What is Strongman Polity in China?

As in any country, a country’s past shapes its current character, and China is no exception. Until 1911, China lacked a foreign ministry. Prior to 1911, the Ministry of Rites was in charge of international policy. As a result, it is possible to conclude that traditional values are deeply buried in their thinking and are permeating their behaviours. This monarchical tradition has also been reflected in the current ruling polity of China where Jingping shapes the political character of the emperor like state. The civil society equates Xi with a godlike disposition.

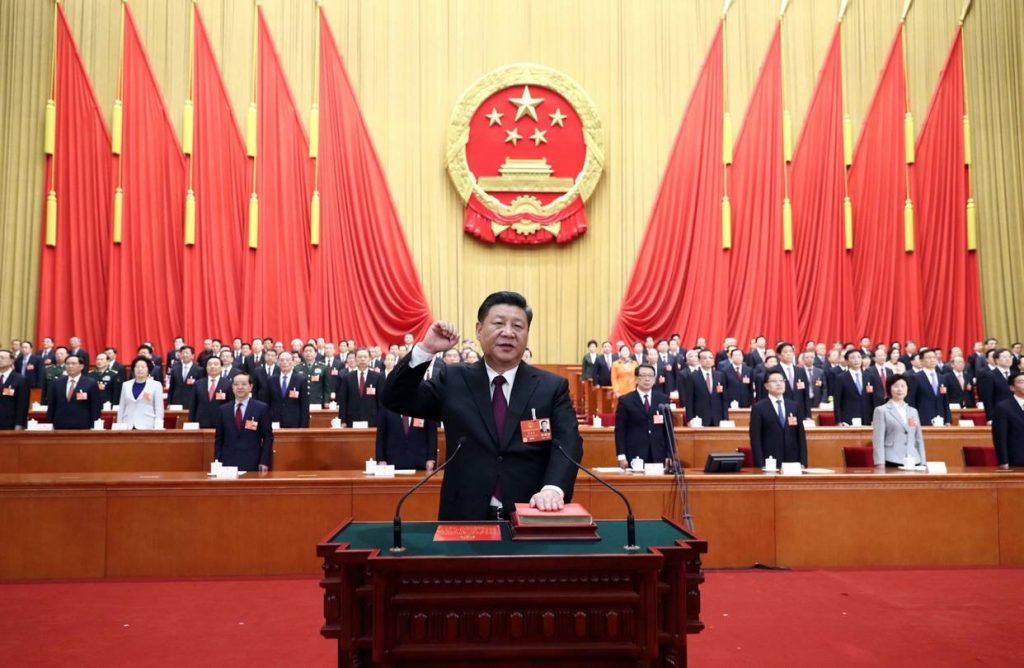

After the National People’s Congress voted decisively in favour of a constitutional amendment that allows President Xi Jinping to continue in office indefinitely, he is now the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong which is another red line in China’s growth as the world’s preeminent force. Xi Jinping is currently not only the president of China but also the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC).

For quite some time, there have already been allusions that Xi will be re-elected once his current term ends in 2023. Xi was named “the core” of the leadership in 2016, a term he shares with former Presidents like Mao Tse Tung, Deng Xiaoping, and Jiang Zemin. Nevertheless, He was been given the title lingxu by two big periodicals. This term refers to a leader of the greatest calibre, as opposed to just being a leader or lingdao, which he shares exclusively with Mao and Deng.

Xi Jinping holds the position of a strongman inside the People’s Republic of China (PRC). But what defines a Strongman polity?

An authoritarian political leader ruling over a state’s polity is known as a strongman. Strongman rule is defined by political scientists as a type of authoritarian regime marked by autocratic military dictatorships, as opposed to the three other types of authoritarian rule: machine (oligarchic party dictatorships), bossism (autocratic party dictatorships), and juntas (oligarchic military dictatorships).

After becoming the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in November 2012, Xi took decisions that have made him the most powerful man in the world today. He became China’s president for a long time and has steadily eradicated opponents inside the CCP since then, amassing great influence. Xi has essentially achieved all of the necessary characteristics of a dictator i.e. ruling indefinitely. In 2016, he was named commander-in-chief of the People’s Liberation Army, and he has direct responsibility over the People’s Armed Police. Not even Former President Mao Zedong had the opportunity to do so even at his zenith.

The strongman polity is made up of several hues, which reflects Xi Jinping’s character. For instance, alternative viewpoints are difficult for the strong man to consider. This is especially true when it comes to themes like democracy and alternate thought processes. Recently, with a view to claim external sovereignty, China has stifled voices of democracy in the protests in Hong Kong which has resulted in a British judge’s resignation from the city’s court. Jinping’s rhetoric has also displayed uncertainty when he has stated ‘Common Prosperity,’ a new catchphrase in the People’s Republic of China from August 2021. Which has caused dreads and worries among the masses of the corporate class?

