Misnomer of military ‘masculinity’: A case study of Nanjing massacre

In conservative, patriarchal societies, a binary of ‘effeminacy’ and strident masculinity often imprints itself upon the State and its (potential) subjects, highlighting the violent psycho-sexual archetypes underlying most forms of war and conflict. This article poses an enquiry into Japanese military brutalities in South-East Asia in the years leading up to the Second World War.

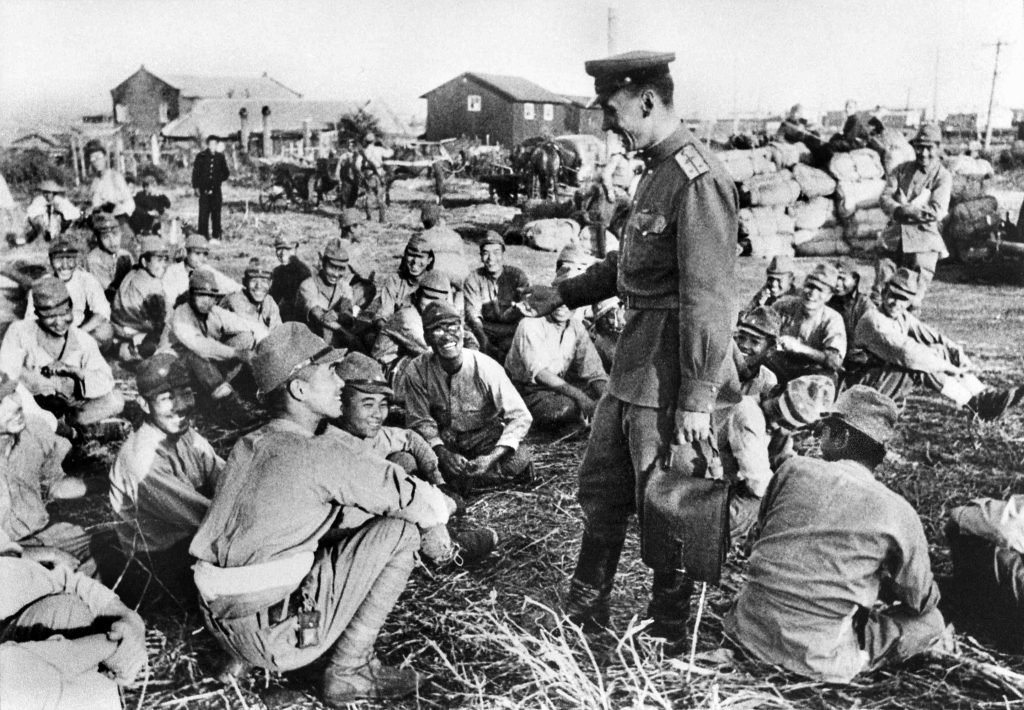

Japan’s cross-Pacific rampage is a seldom mentioned secret of modern history. Nations of the Near East cowered before the Japanese army, their land and lives savaged in seconds. When the armed forces of Nihon-koku rode astride, death and mutilation were certain to befall. The unabashed apathy, brutal mockery of the dead, and spectacle of man’s cruelty against man are history’s blackest nights milled into obscurity, confined within tomes and shut over. It is to be noted, however, that these tales of terror aren’t polaroids of the past, but living, breathing specters of today, hanging overhead the victims and subsequent generations of their families.

The Nanjing Massacre

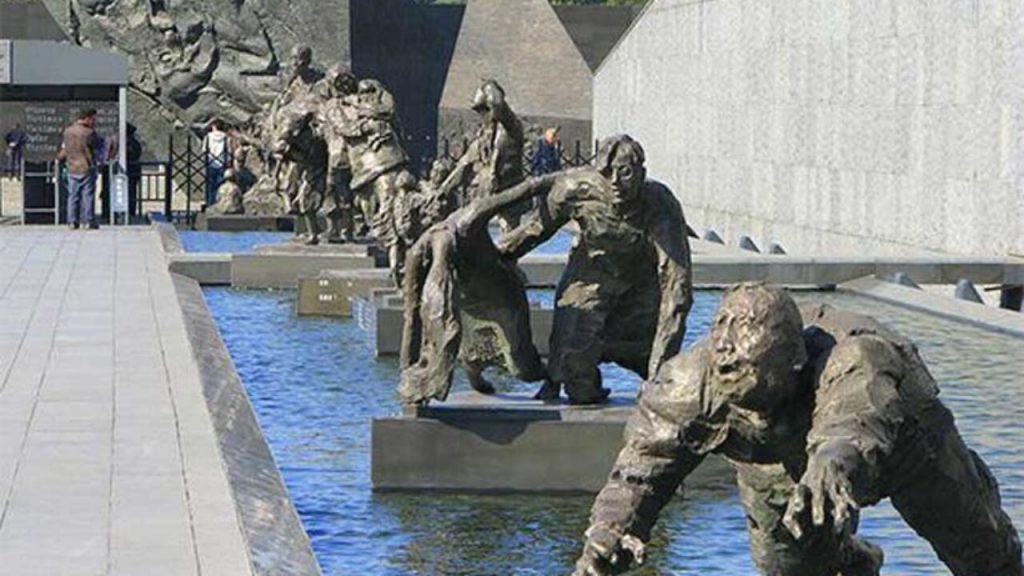

Mid-December marks a poorly suppressed memory for modern China: The Massacre that befell Nanjing in 1937, probably the deepest of gashes in Sino-Japanese relations till date. The then Capital was brutalized beyond recognition by Japanese imperial forces over the course of a single month. While an ongoing law suit demands liberal indemnity, apology, and amends for over 300,000 civilians affected, justice evades the threshold of the ‘daughters of Nanjing’- women ageing beneath the pall of incomprehensible violence, some of whom were barely toddlers to begin with.

