The League is Dead, Long Live the League!

It has been a hundred years since the establishment of the League of Nations, the first world-wide intergovernmental organization that aimed at promoting world peace. As conflicts have a constructive consequence, the League was an outcome of negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference (1919-20) after the end of First World War (1914-18).

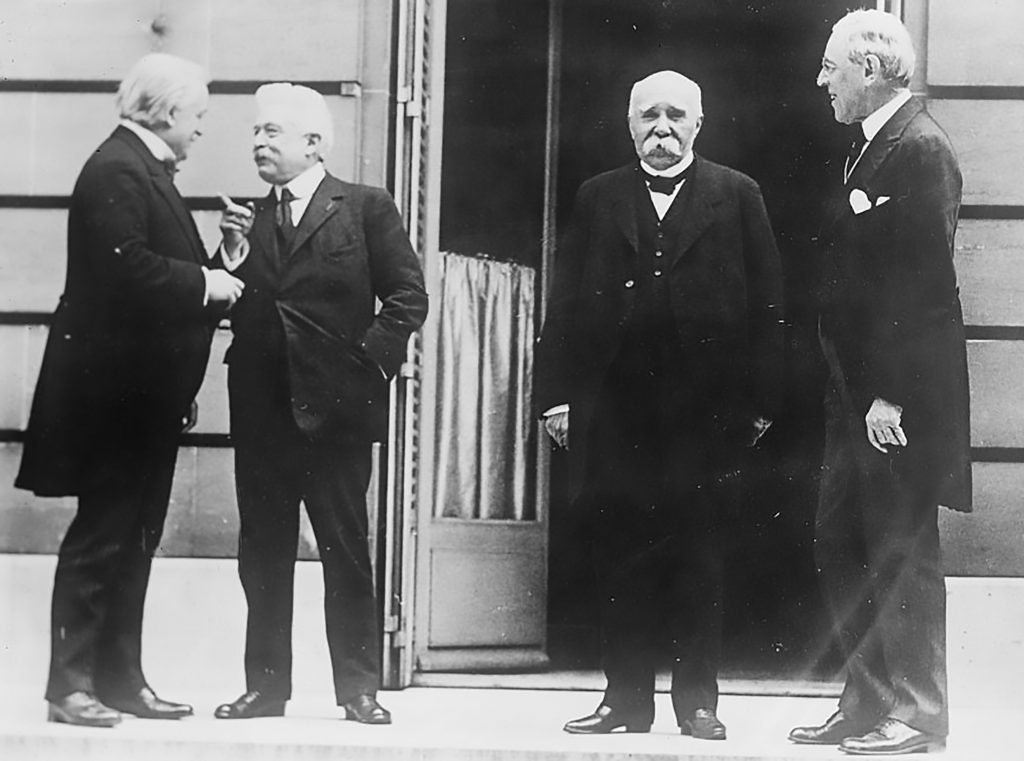

Before the establishment of the League in 1920, headquartered in Geneva, there were gradual attempts towards establishing an international organization. However, the devastating First World War shook the moral consciousness of the world and raised the urgency for an institutional mechanism to maintain the ‘status-quo.’ It was Woodrow Wilson, the President of the United States, who steered the ideation of the League. Ironically, the United States never joined the League due to the stiff opposition from the US Congress. Though the League ceased to exist after the Second World War (1939-45), its contributions have left an indelible imprint on the present-day international organizations. Some of the key contributions of the League are critically reflected here.

Firstly, the role of the League of Nations as an ideological and institutional precursor to today’s international organizations. Influenced by the ‘Wilsonian idealism,’ it was the League that laid the first foundation for the liberal international order. The League’s explicit advocacy for institutionalised democratic peace with free trade inspired the subsequent international organizations. The League was seen as the messiah of collective security and disarmament and pitched peaceful settlement of international disputes as an alternative to war; but, with the collapse of the League ‘system’ after the outbreak of Second World War, the United Nations (UN) and other organizations took the mantle. Lord Robert Cecil remarked, “The League of Nations is dead, long live the United Nations.” But in fact, it was the resurrection of the ideals that the League stood for – the political-project of the rueful Wilsonians in the Roosevelt administration to revive the spirit of liberal international order in the mid-1940s through a refined institution, gave birth to the United Nations. If one closely examines the ‘Covenant of the League of Nations’ (1919) and the ‘Charter of the United Nations’ (1945), the primary objectives of both organizations remained the same.

Various organs and agencies of the United Nations also inherited the legacy of the League. The UN Security Council was a more advanced version of the League’s Council. The UN General Assembly, where all its Member States participated with equal voting rights, drew its inspiration from the League’s Assembly. However, the fields of competence of the UN organs were well-defined, unlike the ambiguous organs of the League triggering structural paralysis. Other bodies of the League, the Permanent Court of International Justice and the Health Organization were restructured as the International Court of Justice and the World Health Organization respectively after the Second World War. The International Labour Organization, the brain-child of the League, was integrated into the UN system as a specialized agency in 1946.

Secondly, the League was the first to recognize the interplay of ‘power politics.’ The League’s Council gave primacy to the great powers – France, Italy, Japan and the United Kingdom – by granting them the permanent membership of the Council in 1920. Later, Germany (1926) and the Soviet Union (1934) got the status of great power in the Council. However, it was a reality that for an organization that thrived on Wilsonian idealism was not able to further carter to the growing aspirations of the great powers, forcing the powers to look for alternatives to advance their interests. For instance, during the Ethiopian crisis (1935-36), France and the United Kingdom took a ‘dual policy’ – they persuaded the League to action against Italy, the aggressor state, to appease the general public, but opened backdoor channels to negotiate with Italy. Ultimately, Italy annexed Ethiopia in 1936 and the role of the League as an instrument for maintaining peace and checking aggression, became redundant.

Hans J. Morgenthau states that the League had the potential to achieve more, had it aligned itself to the interests of the victors of the First World War – the League was, undoubtedly, a product of the victorious coalition. But, as Pierre Gerbet argues, the League alone cannot be blamed for its failures; it also indicates the weakness of the great powers to use the League as a tool to pursue their interests. The League’s vibrant and dynamic successor, the United Nations, became a foreign policy instrument for the great powers in the post-World War era; whether it’s the United States during the Iraqi Invasion (2003) or Communist China in the ongoing COVID19 pandemic.

Finally, the League illustrated the ability of an international organization to expand its role and methods in dealing with inter-state issues. Not merely as a political entity, but also as a player in socio-economic fronts. In the political sphere, the League’s multilateral diplomacy failed as the great powers undermined its existence, as seen in the case of the Ethiopian crisis. But the traditional diplomacy neither averted the possibilities of a world war; perhaps, this becomes the reason for the resurrection ‘collective security’ doctrine through the United Nations after the Second World War. The League was, however, credited for the peaceful settlement of disputes between smaller nations such as the Aaland Island disputes, Corfu case, Vilna disputes, etc.

In the socio-economic sphere, the League played a substantial role in addressing the issues of refugees and minorities, promoting economic and trade cooperation, protecting the rights of workers, women and children, tackling the menace of drug-trafficking, advocating global health and enhancing international mobility. The League’s advocacy in these terrains inspired various regional and international organizations of today – it can be even traced to the essence of the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2015-2030.

In conclusion, though the League of Nations existed merely for twenty-five years, its contributions to the development of present-day international organizations are indispensable. As an ideological and institutional precursor to today’s international organizations, as a vital part of power politics in the first half of twentieth-century and the earliest player in the socio-economic domains of the world, the history of the League is an important chapter in the study of international relations. The League is dead, but its spirit continues to survive, even after a century since its inception.