The Philippine Revolution and role of Filipinas

In 2012 when the Philippines celebrated 113 years of Independence, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines bestowed the historical marker, for the very first time, to the Women Revolutionaries/ Filipinas also called as founding mothers who sacrificed themselves for the country’s freedom. The Philippine revolution, broke out in 1896 was against imperial Spain, was the threshold of three centuries of revolt and resistance against European intruders who began to colonise the island in the mid-sixteenth century, even the Americans participated in the conflict with Filipinos against Spain. However, in the early 1900s, the American denied Philippines to govern their country.

The western colonization, as maintained by the Filipino scholars, had degraded the status of women in Philipinnes. Before the arrival of Spanish imperialists, it was observed that the tribal women resided in the archipelago had an egalitarian status with men. The men offered with the role of Datu which made them ruler of the political realm while women got bequeather with the role of Babaylan or high priestess making them ruler of the spiritual realm which is equally important. Besides, the mainstream histories have barely recognised the contributions or even the presence of women Filipinas in the revolution. Christian Doran (1999), the scholar who wrote extensively on Filipinas and the Philippine revolution, reviewed selective English literature of the 1980s. She observed that influential works of Edwin Castillo and Linda Ty-Casper had either skipped the women from the revolutionary action or confined them to the traditional feminine role. For instance, in the novels of Linda Ty-Casper, The Three-Cornered Sun and Ten Thousand Seeds (1987) that specifically focuses on the revolutionary period, Donar analyses that the in the former women characters are weak. They are the secondary characters in the main action of the novel that did limited contribution in the revolution. The Three-Cornered Sun though depicted the presence of women in the revolutionary camp, the Filipinas got represented as clumsy, ineffective and constrained by the demands of the motherhood. The novel reinforces the stereotypes associated with the women affairs such as taking care of the family; frightened of warfare, blood or gunfire; becoming the sexual conquests for male in which the exploitative nature is left undiscovered. Lastly, the women revolutionaries got painted as their world revolves around the interest of families and their incapability to commit to greater or higher causes. Proceeding to the latter novel, Ten Thousand Seeds, Christian deciphered that it asserts on the traditional relations of masculinity and war. Ty-Casper in its two novels maintains that only men make the war while women are only subordinate to main actions. Henceforth, this explicates that the mentioning of women’s participation in the revolution wasn’t considered significant by the major historical work. In the public realm, it’s limited to occasional magazines and newspaper articles written by women journalists, unpublished thesis written by female scholars and few historiographical marginalised text.

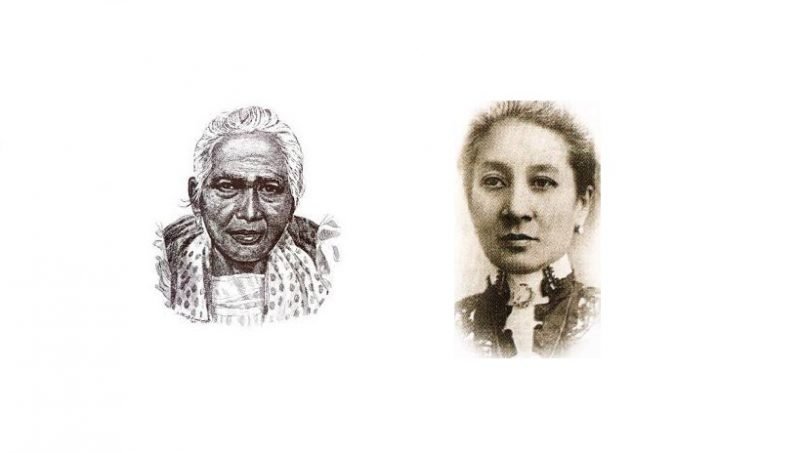

The Filipinas revolutionaries performed a variety of roles such as messengers, soldiers, nurses, spies, strategists and so on. But, during the revolutionary period and beyond, their diverse roles got discriminately minimized, obscured or ignored. One of the Filipina, Melchora Aquino got honoured with the national fame as she supported the revolution. Tadang Sora, her other name, was a poor old lady who provided the maternal aidings by harbouring the revolutionaries, feeding them and nursing the wounded Filipino soldiers in her store. She was to Guam for six years when the Spanish authorities arrested and interrogate her, from then onwards she got bestowed with the title “Mother of the Revolution”. Some Filipinas were excelling in battlefields. The most distinguishable were Agueda Kahabagan and Teresa Magbanua who led the troops in the combat and achieved the rank of general in the revolutionary army. It was observed that General Aguedo impressively dressed on battlefield mostly in white: “Astride a horse, she held a revolver in her right hand and the reins and a dagger in the left. Fearlessly and with head bigh, she charged against the enemy. She rallied the others to do the same, and many did give up their lives valiantly (Alvarez 1992: 161)”. The Filipinas dominated spaces that normatively considered as men realm. It was evident in the Red Cross association of Philipines – the Asociacion Filantropica de la Cruz Roja (also known Junta Patriotica de la Cruz Roja) wherein Hilaria Aguinaldo got appointed as the first head of the association. It was founded to support the revolution by inciting and co-ordinating the humanitarian work by women also to collect funds for war and treatment of wounded soldiers. For this purpose, Aguinaldo organised the charity bazaars, benefit concerts and other functions to collect contribution either in form of money or goods.

One of the most noticeable Filipina was Marcela Marino Agoncillo because of her association with a national symbol, the flag as she and five other women revolutionaries using their “feminine” skills of stitching, sewed the flag as asked by her husband – the lawyer, who was in the opposition of Spanish regime. Later, this flag became a model for the other flag made by Patrocinio Gamboa which got hoisted in the inauguration ceremony of the revolutionary government. Since the flag needed to get transported to Santa Barbara from Jaro, where Gamboa sewed the flag, she disguised herself and her intentions to safely pass through the Spanish guards. Thereby she gained the espionage talent undertaking various intelligence mission for the revolutionary causes. The contribution of women revolutionaries was not only squeezed to logistics. They provided significant intellectual and ideological work through their literature which has often remained unnoticed such as they published poems in revolutionary publications like El Heraldo de la Revolucion and La Independencia (CS).

From the deliberation of the women revolutionaries in the Philippine nationalist movement, the Filipinas had engaged in all the revolutionary phases and wide range of essential tasks. In the nationalist cause, they were an integral part in planning, initiating and execution of the Philippine revolution against the Spanish Imperialists. This research article, unfortunately, couldn’t cover-up many women revolutionaries who are considered as founding mothers. Notwithstanding, this article tries its ablest to give the representation to these women revolutionaries that got sidelined from the mainstream histories/biographical texts but, simultaneously, resisted their eradication from the history also to shed the light on the conventional approach of studying revolutions/war/conflicts that are mostly associated with masculinity.