Seasonal Cotton Slavery In Uzbekistan

Background

Slavery may have been abolished in the 19th century according to its archaic understanding. However, in contemporary times, it has manifested itself in varied and more vicious forms which are embedded in the institutional structures of some countries. Today, 40 million people are estimated to be tricked or forced into modern slavery worldwide. Human rights violations such as dilution of labour rights are gateways to modern slavery. In Asia, the situation is particularly rampant.

Uzbekistan has the 5th largest number of modern slaves associated with its globally infamous cotton production. Cotton, in the whole of central Asia, is regarded as “white gold” as it earns heavy revenue for the governments and the small cluster of elites. Uzbekistan is the largest producer and exporter of Cotton amongst its competitors. The production process has traditionally been labour-intensive. Despite the efforts to mechanise the process, it continues to employ millions of people, especially during the harvest season. During the harvest season, government through its various branches and institution forces the people to pick cotton from farms in return of no compensation.

This has been taken into cognisance by the domestic media as well as international bodies like Human Rights Watch. The government of Uzbekistan responded to activists rallying against the questionable by cracking down on them. Calls to boycott the Uzbek cotton in countries where it is exported have received mixed reaction but does it really help slavery on ground? Many reforms that have been undertaken in desperation for seeking foreign investment, since the death of former President Karimov, have pleased the Western media and officials. There have also been public efforts to reduce forced labour during the cotton harvests. However, many activists are still of the opinion that the applause is coming too quickly.

The structure of slavery and stakeholders

Cotton production is the lifeline of Uzbekistan’s economy. The production is controlled by the state and the producers are required to meet quotas set by the state. The government controls the inputs for cotton production through joint-stock companies which have a monopoly for the input provided by them. The system for making financial transactions is called Selkhozfond. It is housed in the Ministry of Finance, is controlled by high-level officials and does not publicly report income or expenditures. In 2015 the government launched an agricultural “re-optimization” plan to reduce the size of agricultural land allotments and to take over the land of farmers who failed to meet cotton quotas.

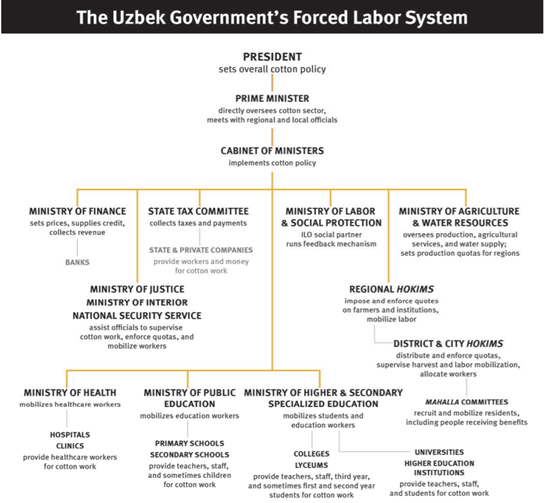

The Prime Minister oversees the implementation of the cotton production plan through heads of various ministries and regional and local bodies. These hierarchical channels are also used to mobilize labour from schools, universities, hospitals, mosques, etc. There are quotas for mobilising labour too on government employees who often resort to threats of expulsion, suspension or trail by the court to force people into cotton picking.

The World Bank has been engaged with Uzbekistan’s agriculture sector since 1995 with Cotton Sub-Sector Improvement Project, which was aimed at liberalizing cotton prices and privatizing the cottonseed industry. The world bank does not acknowledge that child and forced labour is linked to the cotton production in the country, but due to international pressure has taken measure for mitigating the risk of child and forced labour in the sector. The institution has also faced criticism for continuing lending for cotton production although the state still controls it heavily. The response has been that the loans extended were for mechanisation of the production process so that less manual labour is required as slavery-like conditions stem from its heavy dependence on manual work. However, child and forced labour continued on a massive scale even during the 2015-16 cycle, so did the lending.

Human Rights Abuse

Despite having domestic legislation against child labour, free speech and labour rights and signing various international conventions such as the Forced Labour Convention No. 29, Minimum Age Convention No. 138 and Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention No 182. The country has been recklessly committing human rights violations. The Uzbekistan Human Rights Defenders’ Alliance reports that young children as young as 11 were found picking cotton in Andijan, Ferghana and Tashkent regions. Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum documented evidence of forced labour in three additional regions along with evidence linking World Bank-funded cotton production and forced and child labour. School principals must find their own farmers to negotiate with about the harvesting by schoolchildren, as well as take on transportation costs. ILO in its recent report claimed that in 2019 no children were mobilised to work in cotton fields for the first time. This made UK and other countries rethink their plans to boycott Uzbek cotton. However, adult systematic forced labour continues to prevail.

