Ethnicising Citizenship: Laws, Violence and the Lhotshampa ‘Other’

State systems and their practices in the South Asian region have always shown a glimpse of their inherent ambition to achieve a homogeneous state based on ethnicity and religion. While almost all sub-regions have had their experiences with ethnonationalism amounting to the dismissal of minorities, the realities of it remain particularly relevant in South Asia even in the 21st century. As the history of genocides carried out in the name of religion and ethnic identities continue to remind us of the existing fault lines within the political systems, it also reveals in itself certain ideation towards defining citizenship based on ideas of majoritarian rule, which binds the otherwise diverse region. Using legal grounds to make citizens aliens in their own country, violently attacking minority groups and endangering their modes of sustenance that triggers ontological crisis threatening one’s identity and entire existence is a visualization endemic to South Asia.

This essay aims at exploring the contours of conflict between legal and ethnic spaces by taking up the case of Lhotshampa Refugee Crisis and the Nationality Law of Bhutan 1958 and Citizenship Act of 1985 that produced world’s largest refugee population per capita. The expulsion which began in the 1990s continues to remain unresolved even after two decades.

Politicizing Existence: Bhutan and Bhutanese

The journalistic romanticisation of the Himalayan region has resulted in producing a very exotic picture of Bhutan, often replaced with that of the last Shangri La. However, the region with all its mystified stories and Gross Happiness Index has also continued to rob the Lhotshampa population off its land, resources, rights and, expression resulting in their statelessness. The ethnic make-up of Bhutan accounts for Lhotshampas (inhabitants of the South), Sharchop (inhabitants of the East), and Ngalong (inhabitants of the West and/or The First Risen). The Ngalong are regarded as the first community to Bhutan to adopt Buddhism and enjoy historical precedence which translates into them being a politically dominant ethnic group. The language of Ngalongs’, Dzongkha has also been the national language of Bhutan since 1961. The Lhotshampas are of Nepalese descent and comprised a quarter of Bhutan’s population.

The Lhotshampa culture needs to be understood as a constantly negotiated construction. In addition to its internal contradictions deriving out of its Nepali and Bhutanese heritage, externally it has constantly been regarded as an ‘other’ culture against that of the native Ngalongs (also called Drukpa). This demarcation between self (Drukpa) and the enemy other (Lhotshmpa) intensified the conflict between the two communities and by extension between the Drukpa majority state and the Lhotshampa minority. Researchers like Michael Hutt, who has worked extensively on Bhutan and its state systems, has notably pointed out the attempts of the Bhutanese state to isolate the Nepali migrants to the southern belt, restricting them to either settle or purchase land beyond the south. The implication of such an action was completely unanticipated as Hutt argues that by restricting the Lhotshampas to the south of Bhutan meant blooming of population in the area which is also remarkably viable for economic growth and development which further induced fear and anxiety among the majority.

The entry of Lhotshampas into Bhutan as Nepali migrant labourers began in the late nineteenth century and they settled permanently during the 1950s. They soon developed a social system which was not a total emulation of a Nepalese Hindu culture but was distinct enough to not be submerged under Bhutanese culture which has Tibetan-Burmese influences. Consequently, migration continued as more political, social and economic reforms were being introduced and implemented. This movement across borders coincided with heightened ethnic consciousness that impacted the nation-building process of Bhutan. Legislative institutions, designing civil code and drafting citizenship laws are representative of these processes. More often than not, the state uses the legal apparatus to determine who belongs and who doesn’t, thereby making its discriminatory and violent practices official.

Borders of Difference

During the 1950s, Bhutan was traversing the path to nation-building by establishing institutions to tackle external pressures on its sovereignty as well as internal pressures for protection of rights notably from Bhutan State Congress formed by the members of Lhotshampa community in 1952. In 1953 National Assembly was formed which passed the Supreme Law in 1959. The laws governing citizenship was first passed in 1958 and revisions followed throughout the 70s and 80s with far-reaching and devastating implications. Citizenship laws reflect the intent of the state when it comes to interacting with ethnic and religious minorities and gives us a scope to explore the institutional ways through which a state renders its own people powerless, creating divisions and inflicting insecurity and trauma.

