China’s Double Standards and the UN Sanctions Regime

It is now more than 50 years since the UN General Assembly negotiated its first anti-terrorism convention. And almost 30 years ago the UN Security Council (UNSC) imposed sanctions against Libya for sponsoring acts of terrorism. The UNSC had adopted resolutions 1267 in 1999 and 1333 in 2000 which impose duties on states to prevent and suppress the financing of terrorism. The UNSC designated Osama bin Laden and associates as terrorists and established a sanctions regime to cover individuals and entities associated with Al-Qaeda, Osama bin Laden and/or the Taliban wherever located. But it was the attacks of 9/11 led to a flurry of UN measures to confront the terrorist threat, and the regime has since been reaffirmed and modified by a dozen further UNSC Resolutions, with sanctions being applied to individuals and organizations in all parts of the world.

The international economic sanctions region established by these resolutions has been characterised as the sole vehicle for truly global action against terrorism. The Council also extended the sanctions on Al Qaeda, which were originally just focused on Afghanistan, to all parts of the globe, vastly expanding the list of individuals and entities against whom the 1267 sanctions regime would be applied. Targeting individuals, rather than a specific State, marked a qualitative change in the UN Security Council’s sanctions policy. These so-called ‘targeted sanctions’, or ‘smart sanctions’, were introduced in a number of Security Council resolutions directed against individuals and entities allegedly associated with the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. Resolution 1390 enlarged the reach of the sanctions to any person associated with the Taliban, Osama bin Laden or al Qaeda. The special feature of the Taliban/al-Qaeda sanctions is that ever since Security Council Resolution 1390 there was no longer a territorial link to Afghanistan, and individuals of any nationality residing anywhere in the world have been listed. To date, pursuant to resolutions 1267 and 1333 approximately 699 individuals and 253 entities have been placed on a list known as the consolidated list and their assets are required to be frozen by member states.1267 imposes a limited air embargo and a funds and financial assets embargo. States are obliged to freeze funds of sanctioned individuals/groups.

Despite its importance in combating global terrorism, the Security Council’s asset freeze program has reached a critical juncture. Of late, increasingly fewer names are being submitted for designation under resolutions 1267 and 1333 and terrorist-related assets are no longer being frozen. As a result, terror organisations retain ample funding to sustain their operations and finance deadly terrorist attacks. Based on objective measurement it can be said that the UN counter-terrorism sanctions program appears to be failing. Senior counter-terrorism officials are less enthusiastic about the economic sanctions regime than ever before.

Recently while speaking at the Security council session on ‘Threats to international peace and security caused by terrorist acts’ (August 22) Permanent Representative of India to the United Nations, Ruchira Kamboj said that the credibility of the United Nations’ sanctions regime is at an ‘all time low.’ She was sharply critical of the U.N. Secretary General’s report on terrorism that had, in its section on threats in Central and South Asia, referred only to ISIL-K, and not to allied groups that target India, which India has been providing information on. Stating that the “selective filtering of inputs from member states is uncalled for,” she added “the linkages between groups listed by the UNSC such as the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and the Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) pose a direct threat to the peace and stability of the region.”

India’s angst is completely justifiable. As a consequence of the persistence of terrorist threats, India ranks as the 7th most terrorism-affected state in the world. Although various forms of terrorism have threatened India’s national security the use of terrorism as an instrument of foreign policy or state-sponsored terrorism is the foremost security threat. India has been reluctant about supporting the imposition of sanctions on sovereign states, but not in its use to fight terrorism. In 2011, against non-state actors India voted in favour of SC resolutions 1988 and 1989, establishing two distinct terrorism sanction regimes for ISIL (Da’esh), and Al-Qaida Sanction Committee and the Taliban Sanction Committee. Consequently, India has tried to list and delist individuals and entities in various terrorism-sanction regimes.

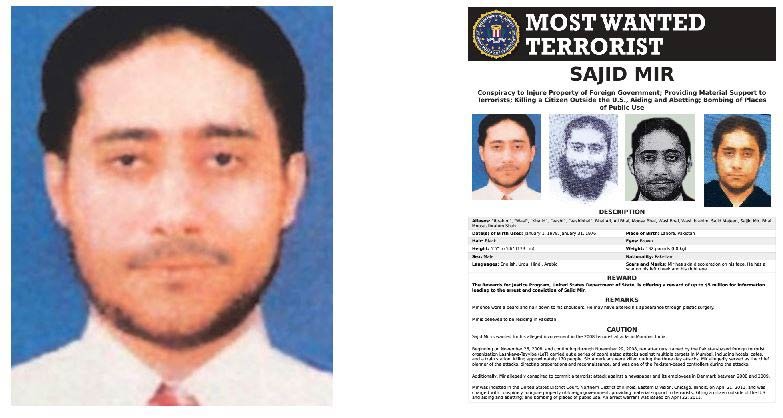

Recently, China has for the third time blocked an attempt by India and the United States to place Pakistan-based terrorist Lashkar-e-Taiba’s commander’ Sajid Mir, on the UN Security Council’s 1267 list. The planner of the 26/11 Mumbai terror attacks Sajid Mir was initially declared dead by Pakistani authorities in December 2021, and then as the date for the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) scrutiny came closer, he was suddenly arrested in April this year and his speedy trial was conducted within three weeks. The fact that for fourteen years Pakistan took no action against Mir a top terror operative indicates that he was considered a asset for a proxy war against India. Now when he was convicted and proceedings were being held to place him on UNSC’s sanctions list, China Pakistan’s closest ally blocked this move. This happened as President Xi spoke at the SCO meet in Samarkand about the need for concerted action on terrorism by the eight members of the grouping.

