Dreams in Doldrums: Indian Engineers Suffer in Kuwait from ‘Rotten’ Education System in India

The Kuwait Society of Engineers (KSE) has decided to withhold no object certificates (NOCs) for Indian engineering graduates that are alums of Indian colleges unrecognised by the National Board of Accreditation (NBA). This move has endangered the future of about 12,000 Indian engineers currently working in Kuwait. The plight of Indian Engineers in Kuwait shows the rotten education system in India.

Stranded in Kuwait

According to Indian engineers working in Kuwait, engineering degrees from several Indian colleges were once recognised but are now rejected because of the absence of NBA accreditation.

The KSE first raised the issue in 2018, when the re-verification of engineering degrees was undertaken, including interviews. In 2020, the process was repeated along with re-stamping by the Kuwaiti Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA). Again, after another two years, the Indian engineers were essentially harassed by the re-verification process again, requiring document verification by a third party. This time, KSE requires NBA recognition for the four-year engineering study programme. KSE needs “full time” to be mentioned in the documents like mark sheets.

The KSE continues to change the goalpost and harass the Indian engineers’ community by periodically changing its requirements.

India’s Engineering System and the Ensuing Ruckus

The education system in India, known internationally for generating some of the world’s most talented engineers, doctors, and chartered accountants, among other professionals, is undervalued in Kuwait, say the Indian engineers living there. Many countries, like Kuwait, value the education system in India but not the educational institutions themselves.

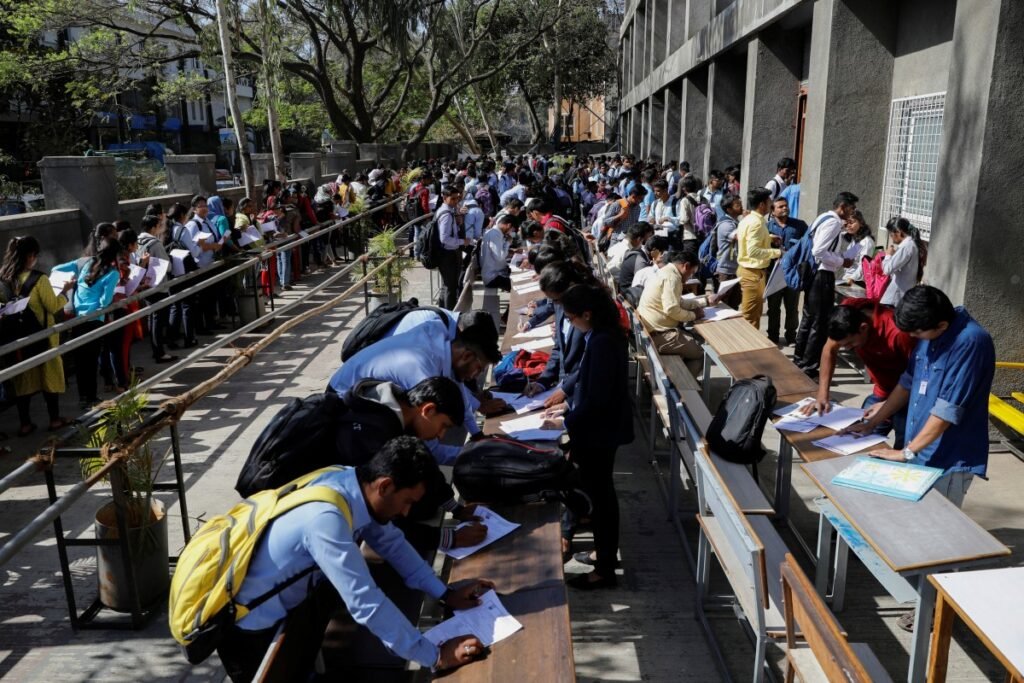

Like most non-Western countries, India faces the stigma of false degree certificates leading to third-party verification of the certificates issued by Indian Universities. This can be attributed to a variety of different factors. Given the national fascination with engineering, for every student that studies at an IIT or an IIIT or NIT, thousands of more end up at one of many private institutions. Not all engineering institutions are operated alike. An excessive number of substandard institutions operate without quality control and employ faculty members who do not meet industry requirements.

Further, the theoretical persuasion at engineering institutes is hollow. The primary tasks of a professor at such institutions are restricted to teaching. This severely impacts the research output of the nation as a whole.

The lacklustre research culture in India plagues even the top-notch engineering institutes. As a direct consequence of this fact, the IITs feature low on the global rankings. Research is an essential component of the academic world for several reasons, the most significant of which is that it enables individuals to put what they are learning into action, ensuring that their courses remain relevant. Sadly, not only is this shortcoming present in engineering, but it is also present across the board in the education system in India. Hence, the vast majority of inferior engineering institutions produce graduates without the essential skills required to be a part of a productive workforce. However, even the most significant institutions only produce trained labourers who can be good “corporate workers,” not researchers or innovators. This is the case regardless of the quality of the college.

Essentially, India’s bright graduates shy away from opportunities in the education sector because they were never taught in a way that helped them develop the ability to think critically or the abilities necessary to be effective educators. This is a direct result of the situation described above. In addition, they do not find academics interesting because, in their view, it is not a method of doing research and disseminating cutting-edge knowledge; instead, it is the tedious process of reciting information learned in a lecture while sitting in a classroom. The general quality of education is suffering from several causes, including but not limited to those listed above.

The entirety of the field of higher education grapples with a number of these challenges. Still, with regard to engineering education, these problems have grown to a point where they are more severe. In addition, particular issues are connected with engineering education. Some of these issues include an unbalanced development of engineering education, which results in certain sub-streams of engineering thriving at the expense of others; mismatches in the labour market, which are reflected in gluts and shortages; rising fees and individual costs; and the predominance of student loans.

All of these issues contribute to the fact that engineering education has its challenges. On the other hand, except for a few committee studies, there have been relatively few in-depth analyses of the most significant challenges and issues currently confronting engineering education. The absence of studies investigating the socioeconomic ramifications of growth, especially the nature of development, which would help to understand how the so-called “new middle class” creates new demand, stands out as particularly significant.