The Nationality Law of 1958 is the first legislation for granting citizenship and was supposed to grant full citizenship to the Lhotshampas. The law provided broad avenues for acquiring the status of a Bhutanese citizen. These were: by the virtue of being born to a father who was a Bhutanese national, through a petition to an official provided certain conditions of residence like owning land and being a resident for at least ten years and/or government employment for at least five years, and thirdly through marriage to a Bhutanese national. This act, in essence, solidified a legal category of a “citizen” which was absent before 1958. This also meant that by regulating citizenship, the national identity of a Bhutanese had also risen as opposed to distinct ethnic identities of Ngalong, Sharchop, and Lhotshampa. While the act didn’t create gradations in terms of full or partial citizenship, it did set in place requisites failing which meant not being eligible for citizenship status (to this extent, landless labourers were deemed ineligible). A revision to the act came in 1977 which increased the duration of government services (from five years to now twenty years of service) and period of residence (from 10 years to 15 years) making the whole process difficult and long durée. Additionally, the applicants for citizenship were also required to speak, read and write Dzongkha language which is also spoken by the Drukpa majority i.e. adopt the essence of Driglam Namzha (official code of dressing and etiquettes). They also had to be well versed with the Bhutanese culture, custom and social systems.

The act of 1977 and 1985 further discouraged getting brides from across the border (India and Nepal) by not automatically granting naturalization but by treating the non-Bhutanese wives of Bhutanese nationals as any other foreigner applying for citizenship subjecting them to conditions of residence, employment and sitting through a written exam. The practice of marrying across the border was a convention visibly common among the Lhotshampas. The Marriage Act of 1980 which applied to all marriages post-1977 systematically disempowered an individual who entered such marriages as they stood to lose a lot of benefits that other individuals wouldn’t.

The final legislation of 1985 collapsed all the safeguards associated with the citizenship status of Lhotshampas and triggered a domino effect by 1990s when tens and thousands of Lhotshampas were forced to leave their homes to protect their lives. While the 1977 legislation did not affect the citizenship status of the child born out of wedlock between a Bhutanese and a Non-Bhutanese, the 1985 act voided that provision. Accordingly, a child born out of such a union wasn’t recognized as a natural citizen as only one of the parents was a Bhutanese national. The local power players enjoyed a lot of discretionary power in terms of permitting people to live and work. The adversities associated with the act of 1985 came to light when it began to be enforced in the census of 1988.

