Decoding the Divided Trilogy and Post-American Afghanistan

Every Developed or developing country has its shared interests and the Indian role and activities in Afghanistan are far from incompatible with American goals and interests. As Special Envoy Richard Holbrooke stated in his April 2009 visit to the region,

“Everyone in this part of the world should recognize that for the first time since partition, India, Pakistan and the U.S. face a common threat and a common challenge, and we have a common task.” He added, “Now as we face a common threat, we must work together. We know it’s going to be difficult, but the national security interests of all three countries are clearly at stake.” The task that lies before American policymakers is to put aside past concerns, however legitimate, of Indian ties to and support for various communist regimes and focus on the current convergence of interests.

The main impediments to greater US-Indian cooperation in Afghanistan

Indo-US Relations seem likely to be a combination of their low expectations of what can be achieved positively, as well as a recognition that any Indian role (even in areas such as development assistance and the like) will often be perceived as nefarious by Pakistanis, risking a backlash from Islamabad. But there’s still a useful common agenda going forward.

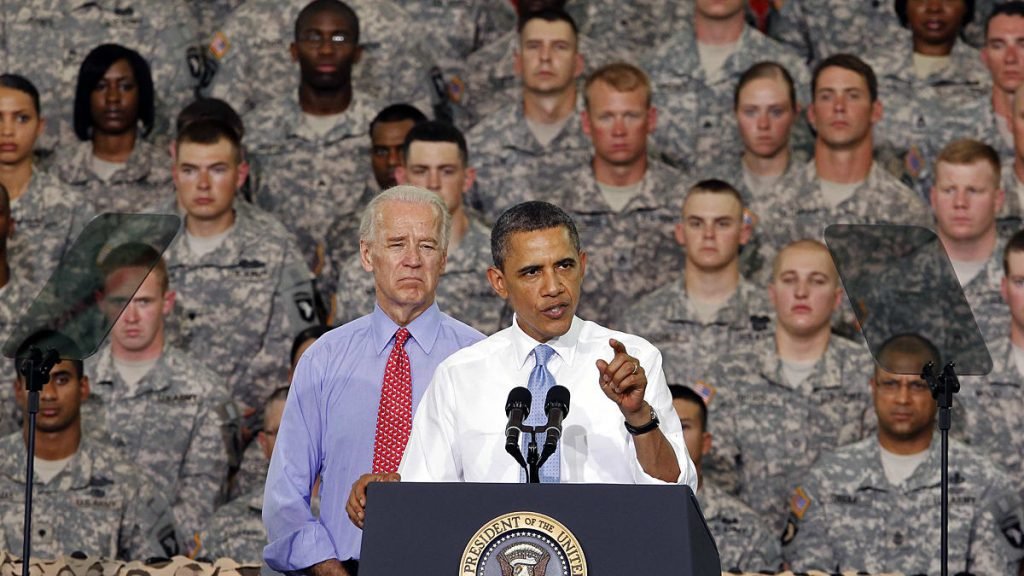

As the Afghanistan war reaches its 15-year mark, it’s important to notice that President Barack Obama is that the first two-term U.S. president ever to wage a single war in a single country for the entirety of his tenure in the White House. It has undoubtedly caused Obama considerable frustration, angst, and heartache throughout much of his presidency, albeit he originally considered it a war necessarily and a noble cause.

Results, alas, were disastrous. The insurgency is still strong, and the government is ineffective. Over 2,000 Americans have died there, the majority of them under Obama’s leadership. Obama wrestled with his decision to launch a comprehensive and well-funded counterinsurgency operation for the country, which he did in general.

Pakistan’s Security & Economic Interests in Afghanistan

Pakistan welcomed the formation of the new unity government in Afghanistan and therefore the signing of the BSA with the United States. However, given the long-term presence of US soldiers in Afghanistan, Pakistan is wary of the consequences for its own security (even in a non-combat mode. Counter-terrorism training and operations against Al-Qaeda and therefore the Taliban within the coming years will demand extensive intelligence sharing between the United States, Afghanistan, and Pakistan with probably continued U.S. reliance on drone warfare inside Pakistan’s tribal belt. Pakistan itself has been pursuing domestic counter-terrorism operations since June 2014 through Operation Zarb-e-Azb to combat local and foreign Taliban forces operating from North Waziristan.

However, the US has been wary of the objectives and successes of this operation. In this air of continuing mistrust, future intelligence sharing between Pakistan and the United States could be affected, especially because renewed drone strikes on militants inside North Waziristan might be viewed by Pakistan as inimical to its own fight against domestic terrorism. For decades, Pakistan viewed Afghanistan as a crucial part of its sphere of influence, shaping its intrusive foreign policy towards Afghanistan. However, there has been a “strategic shift” in Pakistan’s policy towards Afghanistan in recent years driven by three considerations. The Pakistan Policy Working Group recommended that Afghanistan must back a neutral relationship with India and Pakistan, in which it does not choose sides and rather calls for amicable relations with both.

