Reforms needed in institutions such as United Nations represent larger humanity by including countries such as India

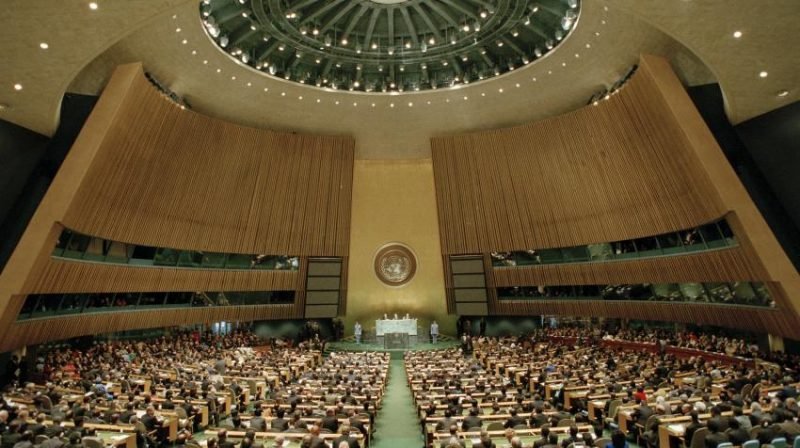

The United Nations was established following the after-effects of the World War II devastation and marks its seventy-sixth year in 2021. This comes at a time when the international institutions are burdened by increasing responsibilities in the domains of conflict management and the need to foster cooperation at a global level. The debate over the methods of strengthening and reforming the United Nations is thus more relevant than ever at this juncture. The United Nations is at a fork in the road. Unlike its predecessor, the League of Nations, it has survived and prospered in its seventy-five years as the world’s largest and most representative international agency. However, it is currently beset by a slew of problems, including gross underfunding, bloated bureaucracy, divisiveness, and geopolitical competition among the Security Council’s permanent members. These and other difficulties reduce its effectiveness and make it less relevant.

The reform of the UN has been on the agenda ever since the organization’s conception in 1945. The organization’s greatest challenge—one that has frequently prevented it from acting decisively on major global issues—is intransigence among the Security Council’s permanent members. As a result, reforming the Security Council to make it more inclusive, representative, transparent, and effective, as well as demonstrating better cooperation and consensus-building, is vital to the UN’s overall performance. This is also needed to reflect the changed power distribution in today’s world and tackle inaction by veto.

The Security Council, as it currently stands in terms of membership, functions, and powers, is unable to adequately respond to the world’s numerous problems. Despite the fact that its permanent members have shown little interest in internal reform over the years, it is in the interests of other UN member states as well as civil society to continue to strive for it. As powerful countries drift toward unilateralism, populism, and nationalism at the expense of multilateralism and collective action, a united and forward-thinking Security Council is a requirement.

India has been at the forefront of demanding reform in the UN, particularly its principal organ, the Security Council, for decades, staking its claim as one of the world’s largest economies and most populous countries, with a track record in promoting a rules-based international order, and contributing to peacekeeping through UN forces. The UN was born in the crisis of the World War era, and the realities of that time can hardly be compared to the present. The UNSC’s permanent, veto-carrying members, chosen by virtue of being “winners” of World War II — the U.S., the U.K., France, Russia, and later China — can hardly claim adequate representation of the world’s leadership today. The UNSC does not include a permanent member from the African, Australian, and South American continents, and the pillars of the multilateral order, such as the G-4 group of Brazil, India, Germany, and Japan, have been ignored for a long time. There are other, more representative options available, and this has been the crux of the change fight. Furthermore, because the UN’s membership is deeply polarised, decisions are either not made or ignored. Frequently occurring divisions among the UNSC P-5 result in critical decisions being stalled. These concerns are highlighted in a year when the coronavirus pandemic has brought the world to a halt, yet the UN, UNSC, and WHO have failed to play an effective role in assisting countries in dealing with the outbreak.

What has been a thorn in the flesh for India is that, despite the dysfunctional power balance that exists, the UN’s reform process, which is conducted through Inter Governmental Negotiations (IGN), has not progressed despite commitments over decades. The UN has decided to “rollover” the IGN’s discussions, which are focused on five major issues: enlarging the Security Council, membership categories, the veto power wielded by five Permanent Members of the UNSC, regional representation, and redistributing the Security Council-General Assembly power balance. It’s reassuring that the United Nations’ 75th anniversary declaration, which was approved by all member countries this week, commits to “improve the United Nations” by “instilling new energy in the talks on the Security Council’s reform.” Those remarks will only be realised if the UNSC’s permanent members see the UN’s grave danger and support the reform process, which will necessitate a significant amount of effort.