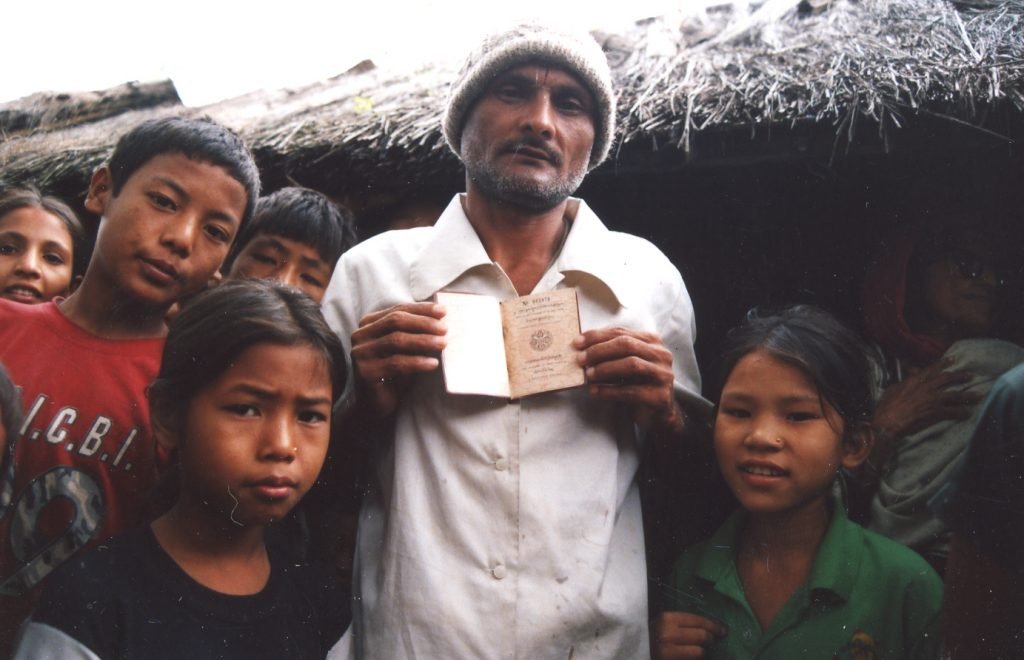

As per the official statements, the census was taken up to identify Bhutanese nationals and provide citizenship identity cards to all “bonafide” citizens. For the Lhotshampas, such an exercise was meant to strip them off their rights granted to them by previous legislation and expel any Nepali ethnic culture from Bhutan. The burden of proof fell on the Lhotshampas which furthered their harassment at the hands of the Drukpa state. A lot of people lost their citizenship and were forced to leave everything. The imposition of civil code- Driglam Namzha was humiliating for the ones who remained in the country and yet were forced to divorce from their sense of being, demoting them to a so-called inferior population. Mandatory civil codes and nationalization of a singular language are seen as acts of submission and are tools of subjugation that the majority class possesses to oppress and silence the practices, cultures and histories of a minority making them invisible.

The Revelations from South Asia

The racially biased and discriminating citizenship law that turned the Lhotshampas into illegal immigrants overnight is not a pattern isolated to Bhutan alone. It is a pattern that has mirrored itself into a conception of state attitude towards its ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, acute to South Asia. Be it the 1971 war of West and East Pakistan (now, Bangladesh) or ethnic crisis of Muhajirs in Pakistan or India during the 80s caught in violence against the Sikh population in Punjab and Delhi. An inherent unacceptability of minorities and their inhumane treatments by the hands of regimes is a story that is lived again and again in South Asia. The spill-over effect in the region has been drastic as well with crisis and conflicts transcending borders. The dissent by the minorities has received disproportional reactions leading to violent clash downs and barbaric lockdowns. The new age has ushered new tools of oppression like blanket bans on commodities, customs and even internet.

Lhotshampas were demoted to second-class citizens in their own country, being treated as outsiders or the enemy other. The enemy other is perceived to be one who enjoys and takes away all that which belongs to the majority and thus needs to be dismissed by whatever means possible. Studies around ethnic conflicts are replete with the majority perception of an exotic other. The Lhotshampas were expunged so that they could supposedly return back to their home. But how does one return to a home that never existed? The enemy other instils a fear of becoming a minority in their own land among the majority that always has a historical proof of their nativity; of them being the original inhabitant. This archetype is true for the Hindu-Muslim relations in India, Buddhist Sinhala- Tamil relations in Sri Lanka and as discussed above the Bhutanese-Nepali relations of Bhutan.

The lives of Lhoshapmpa refugees who continue to live in camps or those who migrated to other continents continue to lead a life marked by trauma and loss. The everyday violence is aggravated particularly for those who live in refugee camps as they grapple with socio-economic inequities and psychological pains. The existential threat continues to exist and lessons to be learnt by the political leadership require moving beyond mere bilateral talks.

As we reminisce the normal and be apprehensive of the new normal that we are heading to, in the wake of the current pandemic, it is very important for us to ask oneself about the vulnerable populations who have no normal to go back to.