Another human rights violation linked to cotton production is the arbitrary arrests of activists. Under the rule of Islam Karimov, several human rights defenders were put under house arrest and many were detained as political prisoners. In January-February 2008 the government released seven human rights defenders, and another two in October, apparently as a gesture toward the European Union. The authorities prevented the released defenders from meeting with foreign visitors and generally from pursuing their human rights work. Two fled the country, fearing for their safety. The elected leader of the Human Rights Alliance in Uzbekistan, Ms Elena Urlaeva was involuntarily detained in a psychiatric facility and mentally tortured. The purpose of her detention is assumed to be of preventing her from documenting forced labour during the 2016 cotton production cycle.

Since September 2016, authorities have released more than 50 people imprisoned on politically motivated charges, including rights activists, journalists, and opposition activists. However, forced labour in the cotton sector remains widespread. Public sector employees in small towns from across the country still complained of having to pick cotton or pay for someone to do it in their place.

Response by The State

Civil Society groups in both Uzbekistan and other European Nations have requested for the removal of State quotas and ensuring Uzbekistan’s commitments compliance with International Conventions on labour on a global level. Tashkent in response to global pressures has taken steps towards greater liberalisation and market reforms for sustainable rural development post-2016.

In May 2018, Mirziyoev’s government issued a decree aimed at completely ending forced labour. The hope is that the private sector will pay cotton-pickers, instead of simply forcing them into the fields. Anecdotal stories tell of entire farms not having received any type of payment—cash or in-kind—for several years. This is driving local Uzbek peasants cross the border into southern Kyrgyzstan and work illegally, exacerbating border tensions. Privatisation was introduced in the form of “clusters”. ILO recommends phasing out the role of Hokimiats, state institutions and enterprises in production, recruitment and related value chains. The private clusters must start involving social partners and local civil society to maximize social benefits for communities. Clusters, it was hoped, would invest in mechanization and water saving, which would further reduce the burden on manual labour. However, the shift would take time, so the demand for seasonal labour in cotton production and harvesting in the near future will remain high.

In March 2020 the President abolished the quota system for the cultivation and sale of cotton. The system was seen as the root cause of modern slavery in the country. Activists agreed that the move will allow farmers to exercise more agency in the choice of cash crop they can grow.

The Debate on Boycott

There are strong arguments both in favour and against the boycott on Uzbek cotton. On one side are the domestic and international NGOs and Civil Society Groups opposing the lifting the boycott. On the other side are the government officials rallying for lifting the boycott basing their arguments on the ILO (2019) report and reforms took since 2016.

The argument in favour of rolling back the boycott is based on employment and revenue generation, especially in desperate times of a pandemic. The Uzbek government estimates that it can quickly generate much-needed jobs and let the country earn an extra $1 billion this year alone by selling cotton and textiles on Western markets. The export volumes could double year-on-year. The Tashkent government says that nearly 7,000 companies in cotton-related industries employ more than 200,000 workers, whose incomes support 1 million people in the country. An estimated 150,000 people in the country have already lost their jobs. The government is in desperate need of foreign direct investment as it stated to open up its economy after years of tyranny under their former leader.

The Uzbek-German Forum on Human Rights, meanwhile, agreed there’s been progress. However, forced labour continues to be a significant problem for adults, and a network of government agencies, state-owned enterprises, and other informal organizations continues to perpetuate the issue. The international coalition of a rights group called, the Cotton Campaign, had been lobbying endlessly with the government and Multi-national companies said, it was too early to lift a boycott of Uzbek cotton despite Tashkent’s progress in eradicating forced labour and its request to take the global recession into account. Corporate responsibility of 300 brands backing the pledge to boycott has demanded “greater assurance” given their zero-tolerance policies on forced labour. The International Labour Organisation’s finding that more than 100,000 people were in forced labour during Uzbekistan’s 2019 cotton harvest, have left them unconvinced of Tashkent’s proposition.

Cotton Campaign coordinator, Allison Gill has said that Uzbekistan still has a long way to go in empowering civil society, including registering independent nongovernmental organizations and creating space for workers to organize independently. A free and vibrant climate for civil society groups promotes transparency and accountability essential to create responsible investment in the economy.