Weeks before this China had placed a technical hold on the proposal to list Abdul Rauf Azhar, deputy chief of the terrorist group JeM and younger brother of Masood Azhar. Mastermind of hijacking of IC 814 aircraft to get his brother Masood Azhar released from the Indian jail in 1999, and designated as a ‘global terrorist’ by the US in 2010 Rauf is currently the self-styled deputy chief of JeM. Despite the fact that a video of Abdul Rauf Azhar complimenting his cadres for an attack on IAF station in Pathankot in 2016 was also uploaded on a website in Pakistan, which India shared with Interpol, China placed an unprincipled hold on Rauf’s asset freeze.

China’s use of veto is not new as on four earlier occasions in 2009, 2016 and 2017 and 2019 too it had vetoed such initiatives. Earlier in 2019, when India had been trying to list Masood Azhar, chief of Pakistan-based terrorist outfit Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) involved in Parliament and Pathankot attacks under the Al-Qaeda and Taliban sanctions regime. Proposed by France in the Security Council, the move to list Azhar was supported by Russia as well but China put a technical hold on it. Following a series of behind-the-curtain negotiations, China has put aside its technical hold in May 2019 resulting in the listing of Masood Azhar. The US agreed to the proposal after India stopped importing oil from Iran.

Sanctions if applied diligently are an essential tool in the fight against terror financing. While the sanctions regime may not be lastingly constraining it does help reinforce the counterterrorism norm and foster international cooperation. More importantly, sanctions have a stigmatising effect by signalling to the local population that their future did not lie with such persons or entities. The sanctions against Sudan and Libya were phased out in 2001 and 2003 respectively after both ended their sponsorship of terrorist groups at least partly in response to the sanctions. It is important to record the cases of Sudan and Libya as these cases demonstrate that sanctions can prove to be an effective tool against States sponsored terrorism at least in those cases in which the economic damage and loss of prestige outweigh the benefits that a state believes it derives from involvement in terrorist activities. In Afghanistan, even though sizable financial assets were frozen, sanctions against the Taliban did not lead to any policy change in Kabul. Financial sanctions contributed to a significant weakening of Al Qaeda from 2005 – 2011.

But does the UN counter-terrorism sanctions program appear to be failing? Financial sanctions have also lost their effectiveness as Al Qaeda’s financing no longer relies on wealthy donors but on criminal enterprise and coercive taxation in areas where terrorist groups control territory, as in Syria.

Further, 2009 onwards the Security Council’s practice of reviewing requests for delisting from sanctioned individuals or entities, resulted in the removal of dozens of individuals and entities from the sanctions list. This practice was adopted after rights bodies criticized efforts to cut off all sources of direct and indirect support to terrorists and terrorist organizations because of its alleged impact on the families of those sanctions.

But most disappointingly, China has repeatedly been placing holds and blocks on listing requests without giving any justification. China has utilised its position in the UNSC to place proposals on ‘technical hold’ on the excuse that further time is required to examine them. The “hold” remains for six months and can be further extended by three months. During this period, it can anytime be converted into a “block,” thereby, ending the life of the proposal. Its repeated stalling of listings of Pakistan-linked terrorists have been China’s way of rewarding Islamabad. Beijing has consistently shown its willingness to use its diplomatic resources to defend Pakistan’s longstanding policy of sponsoring militant groups at the international level. According to Siegfried O. Wolf extensions of the technical hold on India’s listening application, flimsily arguing that there are “different views” in this matter, “are not merely a ‘hidden veto’ but show Beijing’s clear support for certain Pakistan-based terrorists.”

Inter-linkages between terrorist groups, cross-border operations including terror financing networks, propagating ideologies of hatred through ‘modern platforms such as social media, cyberspace and exist in parallel worlds alongside us’ have certainly left no country aloof from the impact of terrorism. Under these circumstances as the UNSC’s sanctions regime’s counter-terrorism efforts themselves appear subsided, and states are unreasonably using veto powers questions regarding its effectiveness have assume greater prominence. Unless significant measures are taken to hold states accountable for their failure to comply with their duty to freeze terrorist assets the anti-terrorist financing sanctions regime will cease to be relevant in the fight against global terrorism. India has rightly demanded that the “practice of placing holds and blocks on listing requests without giving any justification must end”.