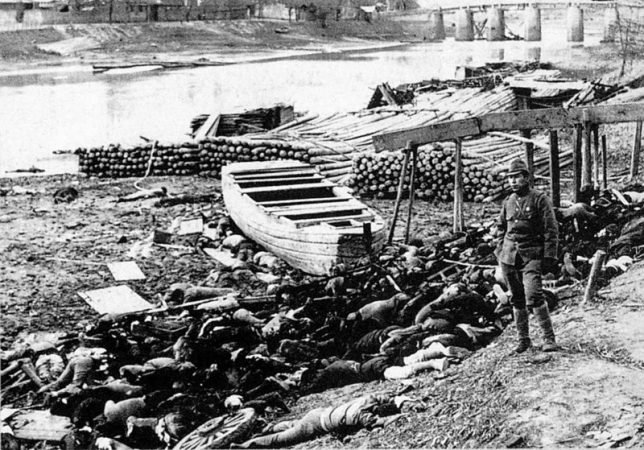

From the very outset of their march, the imperial forces of Japan left no stone unturned in terrorizing Chinese civilians, only heightening their brutality with each new acre transgressed. The horrors wrought reached a deafening crescendo with the siege of Nanjing on 13th December, 1937. While the shuddering details of mass rape and murder that followed are too graphic to elaborate upon here, eyewitness accounts from the period deserve a passing mention in order that the scale of devastation may be impressed upon the reader.

Pregnant women were cut open and unborn fetuses gored by the dozen, the soldiers went door-to-door looking for little girls and carried them off in the dead of the night, female students were kidnapped, never to be heard of again. Those who did come back told tales of unimaginable horror. One might as well assume that not a single woman of Nanjing, nor a single household, was spared the Japanese onslaught. Retellings of mass shootings and butchering piled like the bodies on the streets.

Chinese forces had been withdrawn from Nanjing in November itself by Chiang kia-shek, then what glory were the Japanese soldiers seeking in humiliating even the dead who lay at their feet? Some contested narratives from the time denounce soldiers who treated the massacre as a game, competing amongst themselves over who could brutalize more. Undoubtedly, the writer is hard-put to give words to this forgotten holocaust.

Psychoanalyzing The Tragedy

Near about a century on, scholars continue being baffled by the tragedy’s implications for potential depravity of human psyche. Nanjing makes for a heartrending study in why war and conflict seemingly give free lease to violent sex-crimes that become preposterous notions in times of peace. The genesis of such mind-numbing brutality lies in an aggressive extension of the patriarchal state’s notion of ownership, such that even a newborn is considered personal property, violable as pleased by the State’s arms. In this regard, War may be viewed as a phallic symbol in itself, a quest for State-masculinity to assert itself.

State violation of human rights is an occurrence commonplace enough to be of no consequence to the average demographic of citizenry whose antecedents have been in power since times immemorial. War elevates this violation a thousandfold, finally awakening the deadest of moralities to the human toll involved. It is only in armed excesses that the plight of weaker sections becomes overt to those given over to blind privilege.

As stated before, War’s implicit sanction to crimes of such a nature highlights a binary of ‘effeminacy’ against the State machinery’s assertive masculinity. ‘Femininity’ is a term made synonymous with ‘weakness’ in common parlance. In perpetuating violence against the ruling class’ (potential) subjects, the Japanese armed forces used rape as a tool to ‘effeminate’ or ‘emasculate’ them by making them incapable of protecting their community’s honor that was perceived to rest with the women of Nanjing. Insidious notions of gender binary and honor came into play that fateful December, making Nanjing a notorious addition to the annals of war and its breach of all psychological frontiers.

Also, if ‘effeminacy’ connotes cowardliness, then no other terminology would better correct the misnomer of military ‘masculinity’ in the light of such historical evidence as the Rape Of Nanjing; it is high time that ‘slurs’ such as ‘effeminate’ be reclaimed by victims, nay survivors, in antagonism to perpetrators of State-sanctioned violent crime.

Consequences For Sino-Japanese Relations

It was decades before the Chinese psyche even began to comprehend the trauma of Nanjing. When history cuts too deep, verbalizing bloodshed takes an eternity. Thus fell a curtain of silence over the bleeding aftermath of Nanjing. Leaders of the immediate period following the war hardly referenced it under enduring Japanese pressure. Nevertheless, ‘The International Military Tribunal For The Far East’ was the first amongst many steps taken towards salving the wound.

Certain sections of Japanese politics outright deny the occurrence of the massacre at Nanjing, not unlike their better-known brethren in the West that denounce the Jewish Holocaust as fabricated propaganda. As many survivors of Nanjing are still alive, and therefore a major chunk of evidence comes from first person accounts, these sections find it easy to denounce lived stories of pain and humiliation. China’s aggressive foreign policy, a gross overcorrection for its century of humiliation at best, might make it highly convenient for by-gone powers of the region to buy such narratives that counter their own past apathy, but fails to adequately detract the fact of Japanese brutality. Elsewhere, Korean women, too, are demanding reparations from Japan over forced military prostitution. At some point the survivors will far outnumber the deniers.

In any case, Nanjing is a jarring bone of contention betwixt modern-day Japan and China. In 1995, the Emperor, and the Prime Minister of Japan issued a public apology for the war crimes committed. A compensation, long overdue, would be a small step enroute atonement, but is yet to come. Chinese mistrust of Japanese only grows by the year and tt would not be a miscalculation to say that Japan, too, has something to fear in China’s rise as a superpower and its ever-burgeoning hegemony in the South-China Sea for no wound runs deeper than one acquired in legacy

Japan’s unspeakable atrocities in the century past might as well come back to haunt it in a new world order.