China steps up climate fight with emissions trading scheme

China launched its long-awaited emissions trading system on Friday, a key tool in its quest to drive down climate change-causing greenhouse gases and go carbon neutral by 2060.

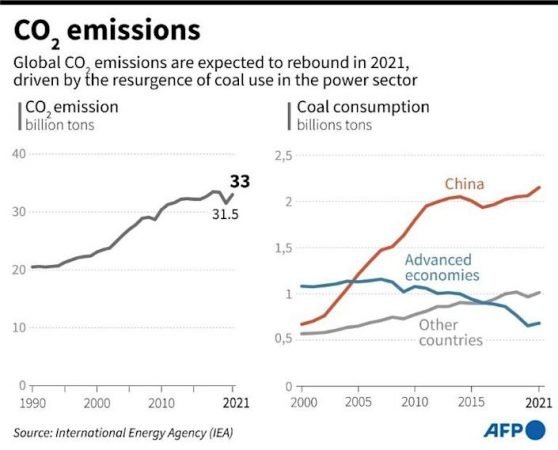

The scheme was launched with China, the world’s biggest carbon emitter, seeking to take a global leadership role on the climate crisis in the lead up to a crucial UN summit in November.

China has hailed it as laying the foundations for what would become the world’s biggest carbon trading market, forcing thousands of Chinese companies to cut their pollution or face deep economic hits.

The programme was launched just days after the European Union unveiled its detailed plan to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

However deep questions remain over the limited scale and effectiveness of China’s initial emission trading scheme, including the low price placed on pollution.

More broadly, analysts and experts say much more needs to be done if China is to meet its environmental targets, which includes reaching peak emissions by 2030.

China first announced plans for a nationwide carbon market a decade ago, but progress was slowed by the influential coal-industry lobby and policies that prioritised economic growth over the environment.

The scheme will set pollution caps for big-power businesses for the first time, and allows firms to buy the right to pollute from others with a lower carbon footprint.

The market will initially cover 2,225 big power producers that generate about a seventh of the global carbon emissions from burning fossil-fuels, according to data from the International Energy Agency.

Those power producers account for 30 percent of the 13.92 billion tonnes of Earth warming gases belched out by Chinese factories in 2019.

Citigroup estimates $800 million worth of credits will be bought for this year, rising to $25 billion by the end of the decade.

That would make China’s trading scheme about a third the size of Europe’s market, currently the biggest in the world.

The scheme was originally expected to be far bigger in scope, covering seven sectors including aviation and petrochemicals.

Low ambition

But the government “pared down ambitions” as economic growth took precedence amid the pandemic-induced slowdown, according to Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

“China’s coal, cement and steel production have all gone up as the government pours in billions of dollars to energy-intensive sectors to boost growth after the pandemic,” Myllyvirta said.

“Rules to limit emissions will disrupt this growth model.”

Another concern for environmentalists is the low price China is placing on pollution.

Opening trade at the market in Shanghai started off at 52.7 yuan ($8) per ton of carbon on Friday morning.

The average carbon price in China is only expected to hover around $4.60 this year — far below the average EU price of $49.40 per ton, Citic Securities said in a recent research note.

Free pollution permits given out at the start and token fines for non-compliance would keep prices low, according to analytics company TransitionZero.

However China has characterised Friday’s launch as just the first step.

The scheme will expand to cover cement producers and aluminium makers from next year, Zhang Xiliang, chief designer of the scheme, said last week.

“The goal is to expand the market to cover as many as 10,000 emitters responsible for about another 5 billion tons of carbon a year,” Zhang said.

Chinese state media have also pointed out the current version is already theworld’s largest market when assessed by the amount of greenhouse gas emissions covered, rather than trading value.

Other concerns about the scheme include that a lack of technical know-how and continued pressure from powerful coal and steel lobbies could slow down progress.

Local officials and companies know little about accounting for emissions or even the basics of climate science, said Huw Slater from China Carbon Forum.

And regions that rely on coal and carbon-intensive industries for growth have been slow to join the scheme.

“Officials are afraid that if they curb pollution too quickly it could cut jobs and lead to social unrest,” Slater said.