Trump called out Pakistan, tweeting that the US had “foolishly given Pakistan more than US $33 billion over the last 15 years and they have given us nothing but lies and deceit, thinking of our leaders as fools and giving safe haven to terrorists”. By mid-2018, he reversed policy and authorized direct negotiations with the Taliban further adding to their international acceptance. By February 2020, the US withdrawal deal in return for safe passage was signed and presented to the international community as a peace deal. The process of legitimization was complete and the last favor the US did was to ‘persuade’ the Afghan government to release over 5,000 Taliban prisoners, adding to its marginalization.

This was the policy perplexity that Biden found himself trapped in.

India’s Security & Economic Interests in Afghanistan

In a speech at the 2014 BRICS Summit, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi once more reaffirmed India’s commitment to Afghanistan within the following words: “India will still assist Afghanistan in building its capacity; in governance, security and economic development.”

India–Afghanistan relations since the overthrow of the Taliban in 2001 are cordial and strategic. The United States, on the other hand, has been suspicious of the operation’s goals and results. While it was frequently overlooked by NATO planners in Afghanistan, who were afraid that further Indian involvement might encourage Pakistani nationalism. India has pursued robust relations with Kabul and therefore the latter has been responsive.

India is that the first country with which Afghanistan signed a Strategic Partnership Agreement, In October New Delhi has played a serious role within the Istanbul Process launched in November 2011, and its core focus has revolved around investments in infrastructure, mining, education, and small-scale industries. India has about $2 billion in investments in Afghanistan, compared to China who has around $3 billion and is the fifth-largest donor to Kabul after the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, and Germany. In other words, India has limited its efforts in Afghanistan to providing humanitarian assistance including food aid, infrastructure development, and capacity-building, including providing scholarships to Afghan students to obtain education and training in India.

US withdrawal from Afghanisthan – Pragmatism or a Facade?

Even though the US intervention ended ignominiously on President Joe Biden’s watch, there have been a series of cumulative mistakes by each of his three predecessors—Presidents Donald Trump, Barack Obama, and George W Bush— contributed to this outcome.

Biden came out with a defiant speech, defending both the choice to exit and also the way during which the exit was conducted. He stated that the Trump administration’s signing of the Doha Agreement on February 29 last year left him with the “option of leaving or escalating”

What Biden ignored was that after having called it ‘a bad deal’, he had retained Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad, the architect of the deal, within the same role. His own inclination had always been to exit and as Obama’s vice chairman, he had opposed the ‘surge’ but was overruled by Obama and therefore the generals.

Biden insisted that there was no way of doing a more orderly exit because had he started it earlier while the war was still happening, there would still have been a rush for the airport and it might have led to a crisis of confidence within the government, making it a difficult and dangerous mission.

He maintained, “I am not going to extend this forever war and I wasn’t extending a forever exit”. Biden insisted that there was no way of doing a more orderly exit because had he started it earlier while the war was still happening, there would still have been a rush for the airport and it might have led to a crisis of confidence within the government, making it a difficult and dangerous mission. He is, perhaps, right there in the evacuation only commenced after Kabul fell and President Ashraf Ghani fled the country on 15 August.

Biden apprehended two important lessons, “setting missions with clear achievable goals and staying focused on fundamental national security interests”. These are valid lessons, and he was pointing to the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom. Even while denying it, the US and the international community had embarked on a nation-building exercise in 2001 because Bush’s global war on terror demanded it. Preventing a return of the Taliban demanded building a new constitutional democratic state, or so the Americans believed. However, even as the Taliban found sanctuary and safe havens in Pakistan that enabled them to regroup and re-establish their financing mechanisms, the US got distracted with the war in Iraq from 2003 onwards.

The Pakistan ISI resumed their old game with the US, running with the hares and hunting with the hounds, emerging as the front-line state partnering with the US in Afghanistan while subverting US efforts by aiding and abetting the Taliban and the Haqqani network as they unleashed a spate of improvised explosive device (IED) attacks and suicide bombings in Afghanistan, aimed at undermining the Afghan government and drawing the US forces into a counterinsurgency from what had initially been a counterterrorism mission.

How would the next period be in the Post-American World?

The war’s not over. this is often what the subsequent phase seems like.

While the US has officially declared an end to its military operations in Afghanistan, military operations won’t really be terminated but will transition to a replacement phase. The US still retains vital interests in evacuating US citizens and coalition and Afghan allies, and in preventing additional terrorist attacks by al-Qaeda, etc. Both of those objectives, also as others, would require tons more work (both diplomatic and military), tons longer, and extra-national resources. The US also now features a lot of labor to try to prop up its alliances within the wake of the poorly executed withdrawal. This, too, would require new efforts if it seeks to navigate this dangerous new era in a way that protects American security and prosperity.

When the fighting ceases in Afghanistan, unlike in other locations, the war becomes serious. In the 1990s, the Taliban arose as an Islamist Pashtun group, and that DNA still exists today. It has regained power through armed methods rather than through diplomacy. Statements about forming a more inclusive and representative government are still hazy.

How does the Taliban deal with its main backer, the ISI, as well as other collaborators, such as Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State of Khorasan (IS-K), the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP), and others? How long till the fighting resumes?

Although Biden has brought an end to America’s “longest war,” peace in Afghanistan is still a long way off.