Since its inception, there have been six key reforms that the UN has undertaken. They are as follows:

1997 – Kofi Annan announces his plan for United Nations reform with two reform packages: ‘Track One’ and ‘Track Two’.

2004 – Two models proposed for expanding the Security Council.

2005 – Kofi Annan represents his most comprehensive reform and policy agenda with his report “In Larger Freedom”. The Peacebuilding Commission (PBC) is established.

2006 – The Human Rights Council replaces the former United Nations Commission.

2007-2016 – Reforms continue during Ban-Ki-Moon’s term with the launch of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and adoption of the Paris Climate Agreement.

2017-2020 – Reforms envisioned by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres have been ongoing which focuses on the UN’s peace and security pillar.

Although few are completely satisfied with the UN’s performance since its founding in 1945, an equal number of people believe the world would be a better place without it. The international system is essentially a collection of nation states, and major-power competition continues to drive world politics. In this scenario, UN reform, both structural and functional, will undoubtedly be a long and winding road filled with complaints and disappointments. It will, at the very least, create a public venue for governments to interact and seek cooperation, one whose legitimacy cannot be questioned. The overlapping shortcomings of many nations and international institutions in dealing with the coronavirus pandemic—both the failure to stop COVID-19’s spread and the inability to minimise its economic and political consequences. Another factor is the lack of action on the rising tensions between the United States and China.

In hindsight, a concert of powers may be the most fundamental prerequisite for an effective global institution. The Concert of Europe in the nineteenth century, the League of Nations after World War I, and the United Nations after World War II were all examples of this. Any international entity that lacks such coordination between key nations becomes dysfunctional or paralysed. The United Nations’ main objective should therefore be to prevent a new cold war between the United States and China, which would further divide the UN and the globe into rival camps. If the UN has to represent larger humanity, an essential prerequisite would be for it would be to devise an adequate response in order to tackle the challenges of climate change, arms control, poverty reduction, antiterrorism, arms control and disarmament, non-proliferation, and regional security.

Another important aspect that must be on the United Nations’ reform agenda is rebuilding its legitimacy from the ground up. The irony should not be lost on anyone that, at a time when proponents of the United Nations believe that multilateral approaches are more important than ever, faith in multilateralism is at an all-time low. When the globe rose from the ashes of World War II, it looked vastly different economically, socially, and technologically. The power balance has also shifted dramatically. Global institutions must adapt to these developments or risk losing credibility in the eyes of new participants, whether governments or citizens. They have often been targeted for being the cause of domestic problems. Despite the fact that this is not their fault, scapegoating would be significantly more challenging if these institutions were actively and openly demonstrating their merit.

Thus, working towards rebuilding its legitimacy must be numero uno for the United Nations. Effectiveness in terms of delivering better results such as public goods and ensuring greater representation of people and ideas from the South and East are the twin pillars by which this may be achieved. Meeting transnational challenges must be the primary area of focus for the United Nations and this is clear when one considers the difficulty in unilateral resolutions. Thus, the United Nations must ensure that it redoubles its efforts in order to ensure a higher level of human cooperation and endeavour.

To remain relevant, the world must evolve in both strategic and functional ways. It is also vital that the United Nations embraces the diversity of regional actors aiming to aid national governments and international institutions in maintaining the global order and achieving peace. It will only be able to meet the UN Charter’s primary purpose of preserving future generations from the scourge of war by adapting and evolving with the passage of time.

The UN’s collective power must also be synergised with its efforts in ensuring greater representation of non-security council countries. Its charter is a visionary document, and it has stood the test of time for three-quarters of a century. The UN remains one of its kind in providing a platform for initiating dialogue and action. However, long term reforms of the UN will require a tremendous amount of time, effort, money, and leadership. It will also demand a new agreement between the UN and the general public, as the UN’s legitimacy and power will become increasingly reliant on a sense of ownership. Individual states no longer have the ability to identify problems, formulate policies, and implement change in today’s complex environment. It needs the participation of a diverse set of players, including organisations, grassroots organisations, corporations, and local governments. Getting inclusivity right and switching to a fairer governance style will be critical in weathering power politics and delivering for everybody.

References:

i) “India’s Effort to Reform the United Nations Security Council Demands a New Mindset.” The Diplomat, thediplomat.com/2021/01/indias-effort-to-reform-the-united-nations-security-council-demands-a-new-mindset. Accessed 26 Dec. 2021.

ii) “UN Reform Is ‘the Need of the Hour’: India Premier.” UN News, 26 Sept. 2020, news.un.org/en/story/2020/09/1073862.