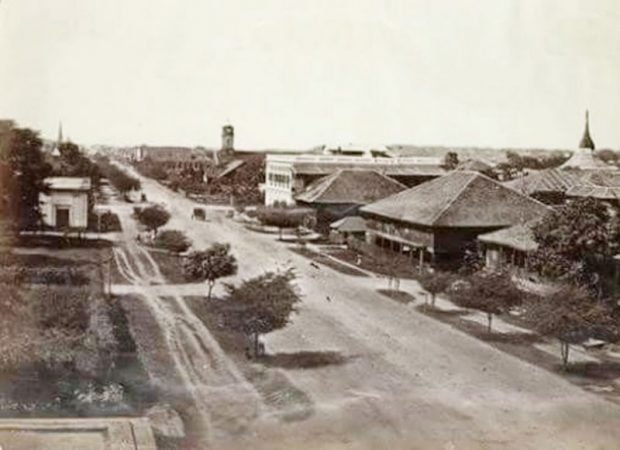

British Era- When India and Burma Were Together

Myanmar’s criticality for India has been variously defined, mostly referring to the “shared historical, ethnic, cultural and religious ties.” In real terms, both countries share a 1643 kilometre-long land border. A large population of Indian origin people, estimated to be in the range of 2.5 million, lives in Myanmar. Four of India’s north-eastern states, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, and Mizoram, are geographically connected to Myanmar. India also shares the strategic waters of Bay of Bengal, including the area of strategically important Andaman and Nicobar islands where the two closest Indian and Myanmar’s islands are barely 30 kilometres apart. Myanmar’s ports provide India with the shortest approach route to several of India’s north-eastern states. Since 1997, when Myanmar became a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), it also provides India with welcome geographical contiguity with the Asia-Pacific region. Myanmar, being China’s neighbour, also provides India a transit route to southern China.

History

India and Myanmar relations have a long history of political, cultural, religious and social interaction. Burmese civilization is closely linked with Indian civilization. Burma came under the influence of classical Hindu civilization from ancient times. And in the past, the relations between Burma and India developed through trade, culture, language, etc.

The connection between India and Burma began well before the British conquest. The Arakanese Kings had close contact with India in the 14th century. Burmese king Bayinnaung (1850– 1881) attacked and subdued the present day Manipur of India. After the British occupation, the two countries became a part of the British Empire. Burma was ruled by the British as a part of British India till 1937. The British brought numbers of Indians to Burma during its rule to join the public services, police and the military. Indians were used in large numbers as a part of the British colonial troops during the three Anglo-Burmese wars in 1824-26, 1852 and 1885. After the wars, they were employed to garrison the country. The Indian population in Burma on the eve of the Japanese invasion in 1941 numbered over 1.1 million and in 1931 Indians represented 7.5 percent of the total population of Burma, with a large number of them living in Rangoon. On the morning of independence on 4 January 1948, there were some 300,000 – 400,000 Indians living in independent Burma. The association of the two countries under British rule created a common understanding and they cooperated in their common struggle for independence. The Indian National Congress (INC) was sympathetic to the Burmese nationalists. In its Resolution on 27–28 March 1931, the Congress declared: “This Congress recognizes the right of the people of Burma to claim separation from India and to establish an independent Burma State or to remain an autonomous partner in a free India with a right of separation at any time they may desire to exercise it”.

After the separation of Burma from British India, the leaders of the struggle supported each other’s nationalist movement against British imperialism. Burmese leaders closely watched the Indian independence movement, especially in its last stages. While Aung San was appointed as Vice President of the Executive Council in Burma, Jawaharlal Nehru was in the same position in India. The Indian government placed at the disposal of the Burmese Government Sir N.B. Rau, one of its outstanding specialists on constitutional questions to help Burma’s work when it was drafting its constitution. On the eve of the independence of India and Burma the two countries grew closer. Dr Rajendra Prasad, the then President of the Constituent Assembly of India, declared at a meeting of Rangoon citizens on 5 January 1948, “Free Burma could always count on India’s assistance and services whenever she needed them”.

After that, the biggest bone of contention between the two countries was the fate of the People of Indian Origin (PIOs) who were being treated as foreigners despite having lived in Burma for generations. The Burmese government took a number of measures to strengthen the economic interests of the Burmese, such as forbidding foreigners from buying land. Nehru insisted on compensation for the Indian Citizens but soon reverted to the Nehruvian policy of not pushing Indian interests by claiming special privileges for Indians in Burma in order to maintain good relations between the two countries. Indo-Burmese relations were close during the first few years after independence and both Nehru and U Nu were leaders in the creation of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Both countries signed a Treaty of Friendship, which was to remain in force ‘forever thereafter’ if neither side gave notice of its desire to terminate it six months before its expiry after five years. However, after the 1962 coup, relations came to a standstill, despite the 1643 km long border India and Myanmar share. As trade between China and Myanmar increased, trade with India declined. In true Nehruvian idealist tradition, India ignored its eastern neighbour due to the undemocratic regime that had taken over. Relations improved slightly during the 1970s and 1980s with both countries trading official visits with Indira Gandhi visiting Rangoon in 1969, Minister of External Affairs, A. B. Vajpayee in 1977, Ne Win visiting India in 1980 and Foreign Minister Narasimha Rao reciprocating in 1981. Rajiv Gandhi’s visit in 1987 was the first one of an Indian Prime minister in almost 19 years. Relations deteriorated dramatically again when in 1988 India sided with the pro-democracy uprising and offered sanctuary to Burmese dissidents. It was only in 1992 that New Delhi decided to break the deadlock and start with a policy of ‘constructive engagement’ with the military regime. But it was only with the advent of the BJP led NDA government that things really began to change.

But if Burma had not been separated from India in 1937, the politics around independence in the late 1940s or 1950s would have been very different, The condition of almost all its ethnic groups would be better off, including the Bamar, who would be free to participate in the affairs of their own state, as well as that of a larger nation. But India and Myanmar still continue to make efforts to nurture their bilateral relations.