Emerging Economies and COVID-19; What’s in Store for Developing Asia

Characterised across the world as informal, cash-based economies with distinctive vulnerabilities, emerging Asia is in high need of a rarity to sustain the future. Pandemics are the mirror of society and hit the vulnerable tremendously. Nations in this region have extremely high populations, limited hospital infrastructure capacities, and acute shortages in medical and essential supplies. Yet, all of these characteristics of this region call for measures that can result in significant economic deprivations along with precarious societal havoc.

The omnipresence of Poverty and hunger further fuelled by the pandemic, make for decreasing business sentiments and plunging economic activity. Coupled with dismal lack of responsibility and global leadership, Covid-19 can be the worst-case scenario that these countries prophesied.

Economic Scars Caused by COVID-19

As India and other Asian countries record the fast spread of the disease, emerging economies move to tightened mobility restrictions which are said to weigh on the already dropping economy. Moreover, a collapse in oil prices resulted in pushed down external and fiscal revenues for emerging oil-exporting nations and a rapid spread of COVID-19 brought about sudden increase in global risk aversion that lifted finance costs of such emerging economies. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is expecting the emerging world to enter a recession of -1 percent in 2020, which could be worse than the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008. Unfortunately, this time around, the stakes are even higher as predicted by Asian Development Bank (ADB), which stated that developing Asia would need to invest $26 trillion between 2016 and 2030, or $1.7 trillion per year, for the region to maintain its growth momentum, eradicate poverty, and respond to climate change. “The Indian economy is predicted to contract 0.9 percent by fiscal year 2021, and Japan officially entered recession for the first time in nearly five years”.

Countries like India, Bangladesh, and Nepal that are highly classified and characterized by their migrating population are in deep trouble owing to strict limitations in mobility and lockdowns imposed as a part of pandemic control measures. This led to a decrease in remittances acquired by these nations by their non-resident working population. The most immediate way for emerging economies to protect themselves from the financing shock is to use domestic policies, both monetary and fiscal. Unfortunately, the room for fiscal policies tends to be limited. Interestingly emerging economies spend too little in the form of fiscal policies to curb the crisis as opposed to their developed counterparts.

On the other hand, there are countries including Lebanon, Syria among others that are on the tip of the iceberg. Crisis in such countries further widens, inducing further hunger, malnutrition, and baffling currency depreciation. Some economies entered this crisis in a vulnerable state with already sluggish growth, high debt levels, and limited fiscal space to support the health sector and the flagging economy. About half of all low-income countries were considered in debt distress or at a high risk of debt distress even before the crisis, as assessed by the IMF’s Debt Sustainability Framework. But not all emerging economies have suffered equally from the same ailments. Some economies are still included in emerging-market indices even though they have mostly emerged: South Korea and Taiwan, for example. These, along with other emerging economies, such as Thailand, that have strong balance sheets, face what might be called “First World problems”: worries over how to maintain employment while managing the public health threat from COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

The good news is that Asia now has a growing number of economically capable middle powers such as Japan, South Korea, and Singapore that can run sustainably, given their economic, financial, and military prowess.

New Window of Growth Opportunities

Countries like Japan and Indonesia are moving towards digital aid to counteract the sudden economic distress caused on Households, Small and Medium enterprises, and to limit the spread intensity of the disease by encouraging cashless payments and online tracking. “ Digital solutions have helped target relief to the vulnerable and enhance the effectiveness of traditional macro policies” according to the IMF.

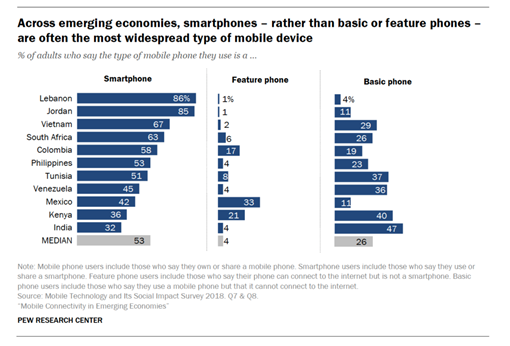

”Since development began late in emerging markets and their infrastructure is limited, the majority of developing countries can be considered ‘mobile-first’. For many people in these countries, their mobile handsets are their sole connection to financial tools, information and other vital services. This means that providing robust fin-tech solutions to such regions is not a matter of convenience, as it is in the first world, but one of necessity, since they bridge gaps for unbanked people”, quotes the World Economic Forum.

The Covid-19 crisis in emerging markets demands a Once-in-a century reform, due to its intensity. Alongside, strong multilateral co-operation and liquidity assistance are significant for countries confronting health crisis. Beyond the pandemic, policymakers must cooperate to resolve trade and technology tensions that endanger an eventual recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.