduction of the other languages was the demand of the people of J&K. Many Kashmiri politicians believe that all these changes especially extending domiciles and introduction of Hindi as one of the official languages in J&K are draconian steps to change the demography of J&K and the new laws are pre-emptive measures to block whatever decision the future J&K legislative assembly may take.

The District Development Councils and the Way Ahead

In October 2020, the Centre had approved amendments to the J&K Panchayati Raj Act, 1989. These amendments enable the establishment of all the three tiers of Panchayati Raj Institutions –Panchayats, Block Development Council (BDC), and DDC in the Union Territory of J&K. Previously, the J&K local governance had two tiers. In the DDCs there are 280 directly-elected members in 20 districts of J&K. The elected representatives of the DDC will serve the public for a five-year term and supervise the functioning of Panchayats and BDCs.

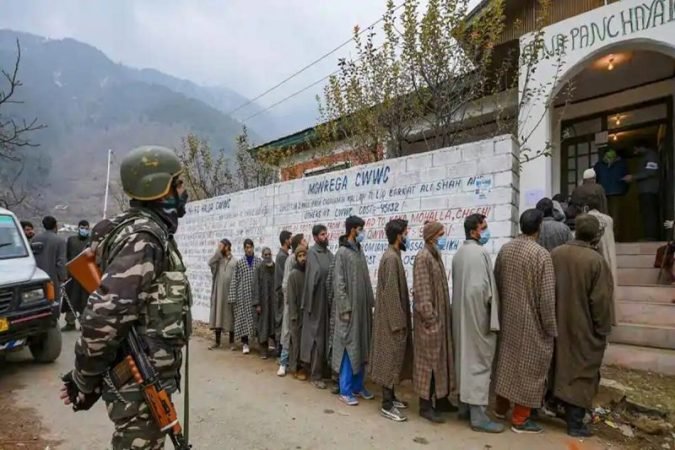

In the DDCs elections, the voters’ turnout was 51%. The election process that started on 28 November 2020 was completed in 8 phases on 19 December 2020. Stray incidents of stone-pelting and militant attacks happened in some places, but in general, the situation remained under control. The least voters’ participation was seen in Pulwama district, a hotbed of militancy and separatists. In the DDCs elections, the PAGD won remarkable seats and INC support has enhanced its seats share. Meanwhile, the BJP emerged as the single largest party and for the first time achieved a toehold in the valley where it attained relative success in the three districts (Bandipore, Srinagar, and Pulwama). The expected pattern of the divide between Jammu and Kashmir has emerged in the DDCs results. The BJP has won in the Hindu dominated districts in Jammu and the PAGD received unambiguous victory in Kashmir and the Muslim dominated areas.

The Takeaways

The DDCs elections and its satiable results have shown two positive signs: 1) The leaders of the Hurriyat Conference’s efforts to make people boycott the elections received lesser attention from the people. And, 2) the satisfying participation of J&K representatives and the participation of citizens in the political process amidst the rigorous Reorganisation of J&K.

It is a fresh start of politics in J&K and it has two ends.

Farooq Abdullah after the victory has stated: “Massive mandate to PAGD spells out people rejection of August 5 measures”. Whereas, the BJP claims that the result of the election, their emergence as the single largest party, and the performance of the independent candidates is a “resounding slap” by the voters on the face of the extremists, separatists, terrorists, and their supporters. Two narratives are threaping and both are getting their space, as it is said, “There is always room for at least two truths”.