From ‘China Fantasy’ to ‘China Challenge’: The failure of China engagement?

China is neither becoming a democracy as Western expects nor overthrowing the world order in the near future

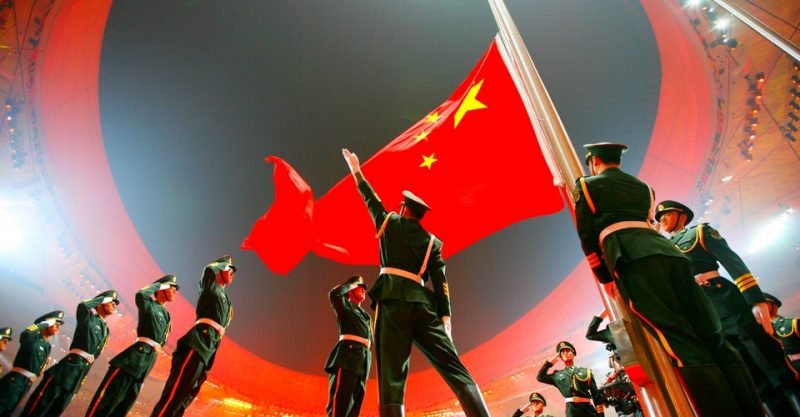

On 17 November, U.S. State Department issued a plan named The Element of the China Challenge laying out 10 tasks for the US to confront the rise of China and sustain the liberal international order and its role as the leading superpower. In the report, the harsh criticism of China has been sharpened by noting that “China is a challenge because of its conduct” and will “fundamentally revise world order”. Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson responded in the press conference, claiming that “this document is made by some who have Cold-War mentality in their brains. It fully exposed the Cold-War mindset…also these politicians’ fear, anxiety and twisted mindset towards a developing China. They want to revive the Cold War, but this attempt will be rejected by all peace-loving people around the world.”

China’s emergence has become a hotly debated topic in the U.S. foreign policy community over a few decades while the narrative of its rise has been shifted in recent years. Following the normalization of the Sino-U.S. relationship and China’s embrace of state capitalism and global markets in the 1980s, many Western elites believe that China’s economic growth and liberalization would lead to democracy eventually. From the 1990s to the 2000s, political leaders of the U.S. were optimistic about the opening of China’s political system and keen to engage China in the international system. This kind of assumption was identified as “China Fantasy” by James Mann who argued 14 years ago that China would turn out differently. In line with Mann’s belief, “China Threat” Theory has gained popularity among many scholars and hawk politicians, perceiving China as an economic, military, and ideological threat. Parallel to this threat discourse, the U.S dominant narrative framed China as a different partner that the U.S. could cooperate with and direct in the desired way.

The shift occurred in the Trump Administration that releveled its disappointment and frustration over engagement with China. Both Vice President Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo publicly declared that the hope for a free, open, and democratic China is “unfulfilled” and engagement is a “failure”. A similar narrative can be found in National Defense Strategy that officially referred to China as a “revisionist power” with the intention to “shape a world antithetical to U.S. values and interests” in 2017 as well as “a strategic competitor”, placing “the central challenge to US prosperity and security” in 2018. In addition, a series of actions taken by Trump Administration including the trade war, the ban on WeChat and TikTok, the closure of the Chinese consulate in Houston and acts to sanction Chinese officials conform to its confrontational stance towards China’s rise. These two sets of narratives represent conflicting and polarized assumptions, whereas China may fit neither.

Likelihood of democratization?

Either welcomed by engagement or hit by “China Challenge” narratives and approaches, China has shown little tendency to become an expected democracy. While it has made significant achievements in economic development, poverty alleviation and law, China is widely perceived by academics and politicians to have increasingly worse human rights records. Since 1972, it has been identified as “Not Free” by Freedom House Index and “has become increasingly repressive in recent years.” Regarding the level of political rights and civil liberties, Political Terror Scalethat explores the level of violations of physical integrity found that China from 1978 to 1988 belongs to “level 3” with “extensive political imprisonment, unlimited detention, with or without a trial, for different political views”, yet, after 1989, it has been considered to have worse performance as “level 4”. Similarly, this trend has been indicated in CIRI Human Rights Data Project from 1981 to 2011. In terms of governing, it is widely believed that the power of the President and decision-making authority within the party have been consolidated and centralized.

There are internal and external factors that continue contributing to little changes in democratization. Internally, The Chinese government has rank safety and security that are good for the economy as a high priority. With the complexity of economic growth, some citizens are developing grievances and political demands that lead to online dissenting opinions and even organized protests. In response, the government often resorts to approaches to maintain the status quo as well as resolve the unease at the same time. Democratization which could be accompanied by violence and instability is not an option. For example, the state-run media People’s Daily commentedin November 2019 as “the rule of law and social order have been severely violated. How can we talk about human rights and democracy?” Meanwhile, the most majority still favours the rule of the government. A long-term surveycarried out by Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center found that the citizen have very high satisfaction with the central government as 95.5 percent of respondents were either “relatively satisfied” or “highly satisfied” in 2016. Externally, there are few constraints and pressure from Western countries. Rather than imposing conditionality when offering aid and membership or threatening trade restrictions and sanctions to ask for better human rights practice and democratic government, Western businesses and governments have long been reluctant to take a tougher stance towards China due to increased commercial involvement. Thus, the Chinese regime is not going to open up in a long term.

Likelihood of a new international order?

As observed by many who agree with “China Challenge” or “China Threat”, China is expanding its participation and influence in existing organizations and creating new ones such as the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, the current “China Challenge” discourse may exaggerate China’s ambitions and abilities to overthrow the existing world order. There are two reasons why China cannot and may not plan to “fundamentally revise world order”. First, it has benefited from and contributed to the current international order. The key elements of the order include globalization, multilateralism, cooperation and development assistance which China has neither abandoned nor rejected. From the 1990s to the 2000s, China has received significant development assistance from UN institutes such as UNDP and UNICEF, as well as official aid from other countries including Japan, Germany, United Kingdom, Canada and France for poverty reduction, environment conservation and institution building. In the last decade, it has been continuously supported by 24 UN agencies through various programs to address challenges faced by the vulnerable and disadvantaged. In recent decades, China’s support for the United Nations (UN) has grown considerably. The second-largest contributor to the UN’s regular budget. Moreover, it lacks soft power to attract willing followers and create a new order. The current international order is premised on liberal political norms, which suggests that an alternative one may require a new set of norms. Although China to some extent has been different from the liberal elements of the post-war order, the alternative development model it represents is less likely to constitute mature values that can establish a strong alliance with other major and rising powers in a supportive international environment.

Indeed, China’s rise fell short of the expected modernization, causing concerns among the West. Neither engagement approach that wishes for democracy in China nor “challenge” narrative warning of threats China poses may effectively shape its rise and path. In a long period, it is very likely to remain its increasingly assertive role in the current order with the same political structure. Its relations with other major powers, particularly the US, will be featured with consistent tensions over different interests as well as occasional cooperation on shared global challenges.