While Xi Jinping remains China’s undisputed paramount leader there are reports of stifling dissents within the party as well. Wang Huning and Liu He, two of Xi’s closest aides, have been sidelined. Wang, a member of the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) in charge of ideology and propaganda, appears to have taken the fall for the Xi personality cult. Liu, the Politburo member in charge of economics and commercial ties with the United States, has been chastised for Beijing’s failure to reach an agreement with Washington on a trade truce. This shows that Xi has solidified his position as the party’s undisputed leader by instilling his own ideas and ideology into the party’s charter. Xi Jinping’s ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’ should be utilised to “arm the entire party, educate the people, and drive forward work,” according to a 2018 party keynote address.

Chairman of the National People’s Congress Li Zhanshu, a long-time Xi loyalist, coined a new term for the strongman Xi, referring to him as the party’s “eternal core.” Li, who is also a member of the Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (PBSC), urged all cadres and party members to do everything possible to “ensure that party central authorities, with comrade Xi Jinping at the core, will have the power to yichuidingyin [call the final shots] and to dingyuyizun [resolve differences with utmost authority].” Li was also essential in cementing Xi’s Mao-like reputation when he praised him as the “leadership core of the party, military commander, people’s leader, country’s helmsman, and people’s pathfinder.”-

Conclusion

President Xi Jinping’s populist leadership of China has been a lesson in the skill of combining flexibility in tactics with ideological rigidity—all while pursuing the ultimate aim of increasing his own and China’s power. The domestic and international policies of Chinese President Xi Jinping are philosophically dogmatic and politically single-minded, and they are inconsistent with the realities of both contexts. In recent years, Xi’s increased emphasis on state capitalism, the abolition of presidential term limits, Cultural Revolution-style propaganda, the cult of personality, and forceful foreign policy have all looked to coincide with this impression.

Xi has combined rigidity in his overall strategy and aims without flexibility and compromise in his methods. Despite the fact that illiberal trends are key to Xi’s leadership, he has not shown the same level of policy inflexibility as his predecessor, Mao Zedong and has made a number of significant concessions. Promoting private sector growth through tax cuts and other measures, exposing the business climate to international enterprises, and granting trade concessions to the US are the manifestations of the same. Xi has also made steps to widen his power base, enhancing his image as the people’s leader by breaking away from his prior strong links with princelings—leaders from seasoned communist families.

Xi’s portrayals frequently exaggerate his power and authority, ignoring the fact that he confronts difficulties at home and abroad. His hegemony over the country’s leadership has neither protected him from criticism or pressure nor has it allowed him to impose his policies without opposition. An examination of Xi’s strategic shifts can shed light on where, how, and why he chose to compromise. Although some may argue that such revisions are a result of Xi’s inability to meet his objectives, this flexibility indicates a more agile approach toward governance. His broad strategic objectives may remain steadfast, but the methods he employs to attain them are not.

Global views of Xi’s leadership remain low as per a survey of 17 advanced economies. As per the pew Research Institute “Views of Xi continue to be widely negative” According to the report, half or more of people in Australia, France, Sweden, and Canada stated they had no faith in Xi at all.

Domestically, starting with the State Council, Xi Jinping has taken control of decision-making. The nominal head of government, Premier Li Keqiang, has been marginalised, and Xi has instead delegated authority to party institutions that he controls himself directly. The CCP rank and file, as well as government personnel, have been intimidated by Xi’s remaking of party-state structures and anti-corruption efforts. Xi’s leadership style has hindered decision-making at all levels of the bureaucracy and inhibited any initiative that cadres may have had in the past to seek policy solutions to policy challenges. Meanwhile, authority in the central bureaucracy and its line ministries has shifted to “the leadership core“: decisions must be made by Xi or his intimate courtiers. Xi Jinping certainly believes that his strongman leadership has strengthened China’s image.

Nonetheless, the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted and even aggravated vulnerabilities in Chinese practice and policy under Xi in all four domains covered—governance, economic policy, social cohesiveness, and international affairs. Xi’s leadership is going to remain prevalent in the time to come. We are certainly living in interesting times where strongman politics is shaping the polities of various states. In the context of Beijing, the Panda Diplomacy has been replaced by an aggressive style of wolf warrior style politics. Rajesh Rajagopalan, a professor of JNU has once mentioned Norms are shaped by power, to believe the same in China’s present scenario Xi is shaping the norms in his own favour.