A Profound Reading on Legality of Nine-Dash Line

The Nine dash line is an unspecified and ambiguous maritime area claimed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) out of its spurious claims in the South China Sea. “Beijing stakes claim to most of the region and at the heart of this claim is the U-shaped ‘nine-dash line’ that includes as much as 90 per cent of these waters.”This line was originally known as 11 dash line which, after Mao’s decision to wave claims over Gulf of Tonkin, renamed as the nine-dash line.

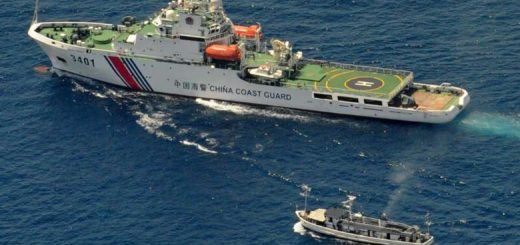

Neither diplomatic nor legalistic perspectives could decipher Chinese avowal over the Nine-Dash line, which is often invariably articulated and misconstrued in international discussions. This misconstruction is the reason for intimidation of neighbouring states which fear that China could claim sovereignty not just over water but also over the land and associated seabed.

This article is a legal analysis of the Chinese claim of nine-dash line and ventures to ascertain how they are inconsistent with international law. The author also sheds light on the possible legal outcomes that the future may hold for China.

The Legal Perusal of the viability of Chinese Claims

The broadcast of dispute started in 2009 when Malaysia and Vietnam jointly submitted their intention to a commission to establish outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm. China objected to this move and wrote a letter to UN Secretary-General claiming that “it has indisputable sovereignty over islands in the South China Sea and adjacent waters”. Chinese contention over “sovereign rights” was too ambiguous to be digested and the adjacent states had instantly objected to this claim. In a separate note, China claimed Spratly islands to be a part of PRC under Article 121 of United Nations Convention on Law of Seas (UNCLOS) which meant it has exclusive rights over territory, an economic zone and adjacent waters.

China claims the waters on “historical’ basis. In international law, in order to ascertain historical rights, the claimant has to satisfy that there is a common and genuine perception of impugn territory being under the country’s possession since time immemorial. Here China faces problems as it was never contested a part of China before china became a communist nation in 1949.

In international law, there is a very famous perception that says “land dominates the sea” and seas per se are not subject to any form of occupation. It is the sovereignty over land and subsequent claim over waters in the form of exclusive economic zones or other zones that constitutes sovereignty overseas. China can look from another perspective where a state with relatively new claims satisfies that some other states also recognize its “righteous” claim over the disputed area. A precedent is found in Anglo-Norwegian Fisheries case where Norway contented its baseline system to be acquired by the British and this claim got legitimacy from courts of other states. In order to satisfy the International courts and Tribunals, the claim must be clear, concise and consistent and it should be explicitly and correctly known to other states.

In Philippines v. China case, the tribunal decided on the assumption that China’s claim over the waters is concerned with historical rights and not historic titles (China claimed an exception under Art 298 of UNCLOS, discussed in my previous article at The Kootneeti).

Proofreading whether Chinese contests Sovereignty

Chinese misarticulated claims have made it debatable whether China’s pretext of “historical rights” is the same that of “sovereign rights” under UNCLOS. China has never officially vented the exact position of its claims and has been intentionally silent as the future may provide the apt time for asseveration. However, some Chinese scholars do write frequently over these rights. They have shown records from fishing ascendancy to maritime expenditures (often from Ming dynasty) but didn’t crosscheck these with the ancient documents of neighbouring countries; scholars from these countries invariably denied any such proofs. This makes it difficult for China to make the world believe of a common perception in the region about the Chinese ancient rights as required to provide in international law.

China never told the world whether it claims the Nine-Dash line as a part of the territorial sea or internal waters. The word “sovereignty” used time and again by China to buy time and create an ambience of ambiguity which may prove beneficial in the long run. UNCLOS which allows such historical bay under “special circumstances” would find difficulty as the nine-dash line in no case would be claimed inside twelve kilometres, which constitutes the territorial sea. This being the case, China’s claim is a manifest dispute over sovereignty.

Article 311 of the UNCLOS provides that if any “historical claims” intrude into the EEZ of another country or are in any kind of dispute with the continental shelf and exclusive rights of that other country, then EEZ and other zones would always prevail over such rights to decide the sovereignty. States have sovereign rights over the resources in the waters (Article 56) and the coastal states have the exclusive right to harvest the natural resources. Thus, even if China’s historical rights claim over the resources within the nine-dash line are valid, UNCLOS would always supersede and coastal states would seize the treasure. This was the dictum in China v. Philippines ruling. Therefore China either has to prove and satisfy how its claims in the nine-dash line should not get overridden by UNCLOS or satisfy there was a common perception in other states from time immemorial. If such states do not indulge them in the proceedings, such silence shall be counted in China’s favour.

Concluding Remarks

In 2011 China, in a note verbale, asked for an exclusive economic zone for Spratly islands which should accordingly be counted as an island. This was denied by the arbitration tribunal in the South China Sea which ruled that Spratly is not suitable for human habitation and therefore is a “mere rock”. The judgment wrote, “They obviously could not sustain human habitation in their naturally formed state; they have no freshwater, vegetation, or living space and are remote from any feature possessing such features”.

As discussed above, some islands may be denied the islands status and an economic zone; some may get an EEZ to a certain extent. This is yet to be decided whether other states are going to acquiesce or they will challenge the Chinese claims. In this respect, China’s diplomatic ties could play a huge role; China’s continuous silence is a sign of buying time and pitching in at the correct time.

In international law, UNCLOS would always prevail over any kind of rights. If China wants to move through the legal machinery, which she is certain to do except for an unjust encroachment, it has to shorten the limits of claims so that they may not infringe over the sovereign rights (in EEZ) of other states. Chinese claim on “islands” clearly indicates the plan to ascend land and subjugate waters through the continental shelf and EEZs thereof.