US must defend Cambodian democracy in 2023 as it did in 2013

There is, in terms of democratic principles, no difference between Cambodia’s national elections of July 2013 and those scheduled to take place in July 2023.

Such elections are either free and fair, or they are not, in which case they are a waste of time and money. In January 2013, the US State Department said that the fact that long-time opposition leader Sam Rainsy was still exiled from Cambodia, and barred from taking standing as a candidate in the election, called into question the legitimacy of Cambodia’s democratic process.

The US stance played a part in pushing Prime Minister Hun Sen to request a “royal pardon” which allowed Sam Rainsy to return shortly before the elections in July 2013. Independent observers noted that those elections were marred by systematic irregularities, and Sam Rainsy was not allowed to stand as a candidate.

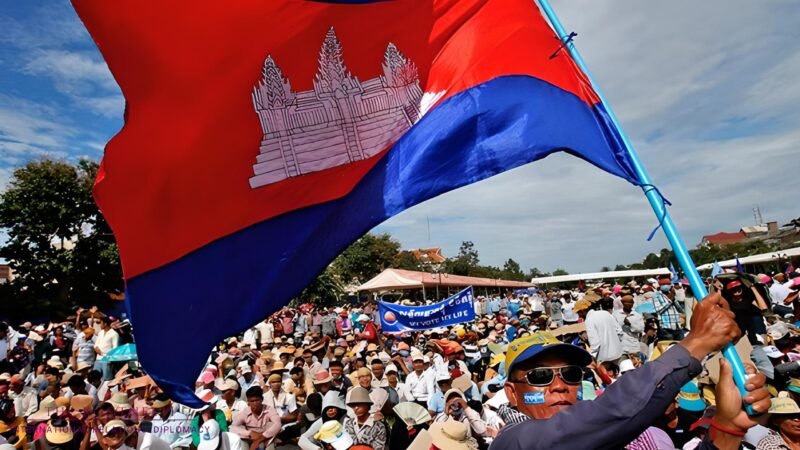

Yet the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), which had been established only the previous year, still scored 45% of the votes. This was not a one-off: the CNRP score of 45% was repeated in the local commune elections held in June 2017.

Lots of water has passed under the bridge since 2013. Hun Sen knew that the local election score in 2017, as well as opinion polls commissioned by the ruling party, pointed to a decisive CNRP victory in the 2018 national elections, which no amount of vote rigging would be able to cover up. He was determined to destroy the CNRP at any cost.

Sam Rainsy believed it was possible that the CNRP could be saved if he stood down as leader, which he did in February 2017, handing over Kem Sokha. Two amendments to the electoral law designed to eliminate him from the political scene were passed the same year.

The CNRP was dissolved by order of the politically controlled supreme court in November 2017. The ruling Cambodian People’s Party won every single national assembly seat in the 2018 elections. Kem Sokha was arrested and spent a year in jail on a spurious charge of treason for which no evidence has ever been produced. His “trial” has still not been concluded and he still has not had his political rights restored.

Sam Rainsy was forced out of Cambodia and now lives in Paris, with airlines having been told that they won’t be allowed to land in Cambodia if they accept him as a passenger. He attempted to return in 2019, but Thailand acceded to Hun Sen’s request not to allow him to fly there to prevent the possibility of a land border crossing.

Cambodia’s politically controlled courts meanwhile have continued to rubberstamp a long list of convictions against him. These include a life sentence for treason for promising in 2013 to protect the rights of indigenous peoples. An agreement signed by Sam Rainsy on indigenous rights simply reproduced articles from the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Further, a Cambodian constitutional amendment of 2021 forbids people with dual nationality from holding high office. This was tailor-made to suit the fact that Sam Rainsy holds French as well as Cambodian citizenship.

Hun Sen has also sought to break the opposition in financial terms. The property which Sam Rainsy and his wife Tioulong Saumura , a former deputy governor of Cambodia’s central bank, owned in Phnom Penh, and which served as the CNRP’s headquarters, was simply expropriated to pay the damages claimed by Hun Sen in a libel case.

Despite all this, and with Kem Sokha still without his political rights, Sam Rainsy is still the acting president of the CNRP, living in forced exile in Paris. The Cambodian people who voted for the CNRP in 2013 are now older and wearier and in many cases are in prison or in exile, but still have the same aspirations for democratic change. What has happened in the intervening decade is that Hun Sen’s regime has deployed an arsenal of means to remove his opponents from public view, and to shut down any possible space for free political debate.

Is such an onslaught enough to make the US and other Western countries forget about Cambodia? Some encouragement can be drawn from the fact that German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier went to see Kem Sokha while visiting Cambodia in February. The country is small, but allowing dictatorship to become embedded anywhere has far-ranging implications. Vladimir Putin calculated that the West talked a lot about freedom and democracy but wasn’t really willing to do much to back it up. The military junta which overthrew a democratically elected government in Myanmar in 2021 was clearly emboldened by the consistent ability of Hun Sen to repress his opponents with impunity.

Cambodia also has greater regional strategic importance now than in did in 2013. China has established a naval base at Ream, which extends its military capabilities. The arrangement suits both sides fine. China needs a compliant junior partner with port access within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Hun Sen can count on Chinese funding and military equipment to crack down on his opponents with no questions asked.

It’s clear that Hun Sen has full faith in his repressive methods and sees no reason to change them unless pressured to do so. His decision in February to close the Voice of Democracy, one of the country’s last independent media outlets, signals that he has no intention to allow any semblance of an environment conducive to genuine elections this year. Hun Sen in 2013 faced pressure from the US and many other democratic countries to allow at least a semblance of free and fair elections. That pressure urgently needs to be revived and amplified, with coordinated visa sanctions and asset freezes against the leading figures in the regime an urgent necessity.